Beyond Iran: Where Is Syria Importing Oil From?

- Issue 15

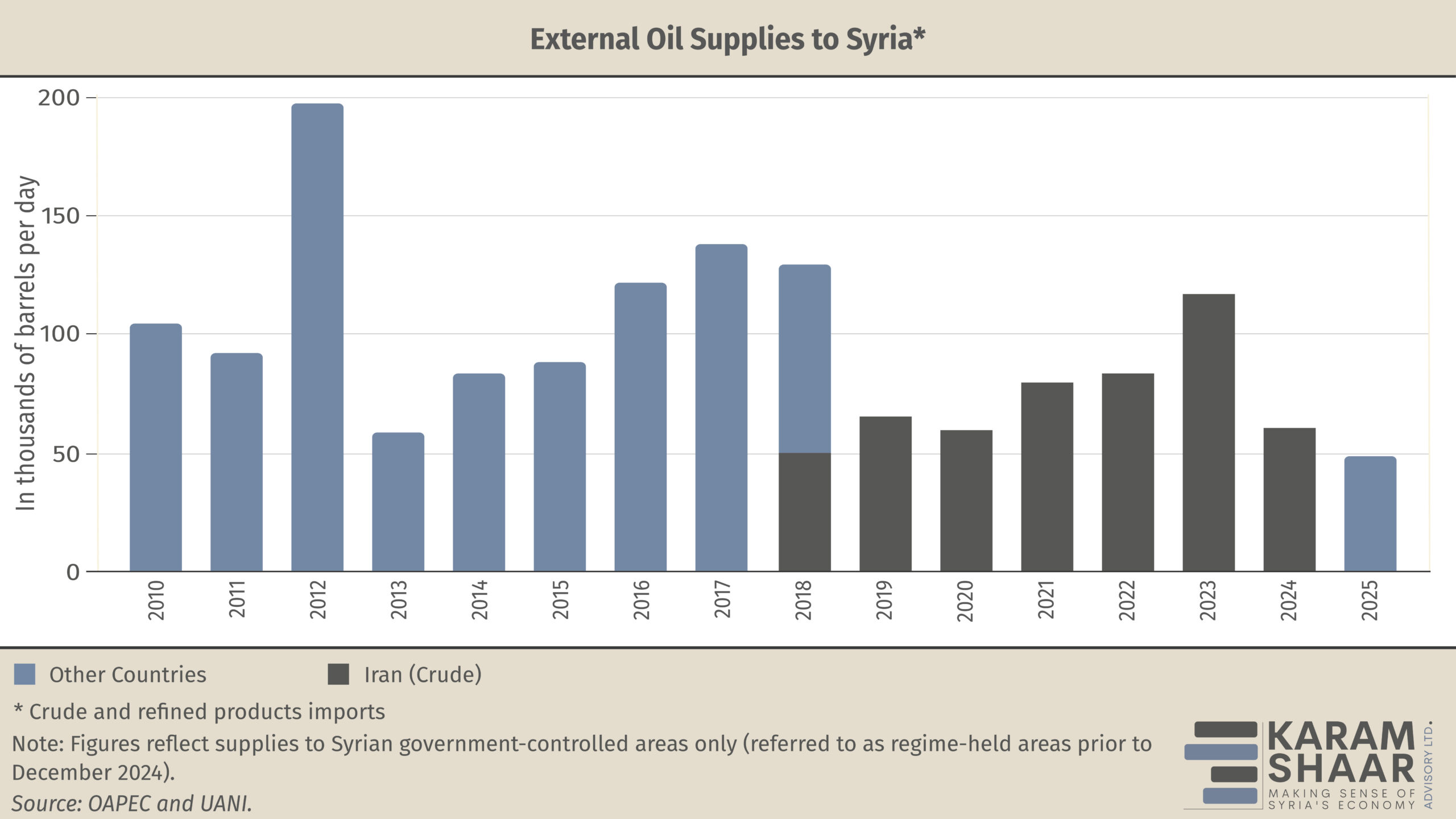

On the eve of the Assad regime’s collapse in December 2024, an Iranian oil tanker bound for Syria made a U-turn in the Red Sea. Once an oil exporter producing around 150,000 barrels per day (bpd) in 2010, Syria had, during the conflict, become dependent on Iranian oil imports. Between 2011 and 2024, Iran reportedly provided approximately USD 14 billion worth of oil and petroleum derivatives, averaging about 78,500 bpd during the final five years of Assad’s rule. These supplies were financed through credit lines. Assad’s fall caused the immediate collapse of this oil-supply arrangement, resulting in an acute shortage and forcing Syria to seek alternative sources of oil supply.

The Caretaker Government—formed after the regime’s fall—responded to the crisis and, on 20 January 2025, announced several tenders for importing 4.2 million barrels of crude oil and approximately 2.8 million barrels of refined products. All tenders attracted no or only negligible responses, as major suppliers remained hesitant to enter payment arrangements with the new Syrian authorities, particularly given the continued presence of sanctions at the time.

