Rethinking Subsidies in the Post-Assad Era

- Issue 10

For decades, Syria’s subsidy system functioned as a key instrument to support the poor and improve development indicators. While the government began scaling back subsidies as early as 2007, citing inefficiency and corruption, this shift had unintended consequences. In particular, the easing of fuel subsidies—and its impact on agricultural inputs—was viewed by some analysts as a contributing factor to the unrest in 2011.

As the conflict escalated, growing pressure on state finances forced further real (inflation-adjusted) reductions in on- and off-budget subsidies. The government implemented subsidies by lowering the prices of goods and services provided by state-owned enterprises, especially in sectors such as electricity. It also imposed price controls on essential consumer goods sold by the private sector, allowing only set profit margins.

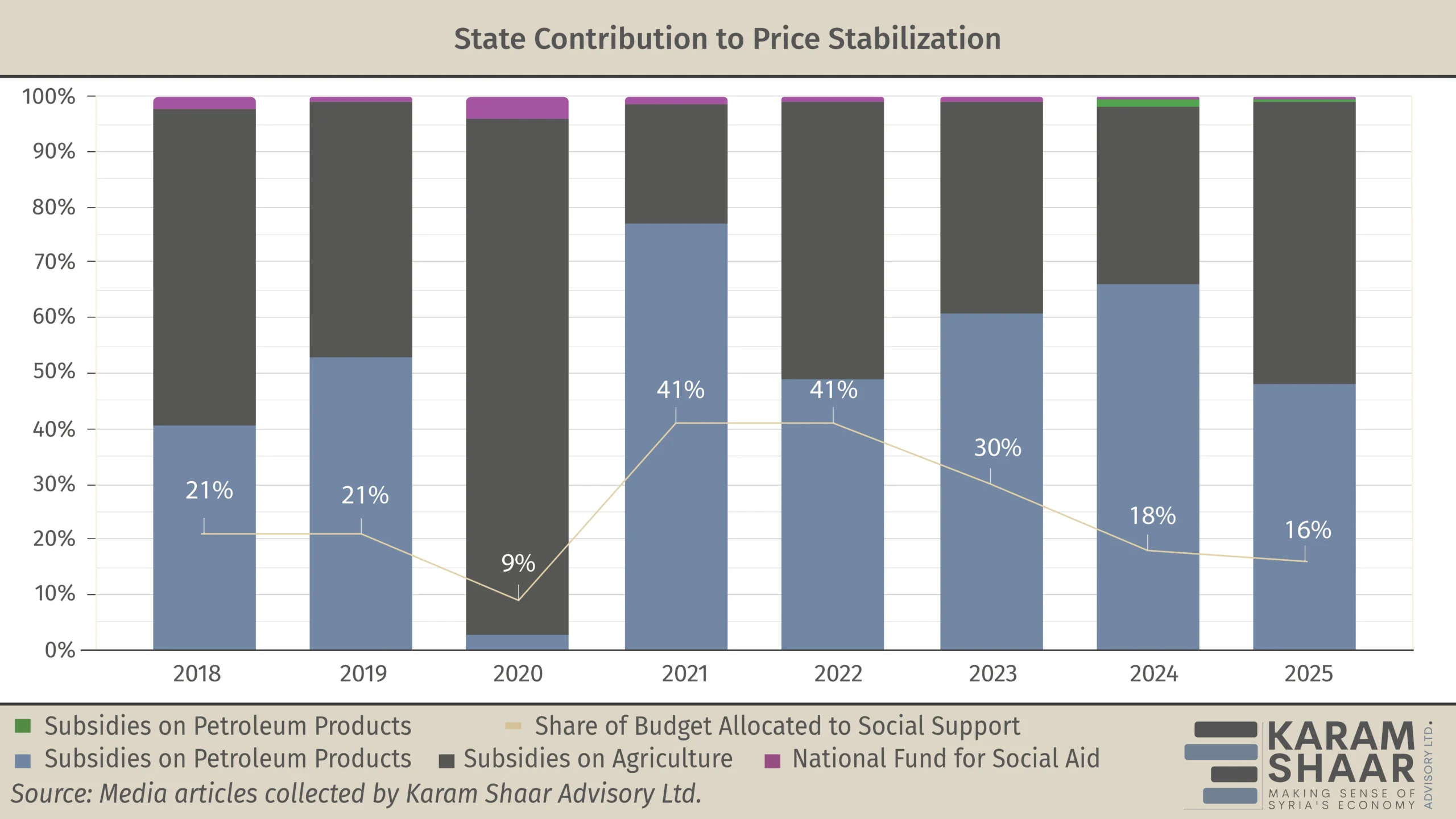

Since the beginning of the conflict, the subsidy system has at times consumed up to 40% of government spending. As the war progressed, economic collapse rendered this model unsustainable. In response, authorities introduced subsidy cuts and a shift toward coupon cards to better target recipients—while also initiating discussions about moving to cash transfers. However, these reforms were poorly communicated, excluded many eligible beneficiaries, created opportunities for corruption, and remained only partially implemented.

To Lift or Not to Lift Subsidies?

As of 8 December 2024, only bread, fuel, public transport, housing gas, and electricity continued to receive subsidies. After the Assad regime’s sudden collapse, the remaining elements of the subsidy system began to be dismantled.

After transitional authorities removed the bread subsidy earlier this year, the World Food Programme (WFP) launched a targeted initiative to subsidize bread at cost price in coordination with the government. The program, still ongoing, covers five governorates—Daraa, Tartous, Aleppo, Hama, and Homs—identified as among the most vulnerable. It aims to reach around 2 million people with 40,000 tonnes of flour through the end of 2025. In areas not yet included, such as Damascus, households continue to buy bread at market prices, which rose to ten times the previous subsidized rate. Expansion of the initiative is under consideration.

In January 2025, the caretaker Ministry of Transport declared that fuel subsidies for public transportation would be eliminated, and a study was reportedly underway to determine new fare structures. The full liberalization of diesel and gasoline prices followed in March, affecting public transport nationwide. Despite sharp increases in transport fees, a notable improvement was observed in service availability, which had previously been constrained by the combined effects of fuel shortages and price controls.

