Turning the Tax System on Its Head: Assessing Syria’s New Fiscal Reform

- Issue 12

In July 2025, Syrian authorities released for consultation a draft law introducing the most consequential tax reform in decades. Expected to enter into force in early 2026, the proposal replaces the fragmented, fee-heavy regime of the war years with a simpler code built on flat rates, high exemptions, and a unified approach to income. It abolishes the schedular system under Law 24 of 2003—separating wages, business profits, and capital income into distinct categories—and instead aggregates all sources of net income under a single framework.

By reforming the tax system, the government seeks to present a model that is unified, simplified, and competitive, echoing the principles that Finance Minister Mohammad Yisr Bernieh emphasized when unveiling the draft. The analysis here draws on the publicly proposed amendments as well as a copy of the draft income tax law obtained by the authors in confidence.

Simplifying Taxes

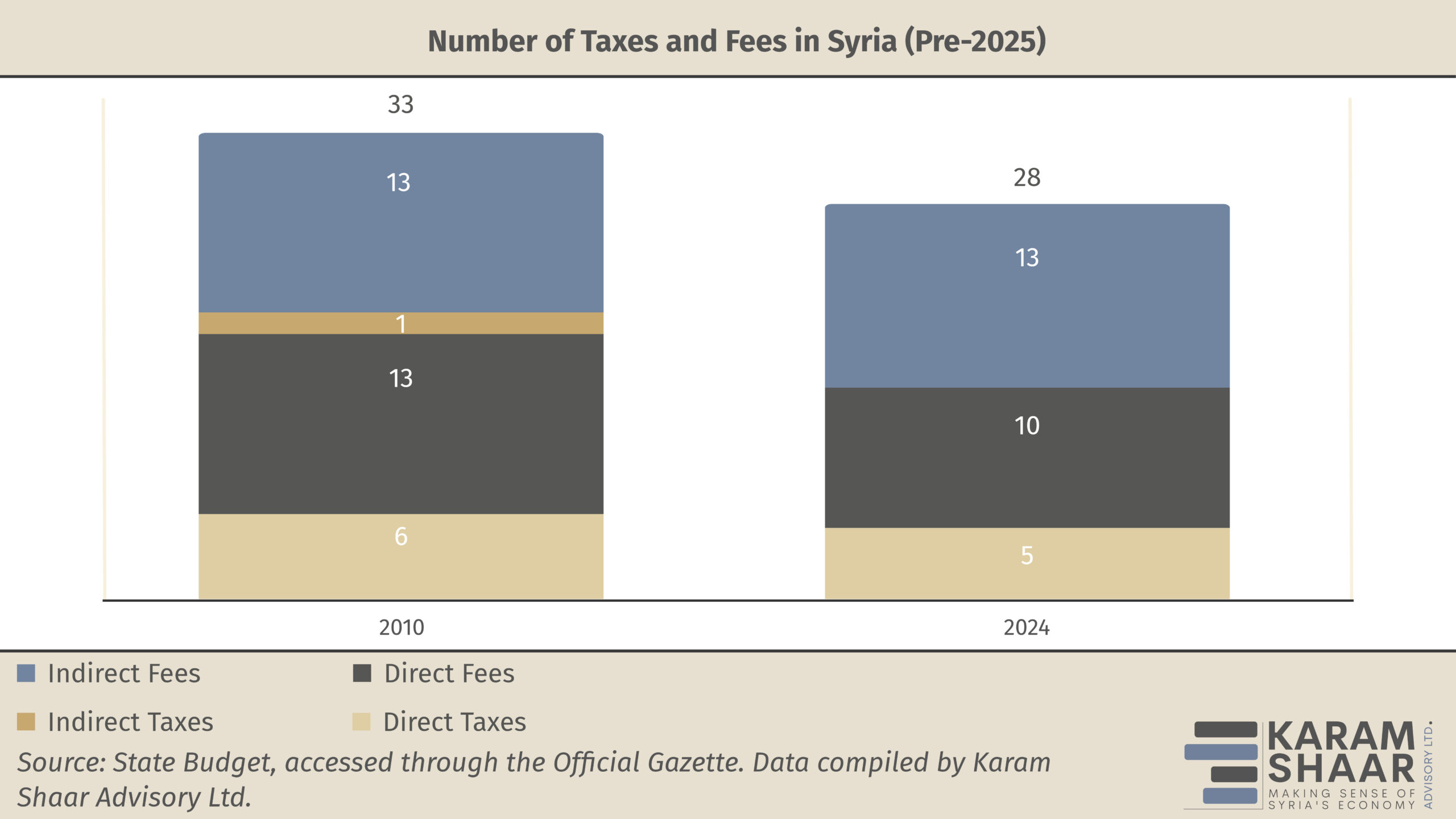

The pre-2025 tax regime was a fragmented, outdated system built on schedular income taxes, arbitrary “lump-sum” assessments, and proliferating wartime fees. By 2024, direct taxes had collapsed to only 11% of expected revenues—while more than half of collections came from regressive indirect levies such as sales taxes, customs duties, and the “reconstruction fee.” The system was widely viewed as opaque, unfair, and excessively reliant on taxing wages and consumption rather than profits or wealth—a theme examined in three earlier analyses of Syria’s taxation system (see Articles 1, 2, and 3).

