From Deflation to Uncertainty

- Issue 14

In our April edition of Syria in Figures, we noted that the economy had entered a rare phase of deflation after years of a double whammy: money printing during an economic contraction, which repeatedly pushed inflation into triple digits under the Assad government. We highlighted how the abrupt collapse of the old order—combined with the adjustment of import duties, the dismantling of internal trade barriers, a liquidity squeeze, and improved sentiment driven in part by the easing of Western sanctions—had produced a period of falling domestic prices in Syrian pounds (SYP) and an appreciation of the currency that reduced import costs. We also cautioned that the decline in prices was fragile, driven largely by one-off shocks rather than any genuine improvement in economic fundamentals, such as the balance of payments or the fiscal position.

Six months later, those warnings appear prescient.

Looking at Prices

Tracking inflation in Syria has become increasingly difficult over the past six months, as the Central Bank of Syria has inexplicably stopped publishing monthly consumer price data. The most recent figures from February 2025 showed a period of sharp deflation: year-on-year it stood at 15.2 percent, compared to inflation of 109.5 percent in February 2024, while prices fell 8.0 percent month-on-month after a 9.3 percent drop in January. Since then, the Central Bank has released no further updates, leaving a significant knowledge gap on one of the economy’s most important indicators.

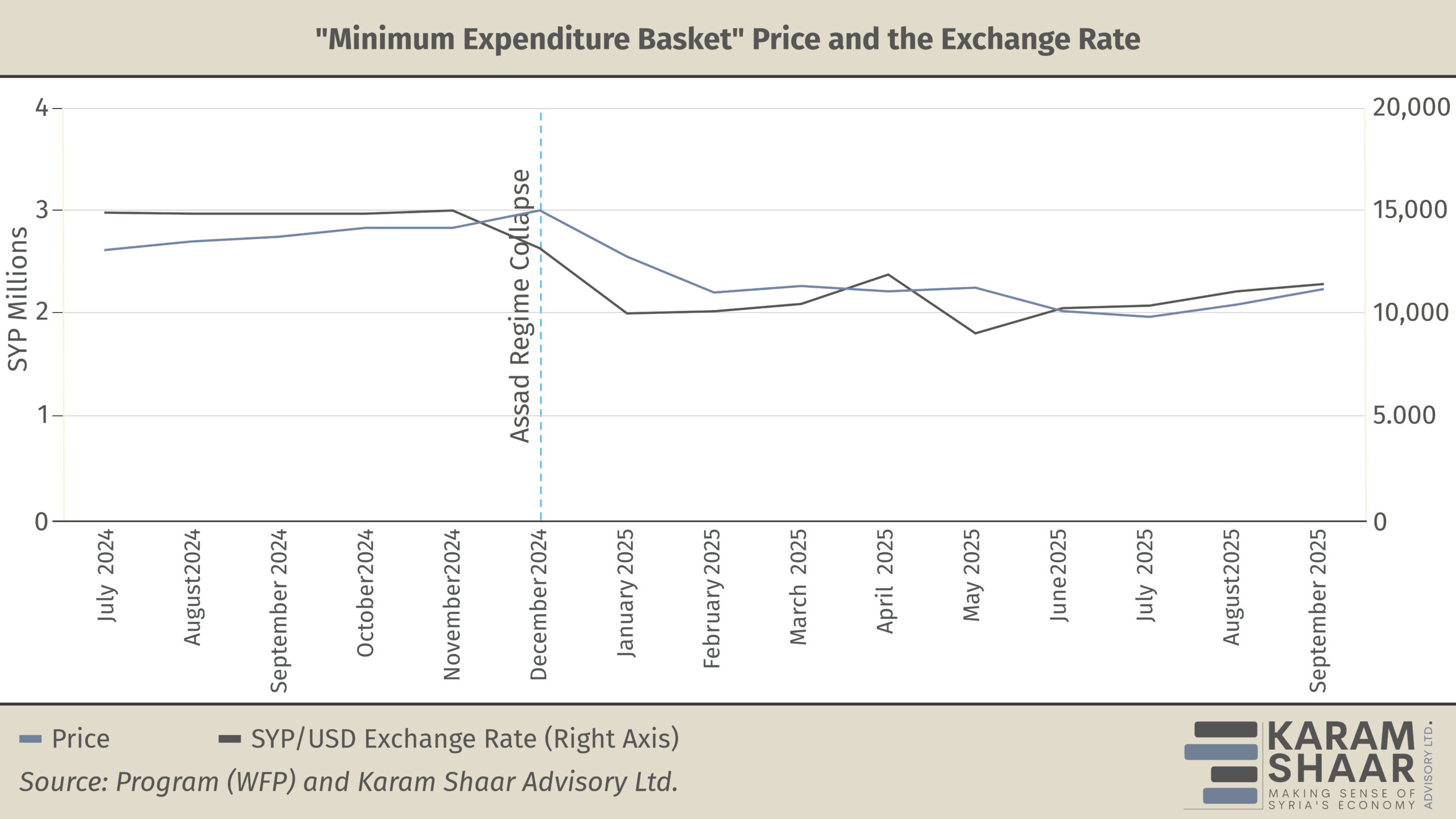

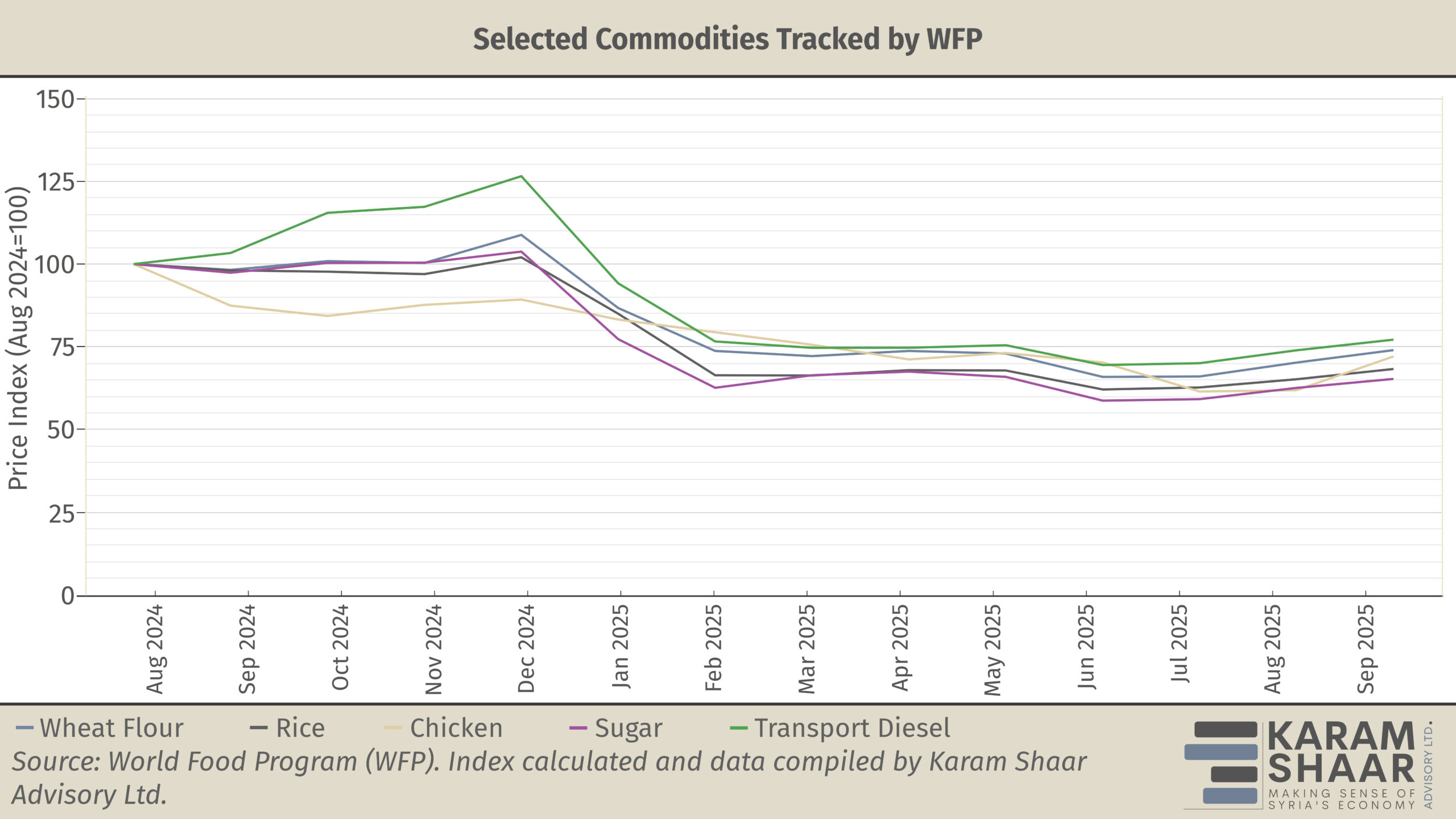

In the absence of official data, new estimates from the World Food Programme (WFP) offer a clearer view of recent price movements. WFP figures show that the Minimum Expenditure Basket (MEB)—a proxy for the average household’s cost of living—rose in August 2025, the first month-on-month increase since the start of the year, with signs the trend continued in September. After falling from 3.0 million SYP in December 2024 to 1.9 million SYP in July, the national MEB increased six percent to 2.0 million SYP in August and then seven percent to 2.2 million SYP in September. This pattern suggests the deflationary phase may have bottomed out. According to WFP, the increase was driven by higher prices for potatoes, vegetables, eggs, and vegetable oil, reflecting tighter seasonal supply amid widespread drought and a weaker exchange rate.

While most MEB components are locally produced and shaped primarily by domestic conditions, many still rely indirectly on imported inputs—such as fuel and fertilizers—meaning exchange rate movements continue to exert delayed pressure on local prices. The dollar value is also crucial for Syrians dependent on remittances, whose real purchasing power has weakened as the SYP strengthened, reducing the local value of foreign-currency transfers.

