From Solidarity to Strategy: The Rise and Risks of Community Financing in Syria’s Reconstruction

- Issue 13

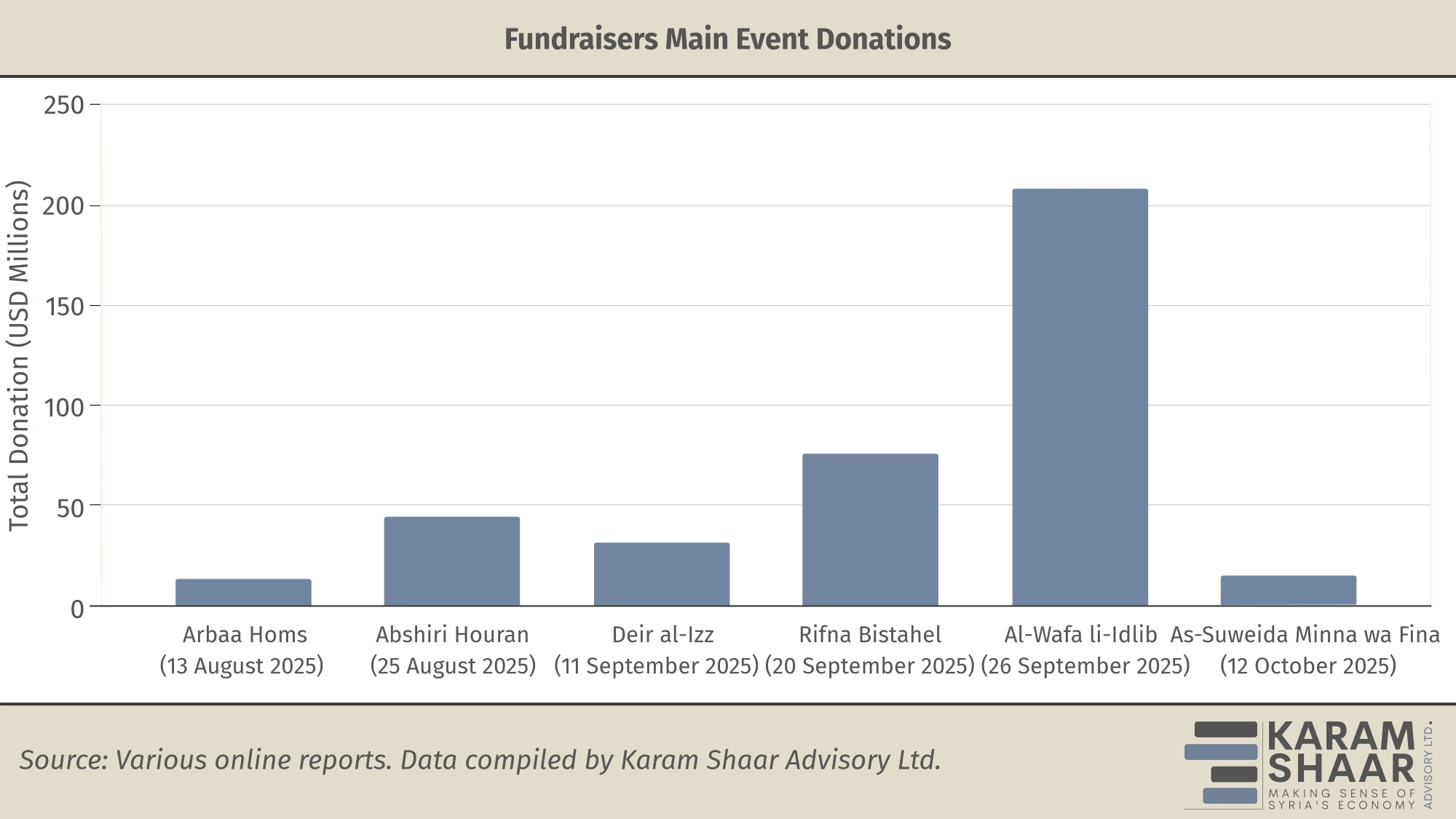

In 2025, Syria witnessed large-scale community donation campaigns bearing locally symbolic names such as Arbaa Homs, Abshiri Houran (in Daraa), Deir al-Izz (in Deir Ezzor), Rifna Bistahel (in Rural Damascus), Al-Wafa li-Idlib, and As-Suwayda Minna wa Fina. These initiatives, alongside smaller ones emerging in local districts, were more than charitable acts: their popularity among Syrians marked milestones in both rebuilding the social fabric and supporting reconstruction by addressing gaps left by years of war. They also demonstrated the ability of Syrians—both at home and abroad—to mobilize collectively and raise substantial resources in a short time, channeling tens of millions of dollars into local recovery.