By July 2025, most petrol and diesel subsidies for Smart Card holders were lifted. In 2024, fuel subsidies—including cooking gas—accounted for two-thirds of the total amount allocated to the State Contribution to Price Stabilization, according to budget figures. In the first week of July 2025, a liter of gasoline (Octane 95) was sold at USD 1.11, compared to USD 0.89 in neighboring Lebanon, which also does not subsidize petroleum derivatives. Gasoil—a common regional term for diesel fuel—was sold in Syria for USD 0.96 per liter, compared to USD 0.86 in Lebanon.

The slight difference between the neighboring countries can be attributed to the ongoing disruption and fragmentation of supply chains to Syria, in part due to the absence of shipments from Iran following Assad’s downfall.

In July 2025, the Syrian Company for the Storage and Distribution of Petroleum Products (Mahroukat) also announced the end of subsidies for cooking gas, once among the most heavily subsidized household commodities. From the collapse of the regime until the announcement in early July 2025, the subsidized supply faced disruptions but remained in place under a limited scheme. During this time, the price of canisters sold via the Smart Card stood at about USD 2 but is now expected to rise to USD 11.80, as set by the exclusive supplier, Mahroukat.

Although not listed in the state budget due to its interdepartmental supply chain, electricity is now the government’s main subsidy expense—even though the state supplies only a few hours of electricity per day. There too, the Minister of Electricity announced in January 2025 that subsidies would be gradually reduced or potentially eliminated. He acknowledged that current electricity prices are “far below actual costs.” The phasing out of subsidies in this sector has been under discussion since the final years of the Assad regime, particularly as reconstruction advanced and price adjustments became more frequent.

While continuing broad-based subsidies like electricity without predictable funding is both wasteful and unsustainable, abrupt removal without providing alternatives to vulnerable populations could spark social unrest. To offset recent cuts, the government enacted a modest 200% increase in public sector salaries in June.

More broadly, the subsidy system requires urgent reform to become better targeted, more efficient, and less vulnerable to corruption—especially given limited state resources. In most developed countries, this has meant moving away from non-targeted price subsidies, especially in sectors like electricity, and toward direct cash transfers.

Part of the solution lies with the Interim Government, which has so far favored highly liberal economic policies but provided little detail on its social welfare plans. Removing subsidies without a functioning cash transfer system should not be an option. Doing so risks triggering unrest and deepening poverty. As such systems typically take years to establish due to their inter-agency nature, any easing of subsidies must be gradual and, wherever possible, coordinated with relief organizations.