Syria’s Gas Sector: Recovery Under Pressure

- Issue 10

Syria’s gas sector—once central to electricity supply—has suffered over a decade of conflict-driven decline. As of mid-2025, output remains well below pre-war levels. Infrastructure is destroyed, and foreign investment depends on fragile political and legal arrangements. Still, modest recovery efforts are underway, with regional gas deals and targeted repairs providing relief.

Reserves

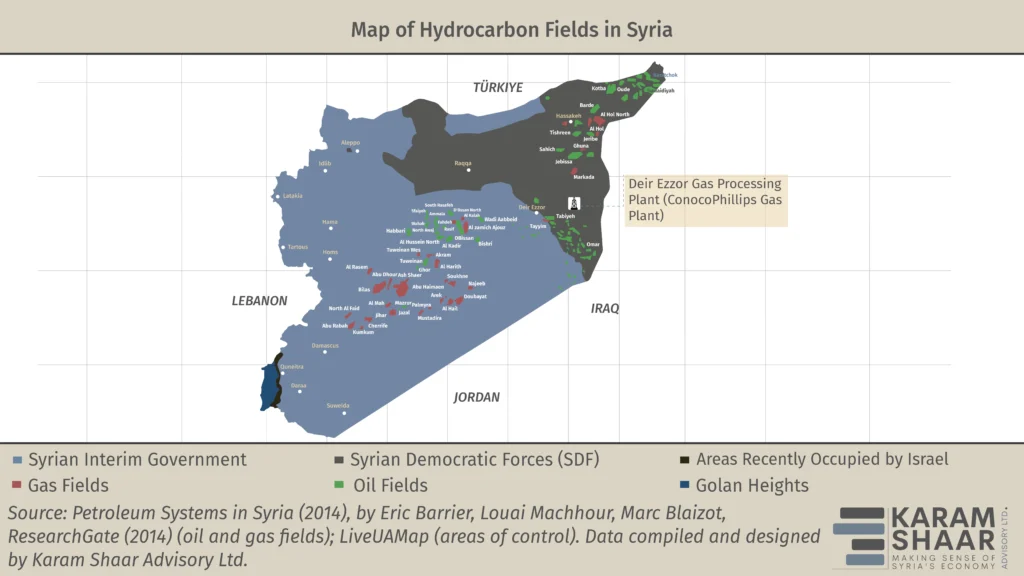

The country reportedly holds an estimated 240 billion cubic meters (cm) of natural gas reserves, mostly in areas controlled by the Damascus government (see the map below). This is in contrast to oil reserves, which are primarily located in control areas of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

The main onshore fields, including al-Shaer, Hayyan, Tuwienan, Maher, Jazal, and Furqlus, are located in the desert east of Homs. Smaller associated fields, such as Omar and Jafra, are in Deir Ezzor. The Conoco gas plant—the largest in the country—is located in SDF-held territory east of the Euphrates. With a processing capacity of up to 13 million cm per day (cmd), it is a chokepoint for the entire sector.

Most of the major fields were awarded to international companies prior to 2011 as joint operation companies with the former Assad government. For example, Suncor Energy (which merged with Petro-Canada in 2009, retaining it as a subsidiary and retail brand) operated the Ebla Gas Plant, extracting gas from the al-Shaer and Sherife fields near Palmyra. INA Naftaplin ran the Jihar Gas Plant, extracting gas from the Jihar and al-Mahr gas fields further east. Following the outbreak of conflict, both companies declared force majeure and suspended operations.

As of July 2025, the status of these gas contracts remains unclear, as explained in the February 2025 issue of Syria in Figures. The Interim Government has since issued various calls for international companies to return, and even met with representatives of Gulfsands Petroleum in Damascus to discuss possible re-engagement.

