The Syrian People’s Assembly 2025: Electoral Results and Representation Gaps

- Issue 15

Nearly a year after Assad’s toppling, the October 2025 parliamentary elections marked the first institutional test of the transitional period. While the new People’s Assembly operates within an incomplete constitutional framework—most notably lacking a Supreme Constitutional Court and a High Judicial Council, which constrains its independence and oversight capacity—this article focuses on a different question: how representative the Assembly’s elected members are of Syrian society, ahead of the President’s outstanding appointments.

Using a bespoke database of all elected members compiled through open-source investigations, we developed an interactive tool on the Syrian People’s Assembly that allows users to track members across key demographic and professional variables and assess overall representation.

The 2025 elections were conducted under an indirect system established by two public decrees, which created the High Elections Commission (HEC) and set the Assembly at 210 members: 140 indirectly elected and 70 appointed by the President. Sub-electoral bodies were formed across 50 districts based on predetermined criteria—70% academically qualified professionals and 30% notables and community leaders—and held full authority to nominate and elect candidates.

Security and political conditions prevented elections in As-Suwayda, Raqqa, and Hasakah governorates, limiting the first round to 119 elected members. Supplementary voting in Ras al-Ain (Hasakah) and Tal Abyad (Raqqa) raised the total to 122. Elections in the remaining districts have not been completed and no timeline has been announced. The Assembly will be completed through 70 presidential appointments, intended to address representation gaps resulting from the partial and indirect nature of the process.

