The Syrian Public Sector: Restructuring the State After Assad

- Issue 11

The Interim Government has begun shifting toward a market-oriented model, reducing the state’s role as the primary employer. Authorities have launched a three-pronged process: stabilizing payroll management through a unified employee database and salary adjustments; reviewing staffing through dismissals and reinstatements; and drafting a new civil service law to lay the foundation for long-term reform.

Workforce Numbers and Payroll Pressures in Transition

The first measure to address dysfunction in the public sector has focused on restoring payroll integrity amid disputes over the true size of the state workforce. In 2022, the number of public employees stood at about 1.5 million, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. This represented a 6.0% increase compared to 2011—an unlikely rise given the scale of displacement, economic collapse, territorial fragmentation, and administrative breakdown in the areas outside the government’s control. In fact, a 2024 study by the Institut National d’Administration (INA) in Damascus found that five ministries lost over 50% of their workforce between 2010 and 2022.

In January 2025, the caretaker Finance Minister acknowledged that only 900,000 of the roughly 1.3 million people then on the payroll were actually showing up to work, exposing the extent of ghost employment.

Several factors explain this: many had informally resigned, as formal resignation is often blocked or delayed, making quitting technically illegal. However, the larger factor likely stems from corruption: individuals receiving salaries without showing up to work, and outright employment of people under fake names. These salaries may have been siphoned off by complicit employees, as seen in other contexts such as Kenya, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

To address these problems, the Interim Government launched a Unified National Employee Database in April 2025. According to the Ministry of Administrative Development (MOAD), the database is intended to improve oversight, reduce corruption, and support evidence-based reform. At the same time, MOAD launched a digitization project aimed at preserving and archiving employee records. It should be noted, however, that projects of this scale typically take years to complete, making the reported speed and scope of these initiatives difficult to verify.

In January 2025, the government announced a 400.0% salary hike for public employees. However, payroll audits uncovered inflated rosters, delaying the measure. By June 2025, following adoption of the unified database, the government proceeded with a 200.0% raise instead. While the Minister of Finance attributed the smaller increase to irregularities in payroll records, our analysis suggests the more likely reason was a lack of fiscal space to finance such a large raise without fueling inflationary pressures.

Such increases were nonetheless critical. In 2022, over a million public employees earned just USD 20–33 per month (see table below), while a standard food basket for a family of five cost USD 67. The 200.0% salary increase therefore provided significant relief for hundreds of thousands of families.

The recent increase is estimated to add USD 762 million to the annual wage bill, according to our calculations, or nearly 30% of the state’s projected 2024 revenue. Qatar pledged partial and temporary support, which has yet to arrive. Without more external aid, concerns remain that the gap is being covered through money printing and subsidy cuts, fueling inflation.

Public Sector Employees by Salary Range in 2011 (Exchange Rate: 1 USD = 47 SYP) |

||

| Salary Bracket (USD) | Salary Bracket (SYP) | Number of Employees (% of Total) |

| 192+ | 9,001+ | 1,066,521 (78.4%) |

| 170 – 192 | 8,001 – 9,000 | 99,980 (7.4%) |

| 149 – 170 | 7,001 – 8,000 | 86,399 (6.4%) |

| 127 – 149 | 6,001 – 7,000 | 38,771 (2.9%) |

| 106 – 127 | 5,001 – 6,000 | 14,322 (1.1%) |

| < 106 | < 5,000 | 54,028 (4.0%) |

| Total | 1,360,021 | |

Public Sector Employees by Salary Range in 2022 (Exchange Rate: 1 USD = 4,491 SYP) |

||

| Salary Groups (USD) | Salary Groups (SYP) | Number of Employees (% of Total) |

| 100+ | 450,000+ | 1,208 (0.1%) |

| 73 – 100 | 330,001 – 450,000 | 1,242 (0.1%) |

| 60 – 73 | 270,001 – 330,000 | 16,673 (1.2%) |

| 47 – 60 | 210,001 – 270,000 | 32,360 (2.2%) |

| 33 – 47 | 150,001 – 210,000 | 274,595 (19.0%) |

| 20 – 33 | 90,001 – 150,000 | 1,069,673 (74.0%) |

| < 20 | < 90,000 | 52,144 (3.6%) |

| Total | 1,447,895 | |

| Source: Central Bureau of Statistics. Data compiled by Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd. | ||

Dismissals and Reinstatements in the Post-Assad Public Sector

The second major intervention focused on purging and correcting the composition of the workforce. In the wake of the regime’s fall, the caretaker authorities pledged to restructure public employment to downsize the bureaucracy, leading to mass dismissals. Ministries and state-owned enterprises were reportedly instructed to terminate the contracts of employees accused of corruption, absenteeism, or complicity in crimes against civilians.