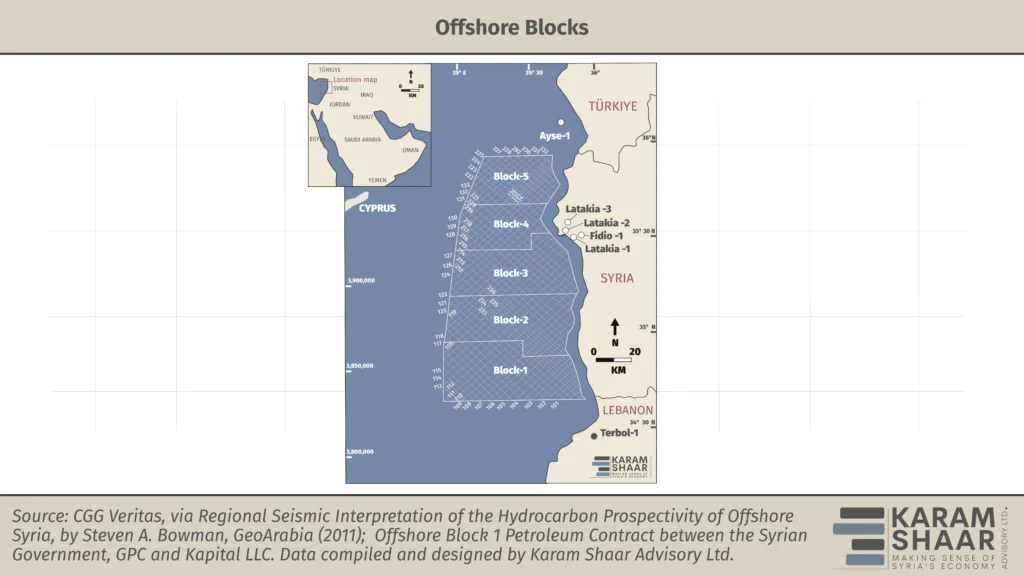

In recent years, attention has also turned to offshore potential. While no verified figures are available, former oil and mineral resources minister Ali Ghanem claimed reserves could reach 250 billion cm. Broader estimates for the Levant Basin—which includes Lebanon, Palestine, Cyprus, and Israel—stand at around 3.47 trillion cm, though the size of Syria’s share is unknown. Seismic surveys have hinted at “encouraging results” off the coast, but thus far drilling in Lebanon’s offshore sites has not led to the discovery of oil.

Two offshore blocks were granted to Russian firms during the conflict. Block 2 went to Soyuzneftegaz in 2013 (though they gave up on it in 2015 because of the continuing conflict), and Block 1 to Kapital LLC in 2022. At the time of the Assad regime’s collapse, it was unclear whether any exploration or commercial activity had commenced. There is still no evidence that any work took place. The current status of both agreements remains uncertain.