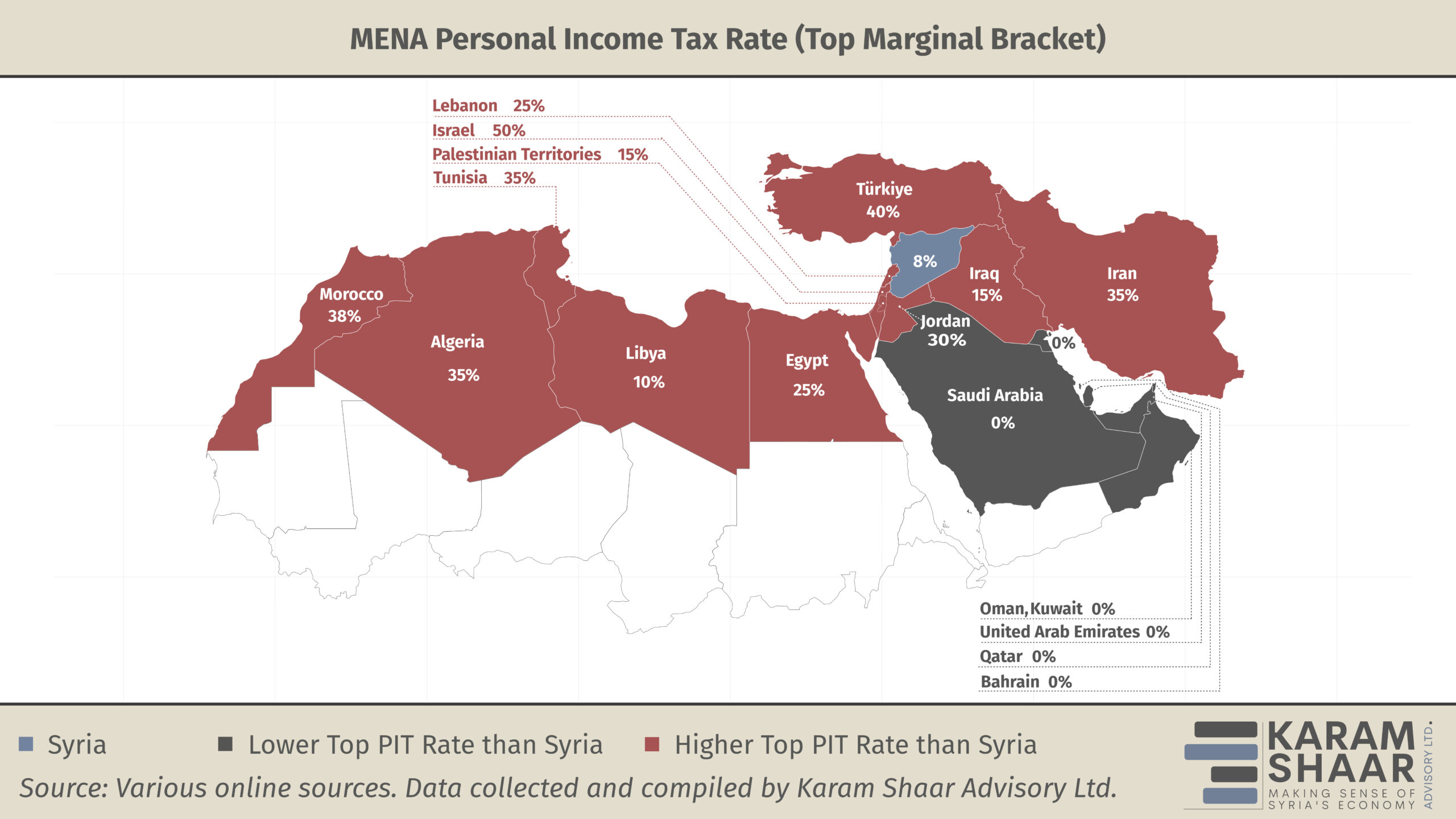

The draft law introduces sweeping changes. For individuals, the personal income tax (PIT) is replaced with a threshold of SYP 60 million per year (about USD 5,200), below which no tax applies. This threshold effectively exempts the 90% of the population living below the poverty line, as well as all workers earning the minimum wage of SYP 750,000 (about USD 65) set in June 2025. Above that threshold, income is taxed at a flat rate of 6% on the first SYP 5 million (USD 435), and 8% on all additional earnings. Such a structure would give Syria the lowest PIT rate in the region among those countries that levy personal income taxes.

In addition to the general allowance, taxpayers may deduct specific expenses: SYP 6 million (about USD 520) for a non-working spouse, SYP 8 million (about USD 695) per dependent child, and documented costs for healthcare, education, housing rent, and loan interest.