Yet behind the celebratory tone lies a more complex picture. Much of the pledged money is not new, raising doubts about transparency, accountability, and real impact. Some former regime cronies view these campaigns as a means to regain influence, while questions persist over funding sources, oversight, and strategic direction.

Community Campaigns: From Arbaa Homs to As-Suwayda Minna wa Fina

Between August and September 2025, six major fundraising drives swept across Syrian governorates, each carrying local symbolism and ambitious goals. The table below outlines when they took place, how much they raised, and which sectors they aimed to rebuild.

Our tracking shows that education topped the list of priorities, through the rehabilitation and construction of hundreds of schools in Daraa, Rural Damascus, Deir Ezzor, Idlib, and As-Suwayda. It was followed by the health sector, through the equipping of hospitals, clinics, and medical centers. Funding also extended to infrastructure and public services, such as water and sewage networks, roads, sanitation, and electricity, and finally to housing, through the repair or reconstruction of tens of thousands of homes.

Years of conflict have emptied the state’s coffers, while international aid continues to decline. Hundreds of Syrian localities remain in dire need of reconstruction and basic services. Nearly one-third of the country’s housing stock has been destroyed or severely damaged, and over half of its basic service infrastructure—including water, electricity, health, and education—has collapsed, leaving millions without adequate shelter or essential services. With physical capital destruction estimated at around USD 123 billion, the scale of needs far exceeds the combined capacity of the state, international donors, and local communities—yet Syrians increasingly feel compelled to rely on their own limited means to rebuild.