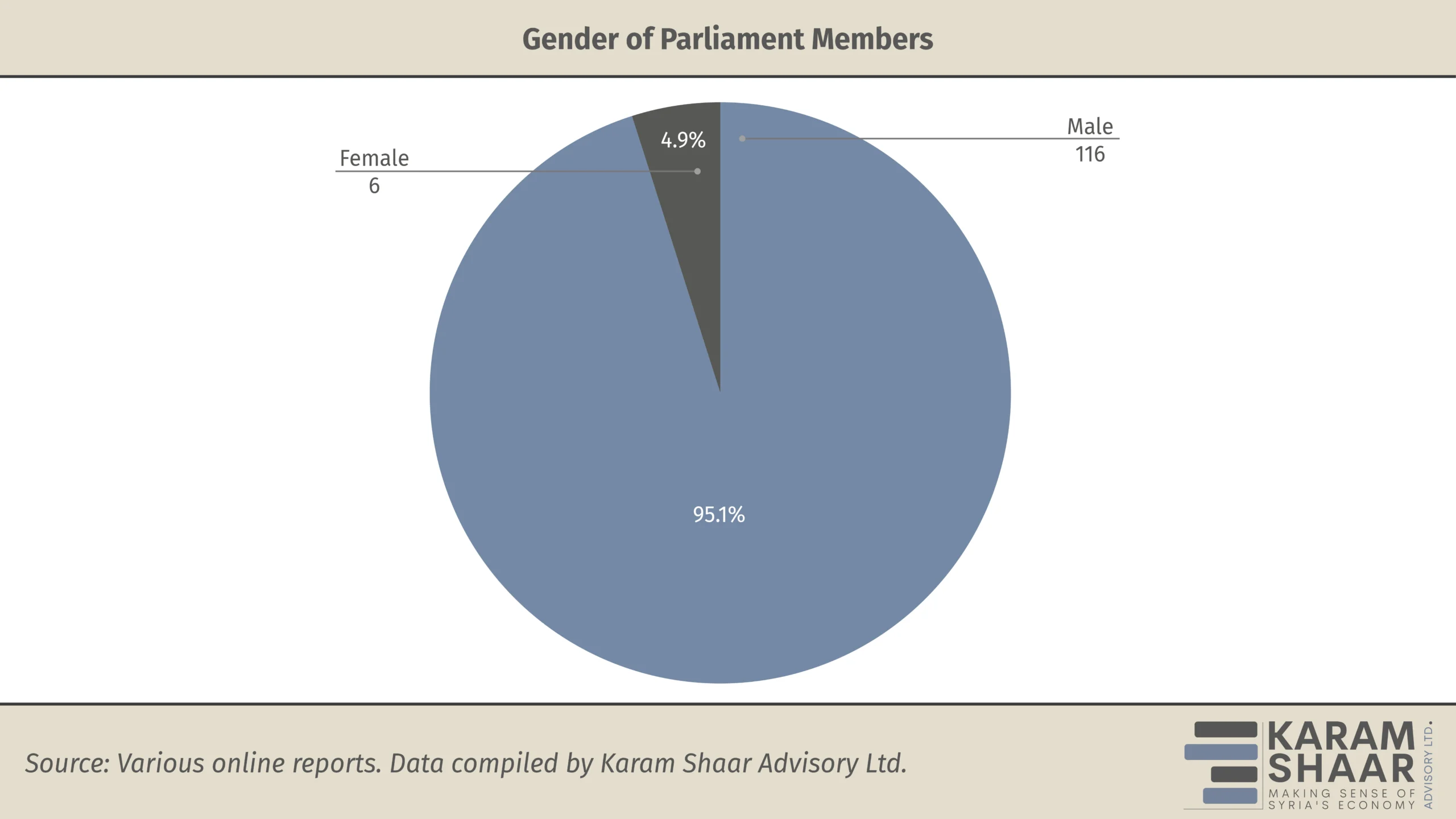

Weak representation of women

Female representation in the Assembly is extremely low. Women account for just 4.9% of elected members (6 out of 122), down from 11.2% (28 out of 250) in the 2020 parliament—the most recent legislature for which a comparable dataset exists. This outcome is partly explained by the candidate pool: women constituted only 14.1% of candidates (221 out of 1,571). Official statements suggest that presidential appointments may help address this imbalance.

This underrepresentation reflects entrenched social barriers as well as procedural flaws. The Higher Electoral Committee included only two women among its eleven members, while the electoral colleges responsible for candidate selection were overwhelmingly male and embedded in local networks that limit women’s access to meaningful competition—a pattern common to patriarchal societies worldwide, including across the Middle East.

