Despite Assad’s Downfall, Less Than 10% of Syrian Refugees Have Returned

- Issue 10

More than six months after Assad’s fall, only a fraction of Syrian refugees have returned home. Most remain abroad, deterred by the continued lack of housing, basic services, security, and economic opportunities.

The war displaced more than half of the country’s prewar population of 22 million. By the end of 2024, an estimated 7.4 million Syrians were internally displaced, and around 6.1 million had taken refuge in more than 130 countries.

The UN Agency for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated in mid-June 2025 that approximately 577,266 Syrians living abroad had returned since December. This represents less than 10% of the refugee population abroad. Similarly, only about 17% of those displaced inside the country—roughly 1.2 million people—have returned as of May 2025.

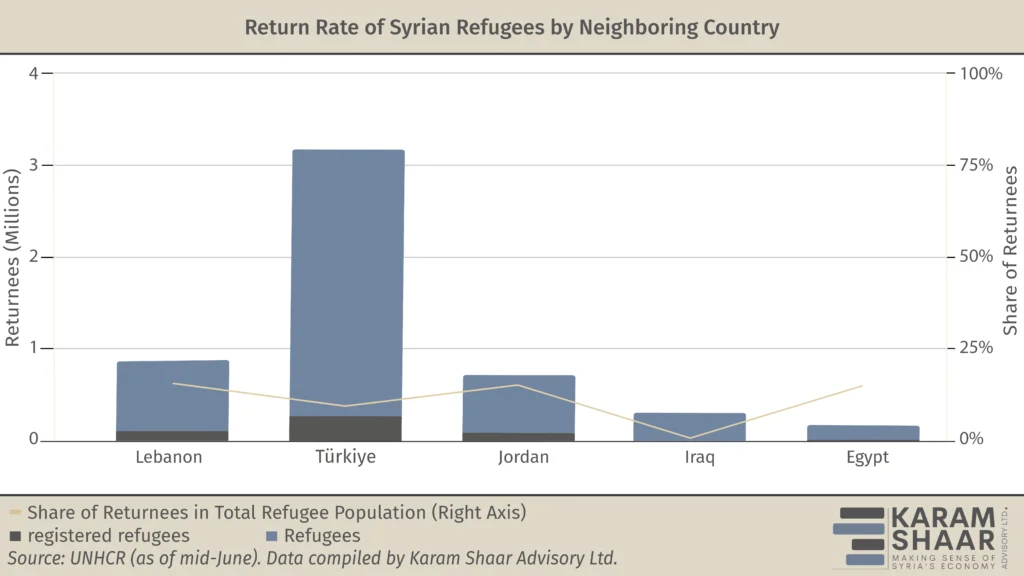

According to UNHCR data from September–November 2024, most refugees initially fled to neighboring countries: Türkiye (2.9 million registered refugees prior to the fall of the regime), Lebanon (0.8 million), Jordan (0.6 million), Iraq (0.3 million), and Egypt (0.1 million). An estimated one million unregistered refugees also reside in Türkiye. In Lebanon, the government estimates the total number of refugees in the country at around 1.5 million.

The definition of “permanent return” varies slightly by host country, and many Syrians now re-enter the country temporarily. As a result, tracking and comparing return patterns is difficult. In Lebanon, UNHCR tracks returns through de-registration figures. Since December, nearly 120,000 have been deregistered. Many others have crossed the border temporarily to check on homes or visit family; these movements are not counted as returns in UNHCR statistics.

UNHCR Egypt noted in mid-June that over 22,200 refugees had requested closure of their case files since December 2024, signaling intent to return. The agency also reported that 16,400 refugees had “spontaneously departed,” though it is unclear whether they left permanently or temporarily.

In Jordan, returns are measured via crossings at the Jaber–Nassib border, UNHCR spokesperson Yousef Taha told Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd. The UN agency estimates 94,000 registered refugees have returned since December.

In Iraq, refugees must formally deregister with UNHCR before returning permanently. Just 2,160 individuals had done so between December and June—fewer than 1% of the total refugee population as of November 2024, according to the UNHCR spokesperson in Iraq, Lilly Carlisle.

In Türkiye, Syrians under temporary protection must apply for return; once approved, their Temporary Protection Identity Document is canceled. Turkish authorities report over 273,000 voluntary returns since December, according to UNHCR spokesperson Selin Unal, interviewed for this publication.