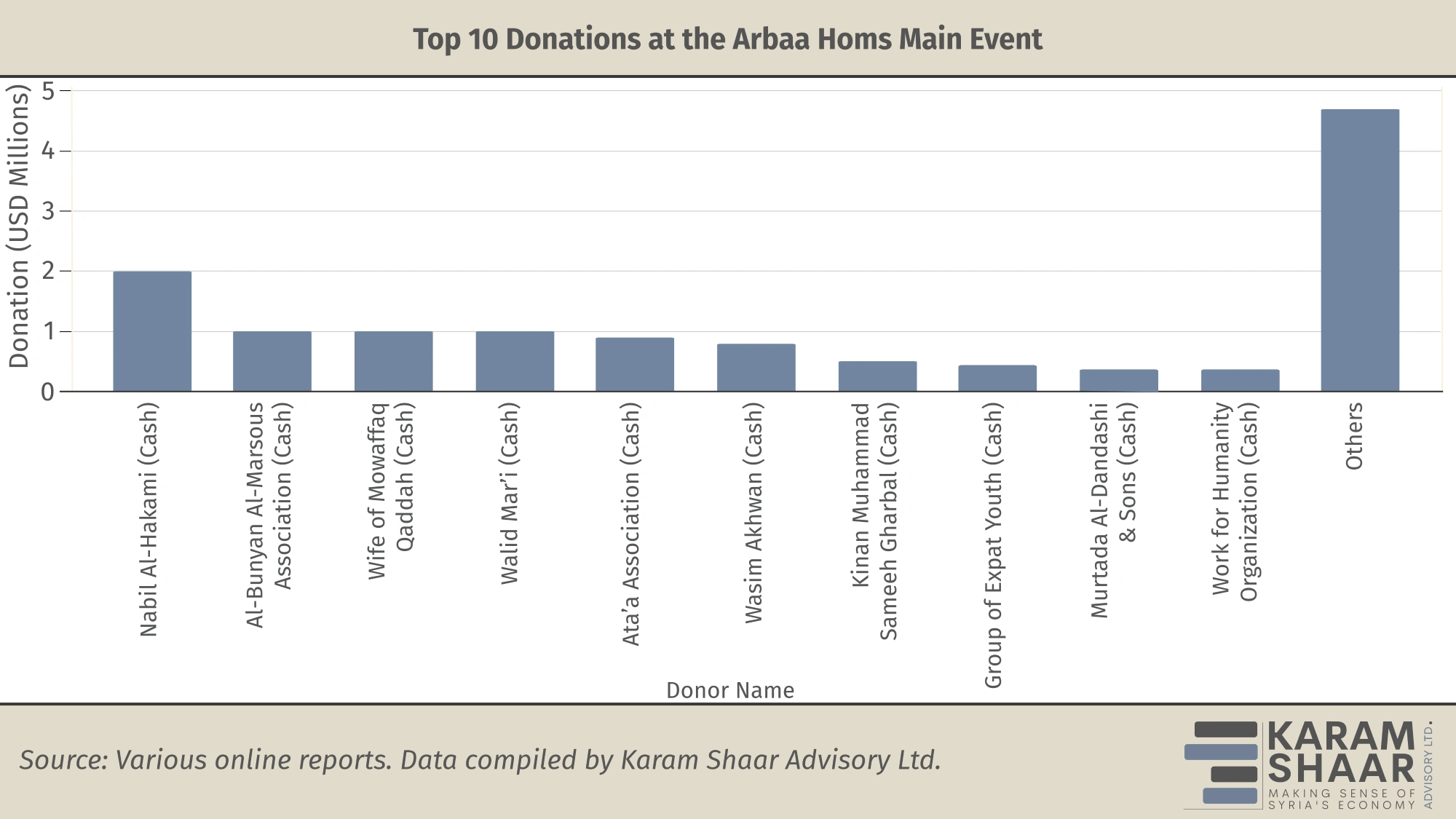

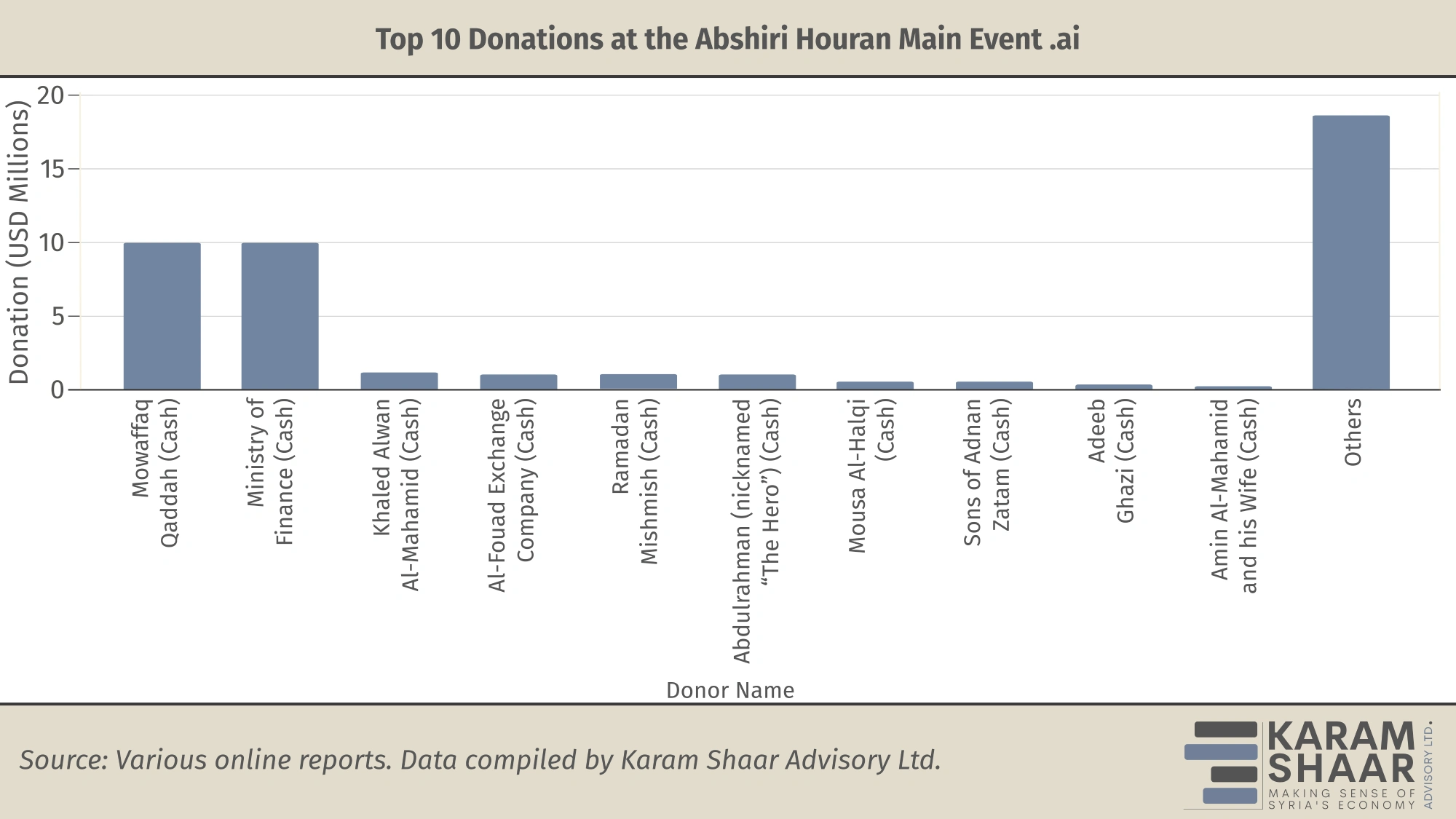