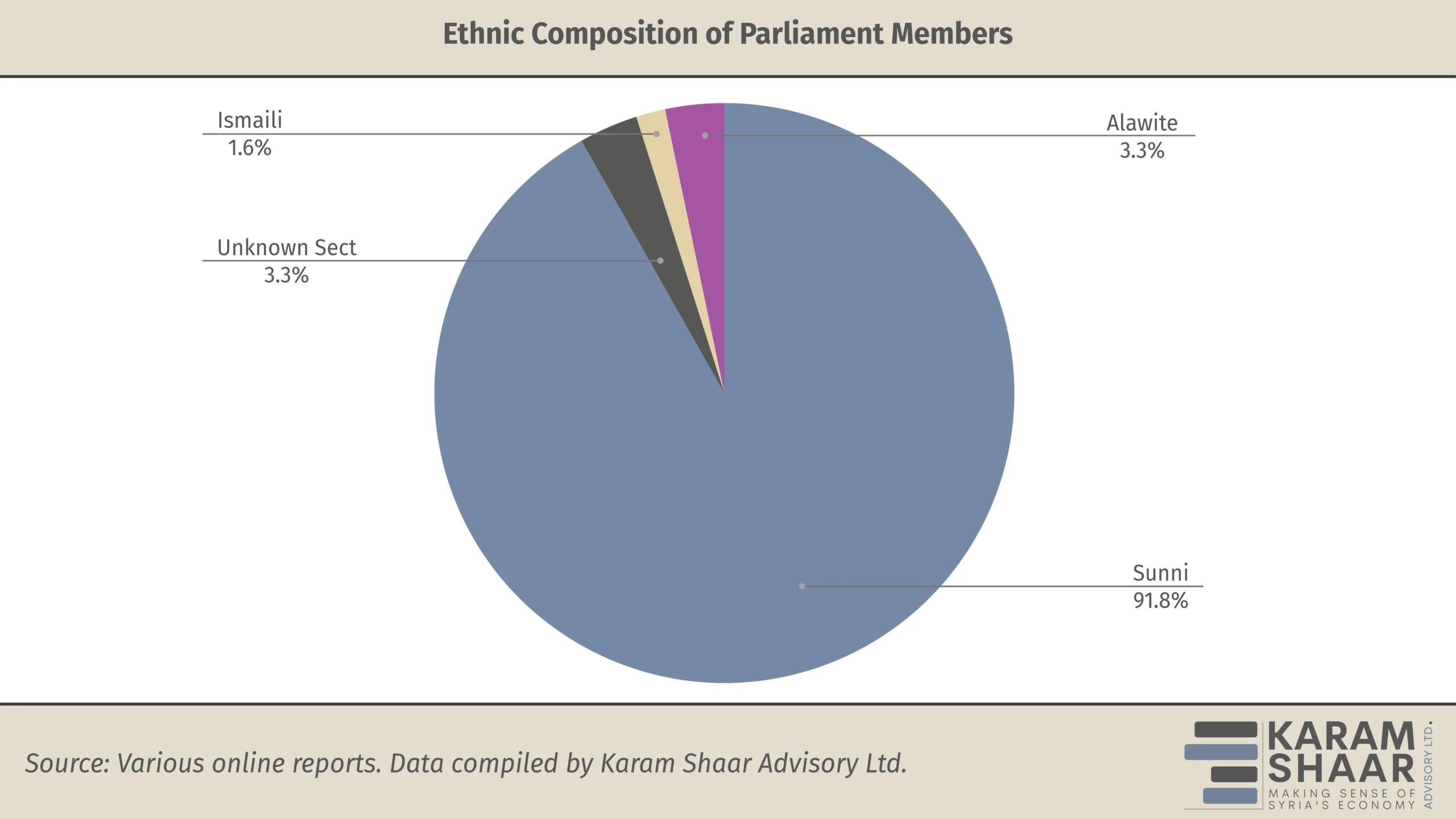

Religious and ethnic imbalances

Of the 122 elected members, 120 are Muslim (98.4%) and one is Christian (0.8%), compared to Christians’ estimated 2.3% share of the population in 2024, which would correspond to roughly two to three seats in an Assembly of this size. While two Christian winners were officially announced, only one could be independently verified; if the second is confirmed, Christian representation would be broadly consistent with population estimates.

At the level of Islamic sects, Sunni Muslims account for 92.4% of members whose backgrounds could be verified. Alawites hold only four seats (3.3%), all elected from Latakia and Tartous, with none from Homs despite the presence of a sizable Alawite population there. This is well below the community’s potential 12% share of the population. The Druze community has no representation, a direct result of the exclusion of As-Suwayda—the only majority-Druze governorate—from the electoral process. This absence persists despite the presence of Druze communities in parts of Rural Damascus, including Jaramana, which produced no elected representatives identifying as Druze.