Barriers to return

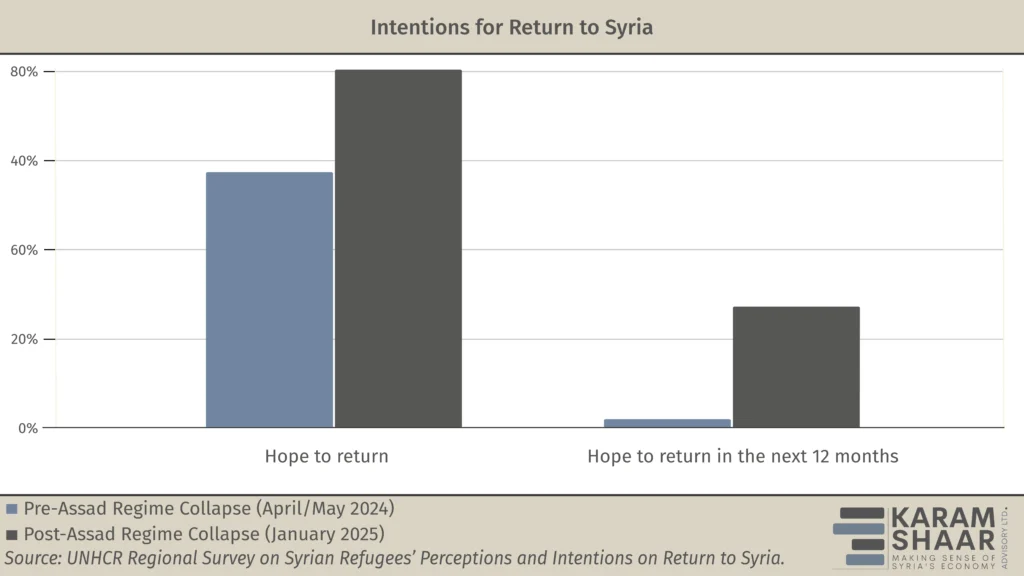

A UNHCR flash survey conducted in January 2025 found that while 80% of refugees in the region hoped to return, only 27% planned to do so within the next 12 months and 53% within five years. Still, this reflects a sharp increase compared to similar surveys conducted under the Assad regime—indicating that Assad himself was a major deterrent. In April and May 2024, only 57% said they hoped to return to Syria, with just 1.7% planning to do so within a year and about 37% within five years.

Based on our calculations, if current return trends continue, roughly 21% of refugees could return by February 2026—nearly reaching the figure cited in the UNHCR report. Another study, launched in February 2025 and published in June, also found that 21% of respondents said they could return within a year.

Intentions vary significantly by host country. In Jordan, Egypt, and Lebanon, 40%, 42%, and 24% of refugees, respectively, said they planned to return within a year—up from just 1% to 2% in the April–May 2024 survey. The most commonly cited obstacle was lack of housing due to destruction, damage, occupation, or disrepair. An estimated 328,000 homes were destroyed during the war, with many more rendered uninhabitable. International funding for reconstruction was limited under Assad, and rebuilding has yet to begin in earnest.

While return intentions rose sharply in most countries, Iraq was an exception. Only 12% of refugees there said they planned to return within a year, up from less than 1% in April 2024. Most Iraqi-based refugees are from northeastern Syria, where fighting between the Kurdish-led SDF and the Türkiye-backed Syrian National Army in January 2025 displaced around 100,000 people, mostly Kurds. Türkiye was not included in the list of surveyed countries.

Other studies echo these findings: insecurity, economic instability, and property loss remain the primary deterrents to return. Some surveys also point to increasing sectarian polarization. Sunni respondents were more likely to report improved security, while minorities generally expressed greater fear and distrust toward interim authorities.

Another disincentive could be the loss of refugee status upon permanent return—particularly for those with jobs or families abroad. UNHCR Regional Spokesperson Tarik Argaz told Karam Shaar Advisory that refugees who approach UNHCR and express their intention to re-establish themselves permanently in Syria are thoroughly counselled that this re-establishment will lead to cessation of their refugee status. Their refugee record is closed once they voluntarily return.

UNHCR’s regional clarification on this point is important, as many returns happen outside official channels. For those “spontaneously returning” (leaving unofficially), UNHCR does not close a refugee record until it is established that the refugee has remained outside the country of asylum for an extended period of time, and it is confirmed they have re-established themselves in Syria and found a “durable solution,” Argaz added.

To address this, Türkiye launched a “Go-and-See” program, allowing 27,000 to visit temporarily and return to Türkiye afterward, UNHCR spokesperson Selin Unal told Karam Shaar Advisory.

Other countries are also initiating return programs. In early June, Lebanon finalized a plan to repatriate 400,000, offering a USD 100 per-person incentive. As of late June, the program had not yet launched but was expected to “start shortly,” UNHCR communications assistant Theresa Fraiha confirmed.

In neighboring Cyprus, which hosts a large number of refugees relative to its population, authorities are offering airline tickets to Jordan, bus fare to Syria, and over EUR 1,000 in cash per family under its Assisted Voluntary Return Programme.

Yet these incentives carry limited weight against Syria’s economic conditions. In April, the World Food Programme (WFP) estimated that a family of five needed SYP 2,190,381 per month (about USD 200, based on the average black market exchange rate at the time) to meet basic needs. Rents are soaring: as of February, a middle-class apartment in Damascus cost SYP 4 to 5 million per month (USD 400 to 500).