Production and usage

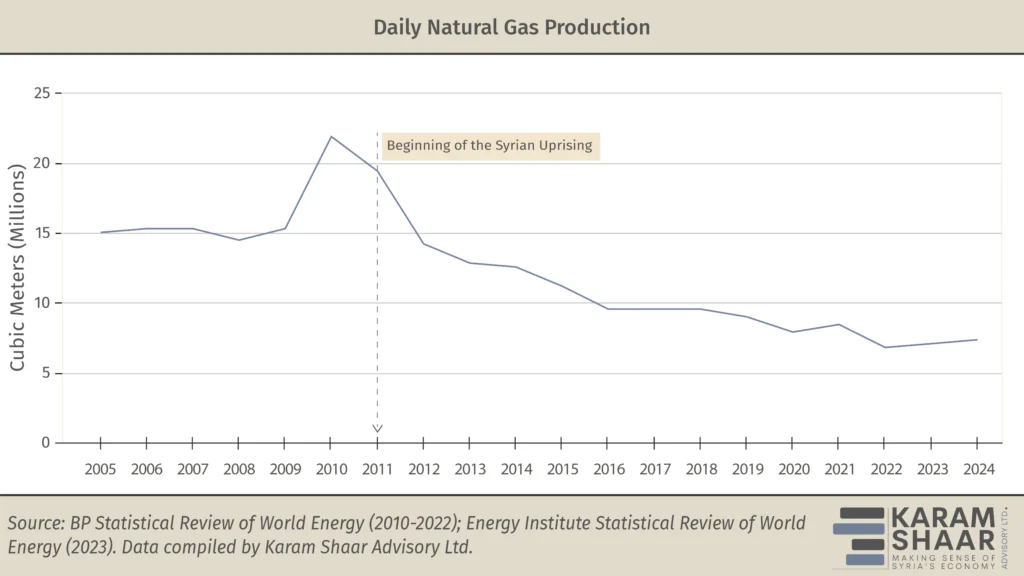

Natural gas production fell from over 21.9 million cmd in 2010 to approximately 7.4 million cmd by 2024, according to the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy. As of January 2025, the caretaker Minister of Oil and Mineral Resources reported production in government-held areas at 8 million cmd, with an additional 1.1 million cmd extracted by the SDF. However, this output has since been halted—and it remains unclear whether production has resumed.

This decline has significantly affected both the country and its population, as natural gas is primarily used for two essential purposes: electricity generation, and domestic and industrial consumption.