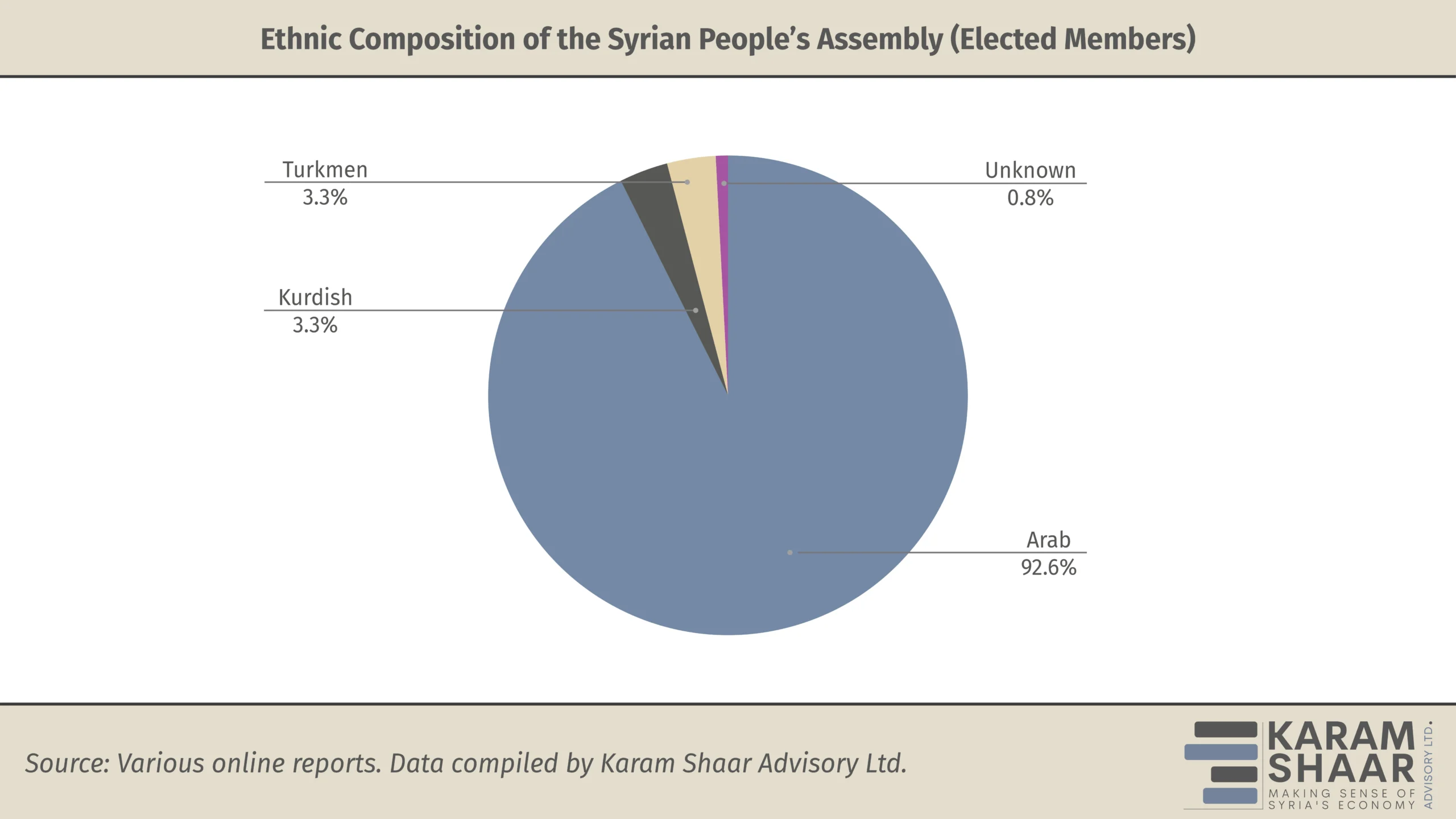

Ethnically, the Assembly is overwhelmingly Arab. Kurdish representation is limited to four members, all elected from Afrin, and does not reflect the community’s broader population base, particularly in Hasakah, where elections were not held. Smaller minorities, including Syriacs, Assyrians, and Circassians, are entirely absent.

Overall, the underrepresentation of Kurdish and Druze communities is closely linked to the absence of elections in areas where they are primarily concentrated. The most structurally significant imbalance, however, concerns Alawites and can be explained by multiple factors, including the community’s boycott of the electoral process following the coastal massacres, resistance to Alawite participation—manifested in the assassination of a candidate from Tartous—and, most importantly, the weak representation of Alawites within the electoral colleges themselves.

Individual and professional representation

In the absence of legalized political parties and program-based campaigning, the elections did not produce identifiable ideological blocs or organized alignments within the Assembly. Members’ backgrounds are not mutually exclusive. Approximately 28.7% of the elected members previously served in official opposition institutions, 19% came from pre-2011 state institutions, and 16.4% had prior ties to armed opposition groups before transitioning into civilian roles. By contrast, 62.3% of members have no identifiable political or military background and are best described as independents, technocrats, or local notables whose influence derives primarily from social standing rather than party orientation.

Policy Recommendations

Ensuring meaningful representation—particularly for severely underrepresented groups such as women and Alawites—should not be treated as a tokenistic means of gaining domestic or international legitimacy. It is a prerequisite for a stable and inclusive post-conflict order and a key determinant of policy quality.

To strengthen the legitimacy of the new parliament and anchor it within a stable political system, the transitional presidency should prioritize completing the electoral process in governorates excluded from voting. Doing so will require political compromises with de facto authorities in those areas. Their continued exclusion has left major segments of Syrian society, including Druze and Kurdish communities, without meaningful representation at the center of decision-making.

Presidential appointments constitute a second, critical mechanism for addressing the structural gaps identified in this analysis. These appointments should follow transparent criteria explicitly aimed at improving the representation of marginalized groups and underrepresented political currents.