Moving in the opposite direction

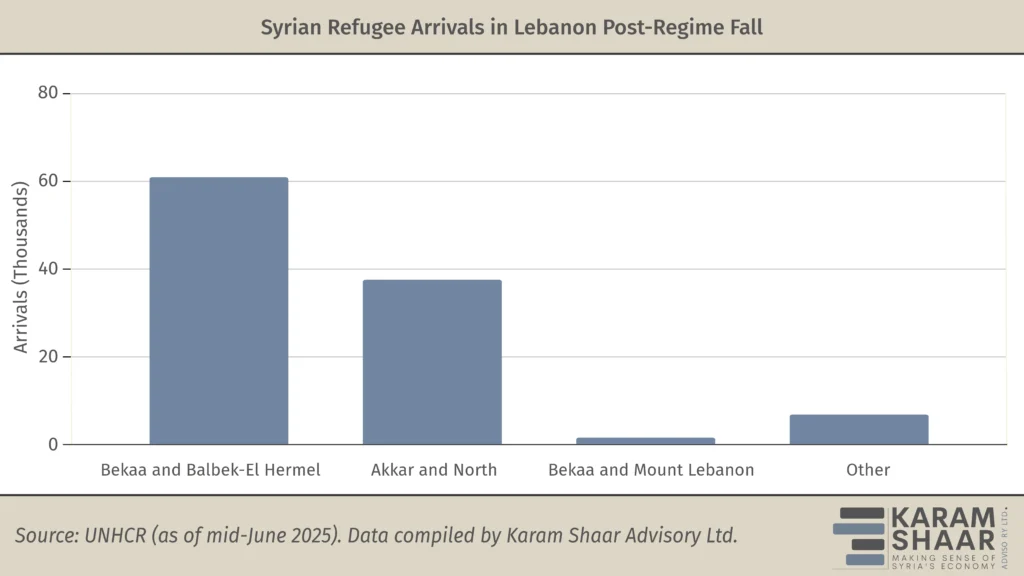

Despite the overall trend toward return, thousands have left the country since Assad’s fall. Lebanon has received the largest share, with 106,754 entering since December. According to UNHCR, around 37,450 were fleeing the sectarian violence erupting in early March in coastal areas, Hama, and Homs. Among these new arrivals, only half were considering returning in the foreseeable future, and none reported feeling that return was safe.

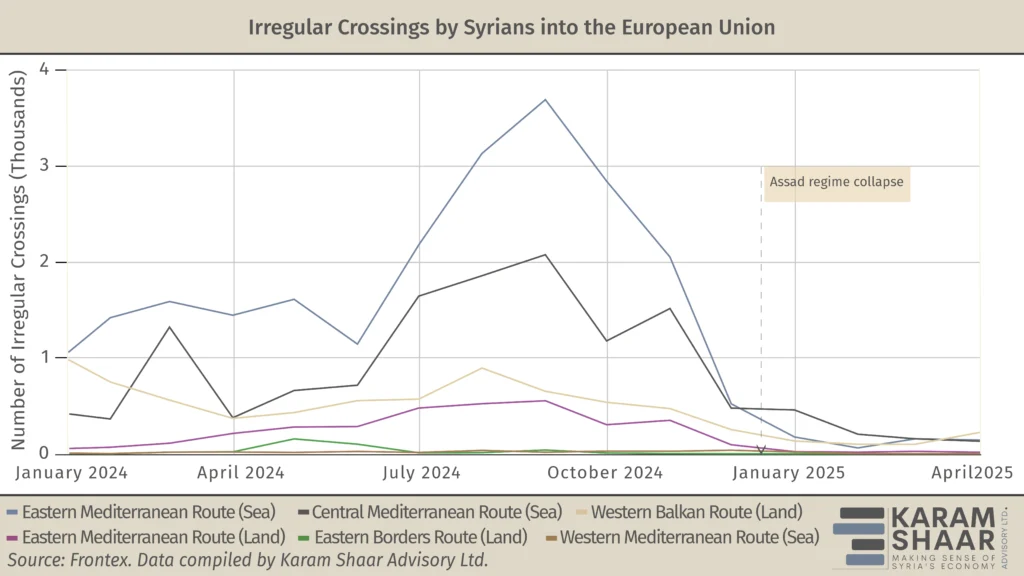

In Iraq, 1,236 refugees and asylum seekers arrived between January and June 2025—a 50% drop from 2024, UNHCR-Iraq spokesperson Lilly Carlisle told Karam Shaar Advisory. Cyprus received 369 new arrivals over the same period. Although overall numbers have declined, hundreds are still attempting the dangerous sea journey to Europe—many driven by worsening conditions in host countries and with no plans to return home.