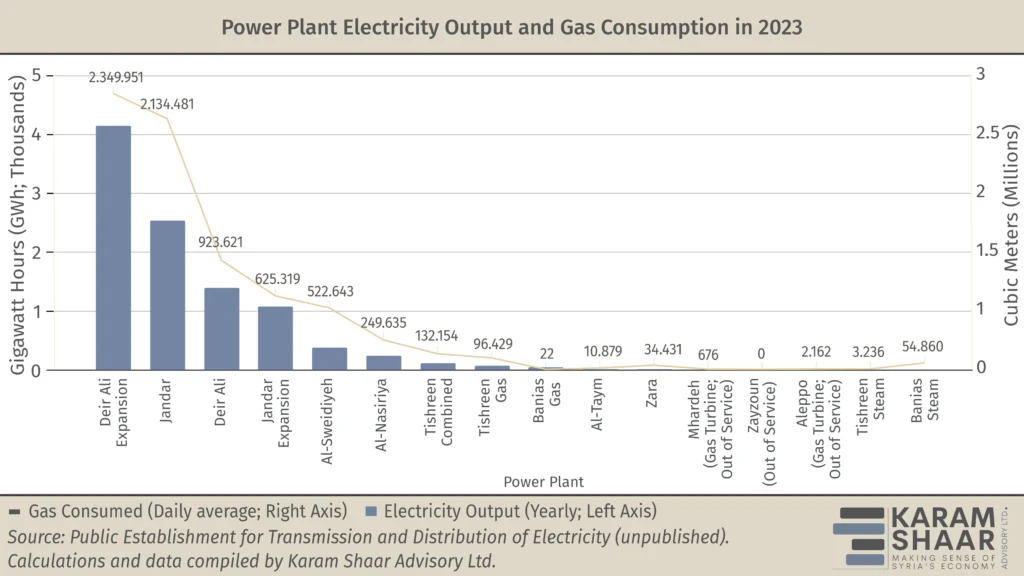

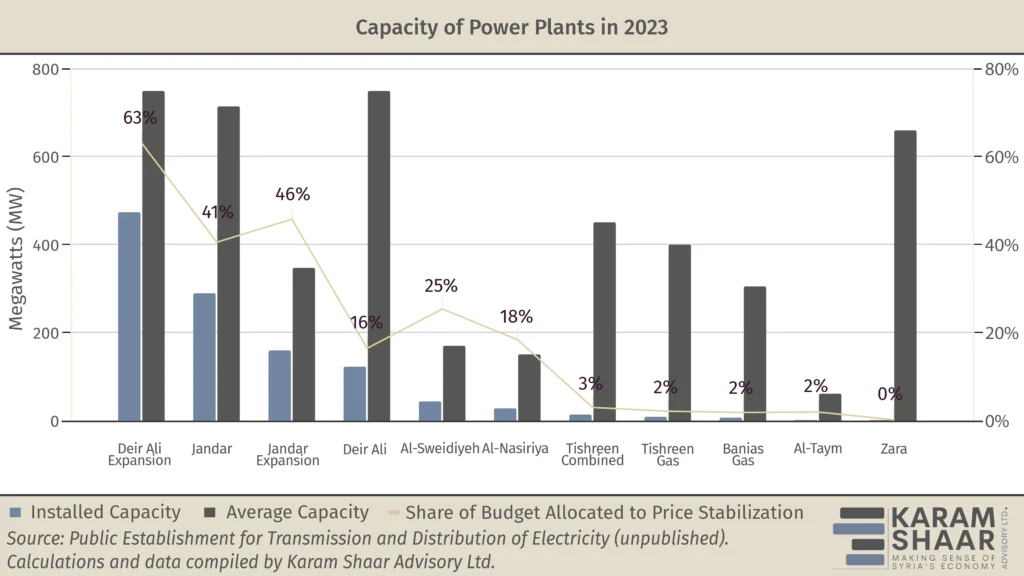

In terms of electricity, Syrian officials estimate that 23 million cmd are needed to meet national demand; this figure is roughly three times current production. Due to gas shortages, gas-fired power generation fell to just 10,022 GWh in 2023, compared to a potential 41,656 GWh based on existing capacity, according to official and unpublished data accessed by Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd. For more on installed capacity, see our earlier Syria in Figures article.

Other sources—primarily fuel oil and hydro—contributed an additional 8,262 GWh in 2023. Even so, electricity supply remains far below needs. The national grid faced a 25,409 GWh shortfall relative to the estimated demand of 43,693 GWh, according to the unpublished Public Establishment for Transmission and Distribution of Electricity’s (PETDE) 2023 annual report accessed by Karam Shaar Advisory.

Domestically, gas is used for cooking and heating. As of early July 2025, these remained heavily subsidized via the Smart Card system and sold at USD 2 per canister (see our article on subsidies below). In practice, however, conflict has reduced availability, resulting in shortages of subsidized gas. Cooking gas has been more accessible on the black market, but often at ten times the official price.

In 2019, local production covered only 35 percent of daily canister demand—roughly 400 tonnes out of the 1,200 tonnes required. Since then, no reliable data on gas usage or production has been published. Still, persistent shortages and rising prices indicate that the supply gap remains severe.

Securing gas supplies

Following the collapse of the Assad regime, several international actors have stepped in to help address the country’s gas deficit, including supplies of cooking gas. Jordan provided 5,000 tonnes of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in January 2025, primarily for household and industrial use. Based on 2019 consumption figures mentioned above—now likely outdated—this shipment would have covered just over four days of national demand.

Qatar and Türkiye have also moved to support the energy sector by supplying natural gas for power generation (see Syria in Figures, Issue 9: June 2025). Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has also taken a concrete step: in mid-June 2025, its state oil company SOCAR signed a memorandum of understanding with the Syrian government to supply natural gas.

These deliveries may help alleviate the shortfall and partially restore electricity supply. Of the country’s 4,755 MW in gas-fired generation capacity, only 1,144 MW was operational as of early 2025 (see chart below).

However, such stopgap measures are no substitute for a long-term solution.

One possible path forward lies in renewed cooperation between Damascus and the SDF. On 10 March 2025, the then-Caretaker Government and the SDF signed a landmark agreement to begin negotiations on joint management of oil and gas resources. If implemented, this could enable unified oversight, attract investment, and create the conditions for eventually restoring full utilization of the Conoco plant’s potential 13 million cmd processing capacity, fed by the Tabiyeh, Omar and Tayyim fields. Combined with the 8 million cmd already produced in government-held areas, this would reduce daily shortfall to just 3 million cmd.