Reports indicated that, at the beginning of January, the Iraqi government resumed oil supplies under a mechanism in place since the previous regime era, estimated at around 33,000 bpd, following signals from the US and Türkiye emphasizing its importance in supporting the new Syrian administration. The new quantities were not disclosed, and no further information was provided on whether these imports remain active. This ambiguity was reinforced after the Iraqi Ministry of Oil denied the existence of such supplies altogether, although it remains unclear whether this denial was intended to shield Iraq from potential sanctions.

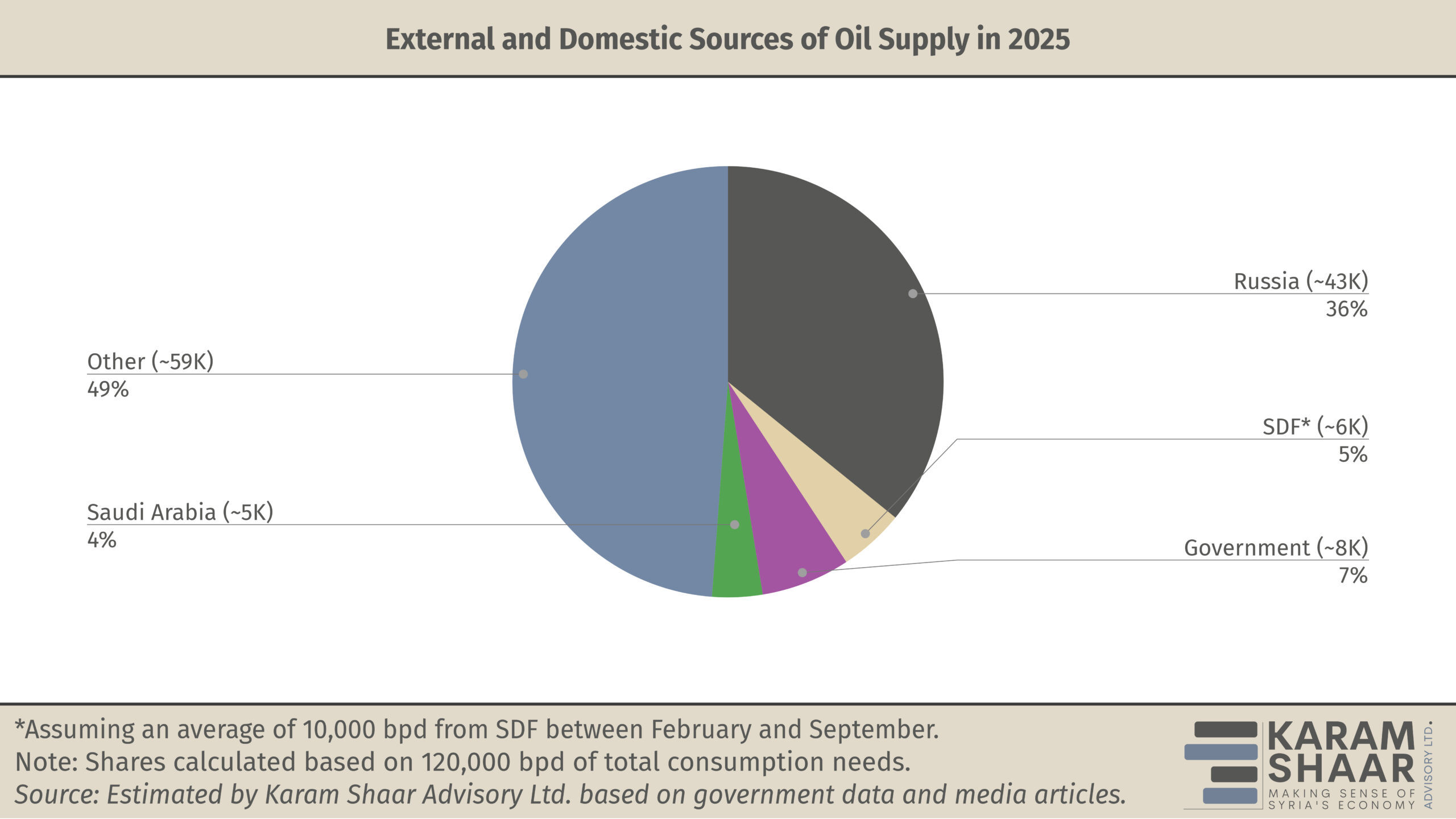

Seeking to secure short-term domestic oil supplies, the government concluded an urgent agreement with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in late February 2025. Sources differed on the quantities to be supplied from the fields in Al-Hasakah and Deir Ezzor to government-held areas, but estimates ranged between 5,000 and 15,000 bpd. The three-month arrangement was renewed in June 2025.

Meanwhile, as sanctions began to ease, the authorities announced additional tenders in March 2025 to procure 7 million barrels of light crude. The same tender was reannounced in June, apparently because the earlier round received no positive responses. The Ministry of Energy likewise announced no results for that tender, indicating that no offers were received. The most recent tender, announced in November, is a further repetition of the previous ones; however, Youssef Qabalaoui, CEO of the Syrian Petroleum Company, revealed that the tender was awarded to a company without disclosing its name.