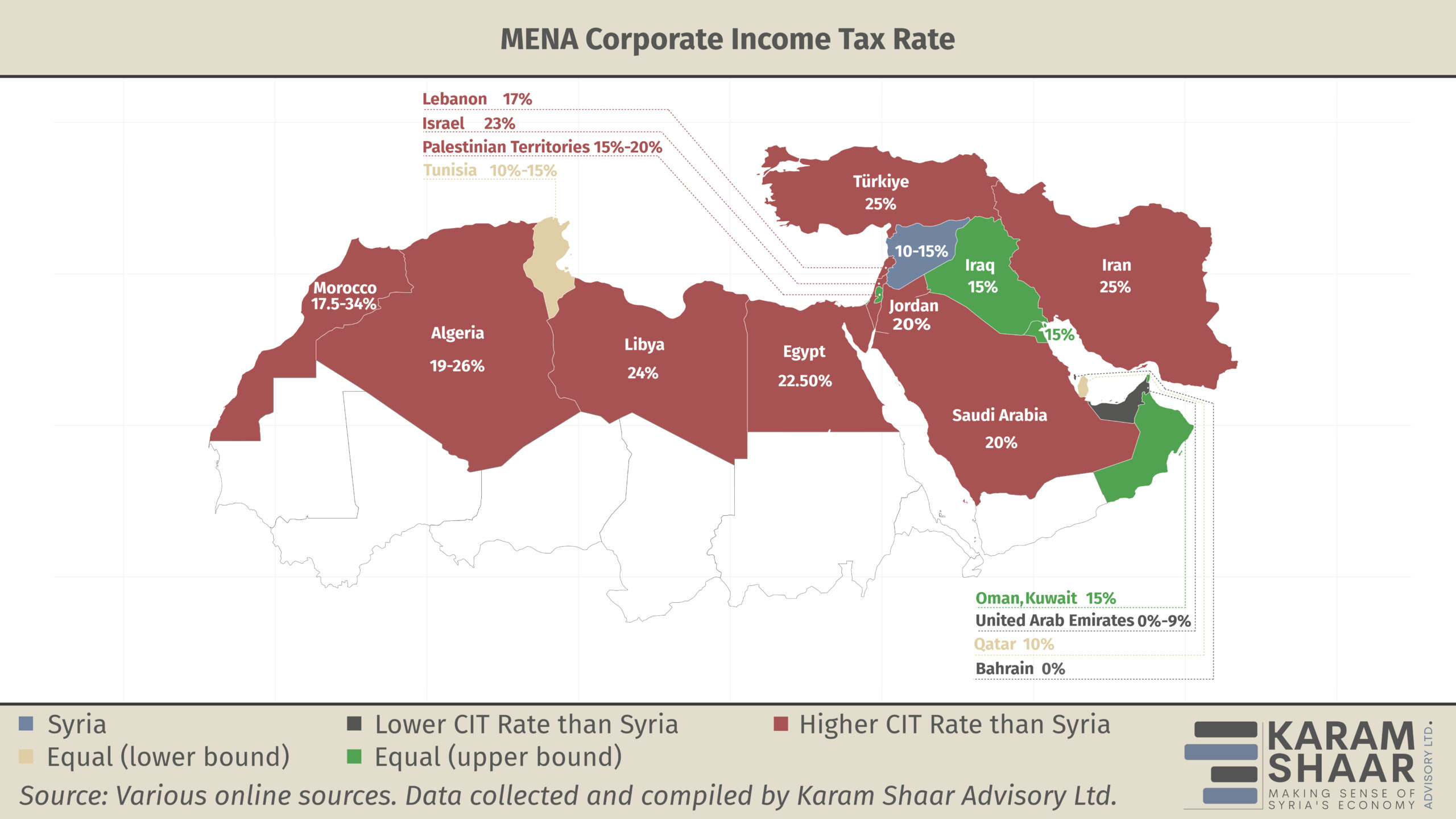

For businesses, the corporate income tax is unified at two flat rates: 10% for priority sectors such as industry, healthcare, education, consulting, technology, training, and aviation, and 15% for all other sectors. Agricultural income remains exempt, in line with long-standing practice. Dividends distributed by resident companies, along with certain categories of foreign investor income, are also exempt. Capital gains are generally taxed at 10%, though real estate transactions remain subject to the separate Real Estate Sales Law.

The law abolishes the discretionary “lump-sum” tax committees that long determined small business liabilities, replacing them with self-declared returns filed either through simplified income statements or full balance sheets depending on firm size. It also consolidates or eliminates many wartime fees—among them the Martyr’s Stamp, War Effort Stamp, and the Reconstruction Levy—which had proliferated since 2011 and fueled perceptions of arbitrary extraction.

On the administrative side, the reform proposes a leap into digitization: e-filing, electronic invoicing, QR-coded receipts, and enhanced compliance units equipped with digital tools. It also establishes specialized tax courts for disputes. While the draft requires the tax authority to justify claims of undeclared income, the burden remains on taxpayers to substantiate their accounts—an arrangement that, if applied fairly, could provide stronger protections than in the past.

Comparison of Current and Proposed 2026 Tax Systems

| Aspect | Previous System | Proposed New System (2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Income Tax (PIT) |