In December 2024, the Spokesperson for Political Affairs of the caretaker government announced that employees who had “committed crimes and harmed the population will be dismissed and held accountable,” with the Caretaker Minister of Administrative Development aiming to reduce the public workforce by “more than half.” These dismissals, however, intended as a form of accountability and fiscal responsibility, lacked due process. They provoked widespread protests under slogans such as “No to Arbitrary Dismissals,” with demonstrations breaking out in several cities including Damascus, Sweida, and Aleppo.

The restructuring process has unfolded unevenly. Some ministries placed employees on paid leave, while others dismissed them outright. In some cases, ministries reversed dismissals; in others, employees were required to retake qualification exams before returning to work.

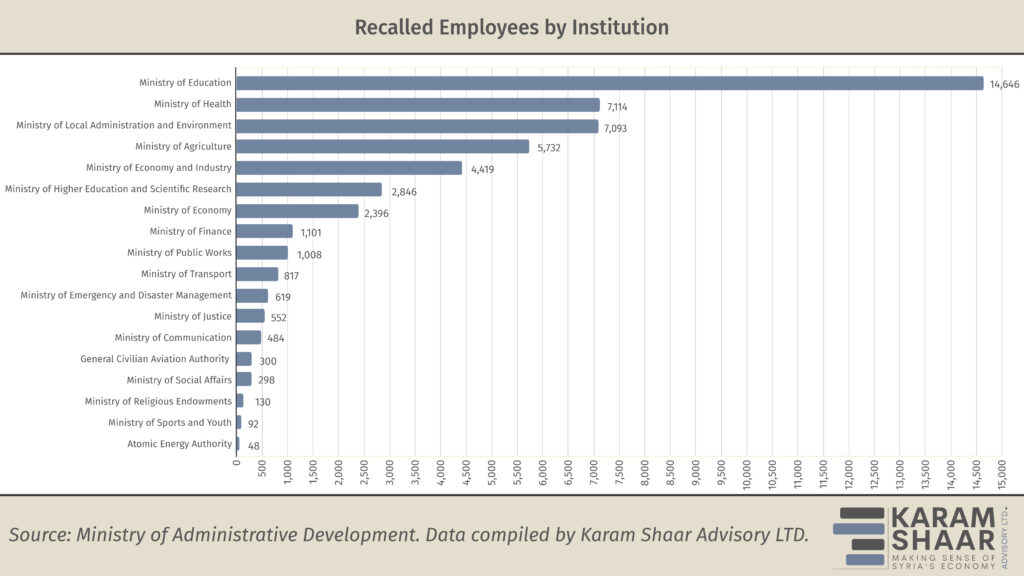

Alongside this poorly coordinated and partially reversed policy, the government has also opened a parallel track of reinstatements, particularly for civil servants expelled by the Assad regime for supporting the 2011 uprising. The first wave of recalls came on 14 April 2025, with 14,646 employees in the Ministry of Education invited to return to their original departments. Since then, MOAD has stepped up efforts to restore these workers to their posts. As of 18 August 2025, 49,800 former employees have been invited to return to their original departments (see below).

Another major development has been the dismissal of security and armed forces. Although precise figures remain unclear, the Syrian Arab Army was estimated at around 220,000 troops as of 2011. While their removal eases the state’s payroll burden, it has the potential to generate serious social and security challenges, similar to what happened in Iraq when thousands of former officers and conscripts suddenly lost both income and status. Those challenges in turn risk fueling social unrest and the emergence of armed networks outside state control. In fact, some of these so-called “remnants of the regime” have reportedly regrouped, with some of them playing a role in triggering the violence in the coastal region.

Legal Reform and the Redefinition of Public Employment

The third shift of the public sector transformation lies in the legal overhaul of civil service governance.

In June 2025, MOAD launched the drafting process for a new Civil Service Law to replace Law 50 of 2004, the long-standing legal foundation of public employment. Ministerial Decision 302 formally established a Final Drafting Committee to complete a final version of the law within 45 days—by mid-August 2025.

This reform effort is set to significantly change the public sector’s identity in a post-Assad Syria. According to MOAD, the new law will “promote the principles of merit and equal opportunity” in the civil service. Under the Assad regime, the public sector was marked by rampant corruption across all areas of administration.

This initiative is part of a broader effort to build a more skilled and accountable public sector. In addition to MOAD’s work, Presidential Decrees 43, 44, 45, and 46 introduced new mechanisms for staffing leadership positions and evaluating performance across executive and mid-level posts.

To support administrative reform, MOAD has partnered with institutions like INA and the Higher Institute of Business Administration (HIBA) to develop graduate programs, link students to practical reform projects, and integrate academic expertise into restructuring efforts. A new permanent committee now oversees the placement of INA graduates through interviews with ministries to match skills with institutional needs.

Public sector reform is urgently needed. However, the current direction—while promising—remains fragmented, with state departments sending mixed signals and operating without a clear framework. If managed with transparency and adequate external support, today’s piecemeal measures could evolve into a coherent system for a leaner, more accountable state. The coming months will determine whether this transition cements into lasting reform or slips back into the inefficiencies and patronage that have defined the public sector for decades.