These volumes were clearly insufficient to close the domestic demand gap. Syria subsequently turned to Russia to source oil, with the first shipment reported to have arrived in early March. By the end of October 2025, Russia had sent 17 shipments totaling more than 15.7 million barrels. We have found no evidence of Russian supplies through November and December.

Russia became Syria’s dominant external oil supplier following the Iranian cutoff, delivering approximately 58,000 bpd of crude oil between March and October 2025. Saudi Arabia, in turn, granted 1.65 million barrels of light crude in November as part of efforts to support the Syrian government’s economic recovery. With the arrival of Saudi oil, Syria gained an additional 27,500 bpd, sufficient through the end of the year, according to Qabalaoui.

Separately, the government controls several oil fields in the west Euphrates and the Badia, producing approximately 8,000 bpd, according to the Minister of Energy, who revealed that total consumption needs are estimated at 120,000 bpd.

The arrangement with the SDF, renewed in June 2025, reached maturity by October. It was expected that this period would see tangible steps toward a transition involving the handover of the Deir Ezzor fields to the Syrian government; however, this did not materialize. No announcements were issued regarding the renewal of the expired arrangement. More recently, Ahmad Yousef, co-chair of the Finance Authority of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, revealed that Damascus has halted oil supplies from Kurdish-controlled fields that had begun in February. The resulting shortfall in SDF-supplied oil was more than offset by the Saudi grant throughout the remainder of 2025, strengthening the Syrian government’s negotiating position with the SDF.

Furthermore, over the course of 2025, a report noted an expansion in the smuggling of refined petroleum products from Lebanon into Syria. Petroleum imports into Lebanon rose by 39% in the first half of 2025—an increase of nearly 38,000 bpd compared to the same period in 2024—far exceeding growth in Lebanese domestic demand. The report aligns our findings (see chart above), indicating that approximately 59,000 bpd remain of unknown origin, highlighting the significant role of smuggling and illegal trade in bridging the gap in demand for oil and its derivatives. Other potential sources for supplying petroleum products might be the companies that used to secure the demand in northwest Syria before 2025 and remained active, and even expanded throughout the Syrian territory after the collapse of the regime.

To muddy the picture further, the Syrian government resumed oil exports, a step misinterpreted by many news outlets as a return to pre-conflict net exporter status. However, the easing of sanctions following the regime’s collapse enabled the government to return to international markets as an exporter, not because of excess supply, but because of the lack of refining capacity.

In June 2025, a shipment of about 256,000 barrels (29,871 tonnes) of naphtha was exported through the Baniyas terminal. While the destination remains officially unknown, our research indicates that the cargo was bound for Europoort Rotterdam in the Netherlands, based on vessel-tracking data. This was followed by a more significant milestone in September 2025, when Syria shipped 600,000 barrels of heavy crude oil via the Tartous terminal. The buyer was reported to be B SERVE ENERGY DMCC, a virtually unknown entity with no prior trading history. Although initial media reports erroneously linked the deal to BB Energy—a mistake later corrected by Reuters—our tracking of the physical movement of the cargo suggests a different connection. According to our investigation, the oil was loaded onto the Nissos Christiana, a tanker managed by Kyklades Maritime Corporation with a documented history of chartering for Vitol Group. Notably, the vessel’s final destination was Sarroch, Italy, home to the Sarlux refinery controlled by Vitol following a partial acquisition in 2024. Such purchases, under the suspension of the Caesar Act and the lifting of EU sanctions, did not contravene any sanctions against Syria.

With the Homs refinery, which specializes in heavy crude processing, largely deteriorated, some of this oil is unusable domestically. Exporting it generates hard currency to import refined fuels or light crude for processing at the Baniyas refinery. Officially, the origin of the exported oil remains unclear, although most of Syria’s heavy oil is known to be located in the northeast, largely outside direct government control at present.

In 2025, Syria sourced oil through multiple channels, including Russian crude, Saudi assistance, supplies from the SDF, limited domestic production, and regional smuggling networks. Despite this diversification, the country was unable to secure reliable energy provision, primarily because it could not freely procure oil on international markets through tenders, a problem that is likely to ease with the recent lifting of the Caesar Act but will not entirely disappear given the country’s continued disconnectedness from the global banking system. Moreover, existing supply arrangements have proven unstable, as illustrated by the discontinuation of the deal with the SDF, the one-off Saudi grant, and the likelihood of pressure from the US administration regarding the reliance on Russian supplies, all of which may force Damascus to seek alternative sources.

Achieving a more sustainable supply will require Damascus to rapidly conclude a comprehensive agreement with the SDF in order to restore unified control or arrive at a production sharing agreement over national resources. According to the Syrian Minister of Energy, the SDF is currently producing between 80,000 and 110,000 bpd. With Saudi assistance largely exhausted and continued negotiations with the SDF, Syria faces a critical juncture that could result in renewed energy shortages in early 2026, particularly in light of a forecasted future spike in consumption. The country’s outlook will therefore depend heavily on the outcome of talks between Damascus and the SDF, as well as parallel negotiations with Iraq to activate the Kirkuk–Baniyas pipeline, which will be examined in later issues of Syria in Figures.