|

|

| Corporate Income Tax (CIT) |

|

|

| Small Businesses |

|

|

| Agriculture |

|

|

| Capital & Investment Income |

|

|

| Fees & Surcharges |

|

|

| Adminis- tration |

|

|

Multiple online references and documents, including a draft tax law reviewed by Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd.

Risks and Limits

The advantages of this model are clear. First, the reform offers immediate relief to households by removing almost all wage earners from the tax base. Given that the vast majority of Syrians live in poverty, exempting low- and middle-income earners from direct taxation addresses both economic hardship and political realities.

Second, by lowering corporate rates to some of the lowest in the region—10 to 15% compared with Lebanon’s 17%, Jordan’s 20%, and Türkiye’s 25%—the reform is explicitly designed to attract capital. Exemptions on dividends and certain categories of foreign investor income might be aiming to lure back diaspora funds and encourage reinvestment in the formal economy.

Third, the simplification and digitization of administration aim to replace the opaque committees and discretionary enforcement of the old system with transparent, rule-based procedures. This offers the prospect of rebuilding public trust in fiscal institutions after years in which taxation was perceived as arbitrary, corrupt, and disconnected from public services. By scrapping multiple overlapping fees and streamlining compliance, the reform also reduces the administrative burden on businesses, which may help encourage formalization and improve the investment climate.

