Freezing Bank Deposits Gives Rise to a Parallel Market

- Issue 12

After fourteen years of conflict and crippling international sanctions, Syria’s banking and financial sectors are on the brink. The fall of the Assad regime has not yet brought relief; instead, it has exposed new layers of fragility.

In February 2025, the Central Bank of Syria (CBS) imposed strict limits on cash withdrawals. Customers could take out only SYP 200,000 (around USD 20) per transaction per week, a limit raised to SYP 600,000 (around USD 60) in early August. On 14 August, the Commercial Bank of Syria (CBoS) also raised the daily withdrawal ceiling at in-branch POS machines to SYP 1 million (around USD 100.4). These measures effectively froze deposits, leaving families unable to meet daily needs and businesses unable to cover operating costs—even as banks continued to show substantial cash holdings on paper.

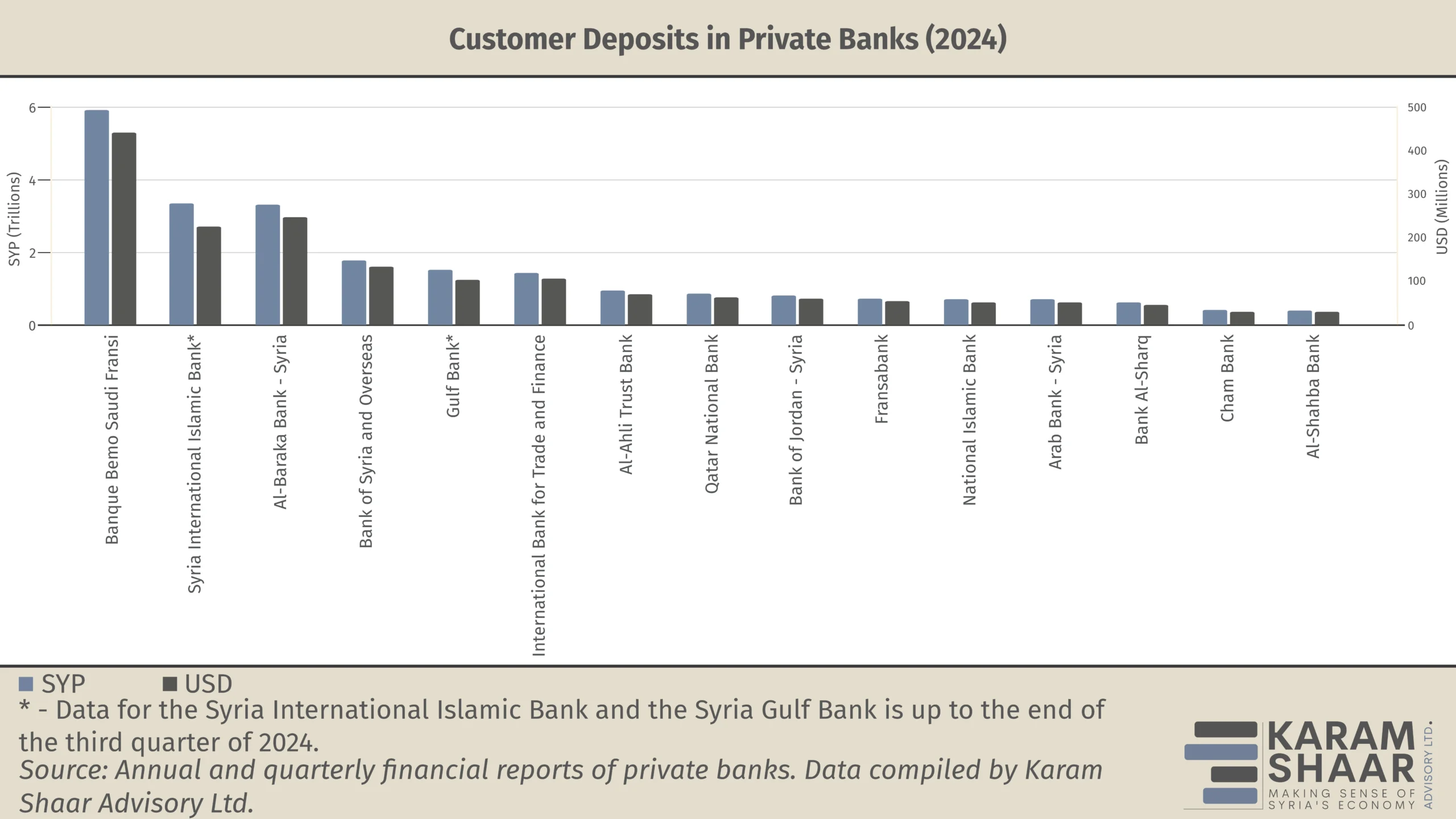

By the end of 2024, customer deposits in private banks (in SYP and their foreign-currency equivalent) stood at SYP 23.5 trillion (USD 1.7 billion), based on annual financial reports reviewed by the authors. For public banks, the latest data from the Central Bureau of Statistics show that customer deposits at the CBoS reached SYP 2.6 trillion (USD 151.5 million) at the end of 2022, compared with SYP 5.6 trillion (USD 326.5 million) for private banks in the same year.

Yet most of this money sits with the CBS, which withholds liquidity from commercial banks—rendering deposits inaccessible. The CBS never clarified its reasons, leaving these funds effectively frozen. In bilateral discussions with the authors, Syrian authorities and bankers acknowledged that the CBS did not have enough liquidity in its vaults to meet demand. In a recent interview, Central Bank Governor AbdulKader Husrieh mentioned the “lack of domestic liquidity” as a significant challenge facing the economy today.