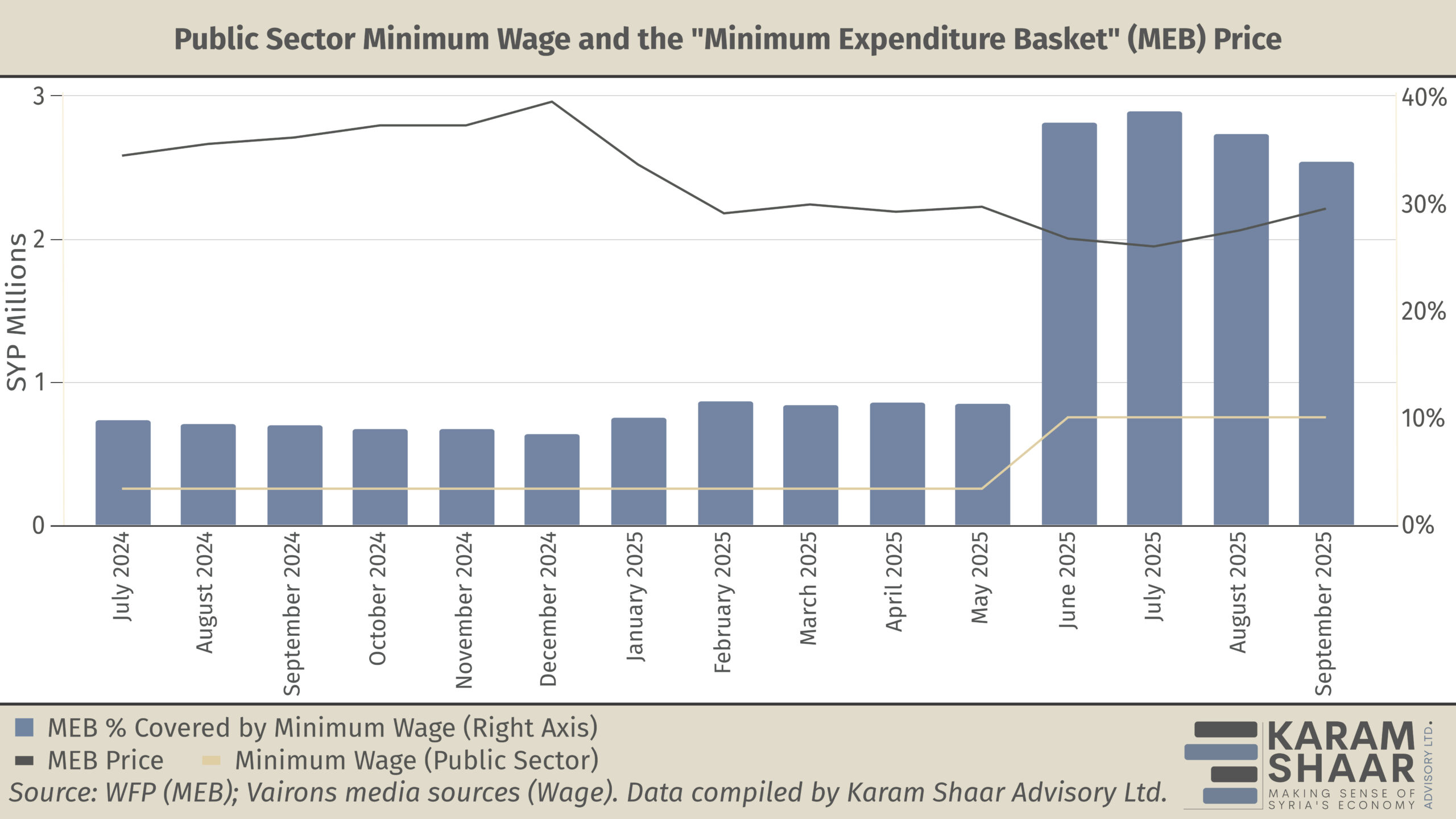

The combined effect of earlier declines in MEB costs and the June 2025 wage increases has modestly improved real purchasing power, though households remain severely constrained. By September 2025, the public-sector minimum wage of SYP 750,000 covered roughly 34 percent of the MEB, up from just 10 percent before the pay rise.

Upward Pressure on Inflation?

September data suggests that the deflationary phase may have passed. Beneath the surface, several dynamics—from rising wages and subsidy cuts to potential budget pressures and a gradual rebound in domestic demand linked to the return of one million Syrian refugees—may now be widening the gap between demand and available supply. For the moment, Syria’s wage increases have not translated into significant inflationary pressure, largely because they were introduced during a severe cash crunch. If that crisis eases and households resume deferred consumption, demand could start to outpace constrained domestic production and push prices higher. Any increase in government spending or renewed money printing would add further pressure.

The appreciation of the SYP, one of the main drivers of lower import prices, remains fragile. Its stability seems to depend more on liquidity restrictions and market confidence than on structural improvements in economic conditions. If the Central Bank loosens its controls, foreign inflows weaken, or the broader recovery slows, renewed depreciation could quickly reverse recent price gains.

Compounding this risk is the government’s fiscal position: officials have stated that Damascus will not resort to borrowing or deficit spending (printing money), raising questions about how future salary payments and essential imports will be financed. As we noted in a previous issue of Syria in Figures, budget pressures are likely to persist under the proposed tax reform, which is expected to generate only limited revenue.

Looking ahead, additional factors are also likely to add upward pressure as the economy gradually reopens. The return of tourists, diaspora visitors, and new investors will boost demand in urban and coastal areas, often beyond existing supply and infrastructure. Rents have already risen across several parts of the country. At the same time, the continued phase-out of subsidies, now targeting electricity, will increase production and transport costs and amplify cost-push inflation. Meanwhile, the 2025 drought—one of the worst in decades—has slashed domestic cereal production to an estimated 900,000 tonnes (metric; ≈990,000 US tons) of wheat, while needs stand at about 2.55 million tonnes, forcing greater reliance on imports that, if unmet, could drive prices even higher.

In this context, the absence of comprehensive and timely inflation data is particularly concerning. Beyond food prices, there is an urgent need for transparent, regular publication of consumer prices, fiscal, and monetary indicators to inform evidence-based policymaking. Without reliable data, Syria’s authorities risk flying blind just as new inflationary pressures begin to build.