Taken together, these measures are intended to signal that Syria is open for business and serious about fostering private sector-led recovery.

Yet the risks are equally significant. The most obvious is fiscal sustainability. With such a high exemption threshold and such low rates, the PIT will contribute negligible revenue, leaving the government almost entirely reliant on corporate income tax from a small number of formal firms. Syria’s tax-to-GDP ratio—already among the lowest in the world at under 5% in 2024—is likely to fall further under this model. By contrast, tax collection is much higher in non-oil MENA countries such as Tunisia (34%), Jordan (17%), and Egypt (14%), while Türkiye collects around 23% and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average is 34%. The World Bank has argued that 15% of GDP is a tipping point, with countries that reach this percentage tending to see meaningful improvements in inclusive growth.

Even if investment does materialize, a flat 15% on profits will not generate revenues anywhere near the scale required to finance reconstruction costs. The reform assumes that low rates will spur growth and eventually broaden the base, but, at least in the short term, the state risks stark underfunding.

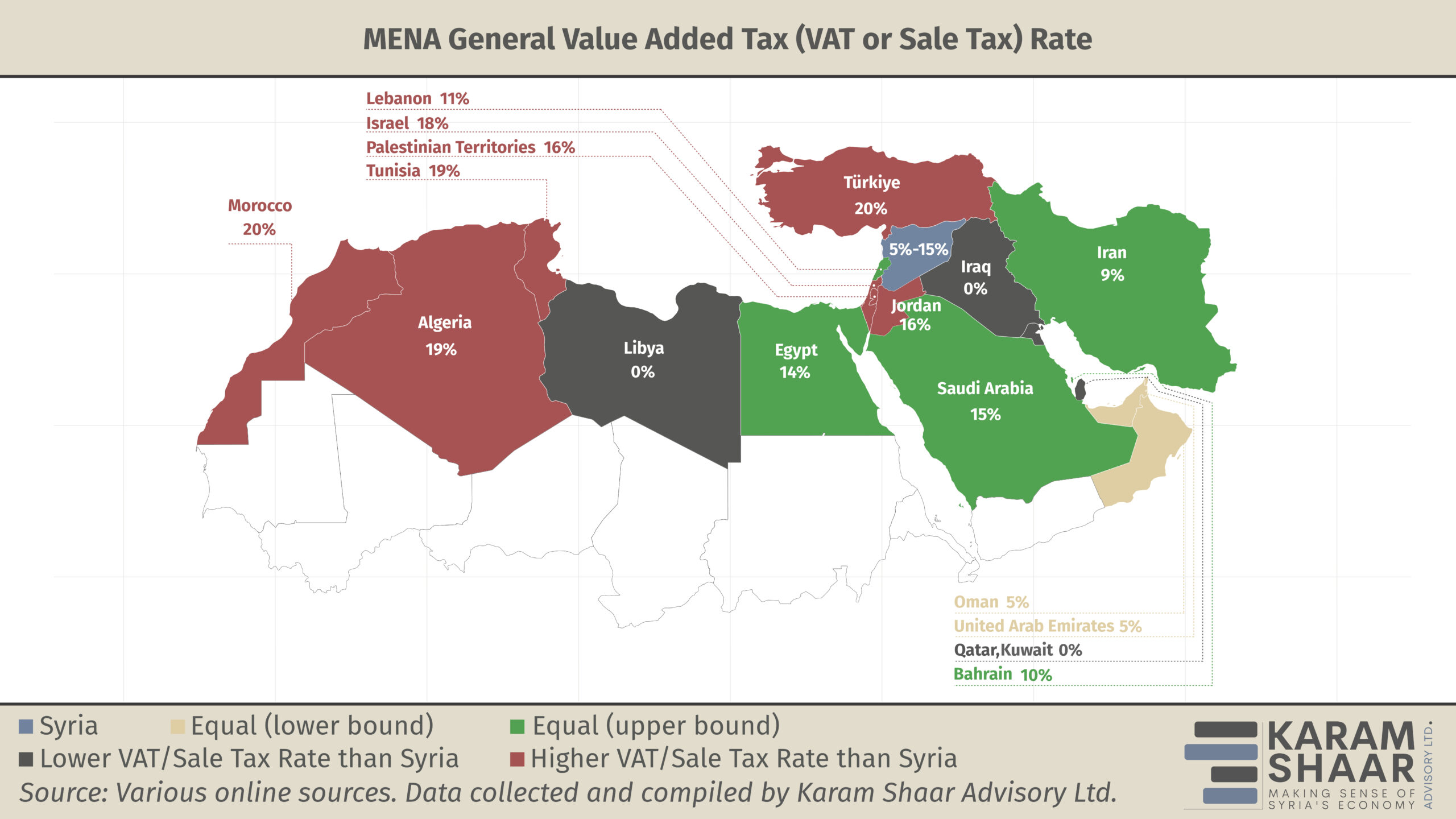

VAT-Like Sales Tax

To try to make up for the limited revenue potential of the new income tax framework, on 23 September 2025 the Ministry of Finance circulated a draft Sales Tax Law that resembles a value-added tax (VAT). The proposal introduces a general rate of 5 percent on most goods and services, with “special taxes” of up to 15 percent on selected luxury items and high-end services. Specific goods are subject to higher sales tax rates, such as pork products and derivatives (45%) and alcoholic beverages (84%). The sales tax will effectively replace the previous consumption tax (Legislative Decree 11 of 2015), which had imposed a fragmented set of excise-style levies on a limited list of goods and services.

The introduction of a VAT-like tax is a positive development in the context of post-conflict recovery. Evidence from fragile states such as Liberia, Malawi, Nepal, and the Solomon Islands shows that introducing or strengthening VAT and customs/excise taxes was central to sustained revenue gains. However, in Syria’s case, the sales tax is not exactly VAT, as it is levied primarily at the final point of sale rather than at each stage of production.