Whatever the motive, the restrictions created what became known as the “bank balance market,” where desperate depositors sell semi-frozen balances at steep discounts to traders with liquidity, who then profit by securing exemptions or withdrawing funds gradually. Such secondary markets for deposits are not unique to Syria. They have appeared in several crisis-hit economies where banks impose withdrawal limits, giving rise to the phenomenon of deposit “haircuts.”

For instance, in Lebanon during the 2019 financial crisis, the “Lebanese dollar” or “lollar” emerged after banks imposed de facto capital controls. Depositors were forced to either leave their funds trapped in accounts or to withdraw them at deeply discounted rates, far below the market rate. Similarly, Argentina in 2001–2002 imposed the “corralito,” forcibly converting USD deposits into pesos at 1.4 ARS/USD while the black-market rate neared 4 ARS/USD. Households and firms were forced to take heavy losses to access their own cash.

Losing Money to Do Business

The inner workings of the deposit haircut system are better explained by the individuals who partake in it, such as with the case of Abu Mohammad al-Homsi, a well-known ink trader in Damascus.

Abu Mohammad explained to the authors that most government institutions upgraded their printers at the beginning of 2025, leaving his warehouse stocks of ink for older models nearly worthless. To continue doing business, he urgently needed to import modern stock. Finances were not the problem: his bank account held a balance of SYP 700 million (about USD 70,000 at the time). The problem was that this sum was locked behind withdrawal limits that let him access only a fraction each month.

“I had money on paper, but I couldn’t move it in reality,” he recalls. “The market doesn’t wait; opportunities vanish if you don’t act quickly.”

Faced with losing his clients, Abu Mohammad turned to what has become a common solution among traders: selling his bank balance at a discount. After negotiations, he agreed to a 25% haircut. Out of SYP 700 million, he received SYP 525 million (USD 52,500) in cash, sacrificing SYP 175 million (USD 17,500). Painful as the loss was, it allowed him to immediately import the ink he needed and preserve his business relationships.

Abu Karim, a Damascene businessman in the trading of granite, reveals why this market thrives. For him, frozen balances are not a burden but a lucrative investment. “Every balance I purchase provides me with returns I can’t get elsewhere,” he explained. In one case, he paid a depositor SYP 208 million (USD 20,800 at the time) for a frozen balance of SYP 260 million (USD 26,000). He then reportedly secured an exemption from the CBS by paying a 5% fee of SYP 13 million (USD 1,300). Abu Karim declined to comment on how he obtained the exemption, and we could not corroborate this claim with other sources. Once the full amount was released, his net profit reached SYP 39 million (USD 3,900)—an 18% return.

Abu Mohammad and Abu Karim’s stories are far from unique. Across the country, households and small businesses with urgent cash requirements are forced to sell deposits at heavy discounts. This deepens inequality between those who can absorb losses and those who cannot, and entrenches public mistrust in banks. Private bankers in Damascus told the authors that frozen balances and the liquidity crunch are choking consumption, trade, and recovery across the economy, and are already reshaping public perceptions of the banking sector.

Moreover, the burden is felt unevenly: under current CBS rules, only deposits made after 7 May 2025 can be withdrawn freely. Long-time residents with older savings are penalized, while returnees or those who brought in fresh capital enjoy privileged access to liquidity and new opportunities. This arrangement does provide the system with some fresh liquidity and partial relief, but it remains deeply unfair to older depositors. What began as a temporary liquidity measure risks hardening into a lasting source of grievance and social tension.

In search of alternatives, Syrians could turn to Sham Cash, an e-wallet mandated by the Ministry of Finance to disburse public-sector wages. Despite operating without clear regulatory licensing, it has expanded significantly since the fall of the Assad regime.

Yet while it offers easy, unlimited withdrawals through hawala agents like Al-Fouad and Al-Haram, the platform is fraught with risks: it operates outside official mobile app stores, lacks regulatory oversight, harvests sensitive data without safeguards, and bypasses the formal banking system—transforming a tool designed for inclusion into a potential instrument of surveillance and abuse. Without proper oversight, Sham Cash gives operators the power to monitor transactions, track the locations and spending patterns of users, freeze or selectively block accounts, and potentially weaponize access by rewarding allies and punishing opponents.

The Need for International Support

With deposits frozen, trust in banks eroding, and Syrians facing unequal access to funds, this poses a threat to the country’s fragile economic recovery. For external partners, several areas of engagement stand out.

Decisions on restoring equal treatment of deposits and easing withdrawal limits lie with the CBS and transitional authorities. External partners, however, can play a role by ensuring that financial assistance is linked to progress on equitable access, while offering unconditional technical cooperation to strengthen institutions and share lessons from other post-conflict economies.

The Deposit Insurance Authority, created in August 2025, offers a direct entry point for support. Its credibility depends on actuarial expertise, reserves, and governance—areas where donors can contribute seed funding, guarantees, training, and technical systems.

Trust will also hinge on transparency and safer digital payments. While publishing liquidity data remains the authorities’ decision, partners can support by supplying reporting tools, capacity-building, and piloting regulated payment platforms with mobile operators and fintechs. These would offer secure alternatives to opaque e-wallets like Sham Cash.