Overall, however, Syria’s redesigned tax system raises further concerns. The exemption threshold of SYP 60 million per year (about USD 5,200) for the income tax appears arbitrary and detached from the country’s actual income distribution, with no clarity on whether or when it will be reviewed. Likewise, the decision to privilege certain priority sectors with a 10% corporate rate while taxing others at 15% is not clearly justified. The criteria appear ad hoc, with little sign of a coherent strategy linking tax policy to national development goals, and uncertainty surrounds the drafting process. It is unclear whether the Ministry of Finance drew on international technical assistance or incorporated lessons from other post-conflict tax reforms, leaving doubts about the reform’s grounding in best practice.

Administrative challenges loom just as large. If the system comes into force in January 2026, officials will have only a few weeks to adapt. Tax staff may lack the training to handle a shift toward self-declaration and digital oversight, creating risks of uneven enforcement and bureaucratic bottlenecks.

At the same time, while digital tools such as e-filing, QR-coded invoices, and electronic invoicing are promising, they presuppose infrastructure that Syria still lacks: electricity supply is unreliable, internet connectivity is scarce, and online penetration remains low (see our interview with the Minister of Telecommunications and Information Technology in the August issue). On the compliance side, households and firms may struggle with an entirely new system, particularly given low levels of financial literacy, entrenched informality, and pervasive mistrust of the authorities.

Given these risks, pressing ahead with the income tax law in its current form would be premature. Instead, the government should open the process to broader consultation, engaging international organizations for technical guidance, the international community for financial and policy support, and—most importantly—Syrians themselves to ensure the system reflects societal and economic preferences. Only through such inclusive dialogue can a tax reform deliver both legitimacy and lasting fiscal sustainability.

The Ministry of Finance did hold a three-week consultation on the income tax law in July 2025, and this appears to have had some impact. The initial proposal set the exemption threshold at USD 12,000 per year, while the latest draft lowered it to SYP 60 million (about USD 5,200)—an adjustment that might reflect the feedback received. Yet the law remains far from meeting Syria’s fiscal and developmental needs, highlighting the shortcomings of a consultation process that was too brief, too narrow, and too limited to deliver meaningful reform.

Similarly, the Ministry of Finance opened a three-week email-based consultation on both the income tax and sales tax drafts.