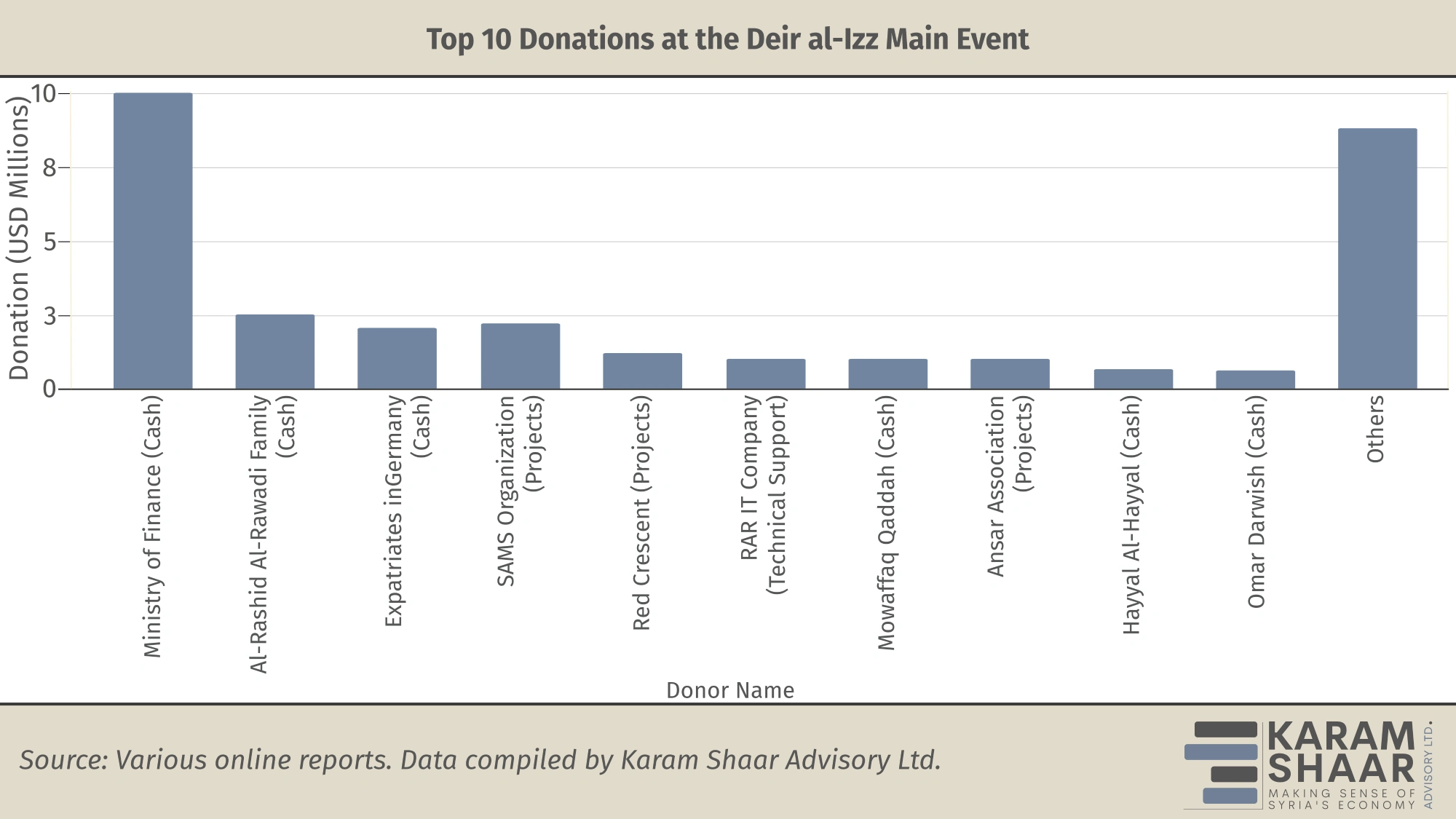

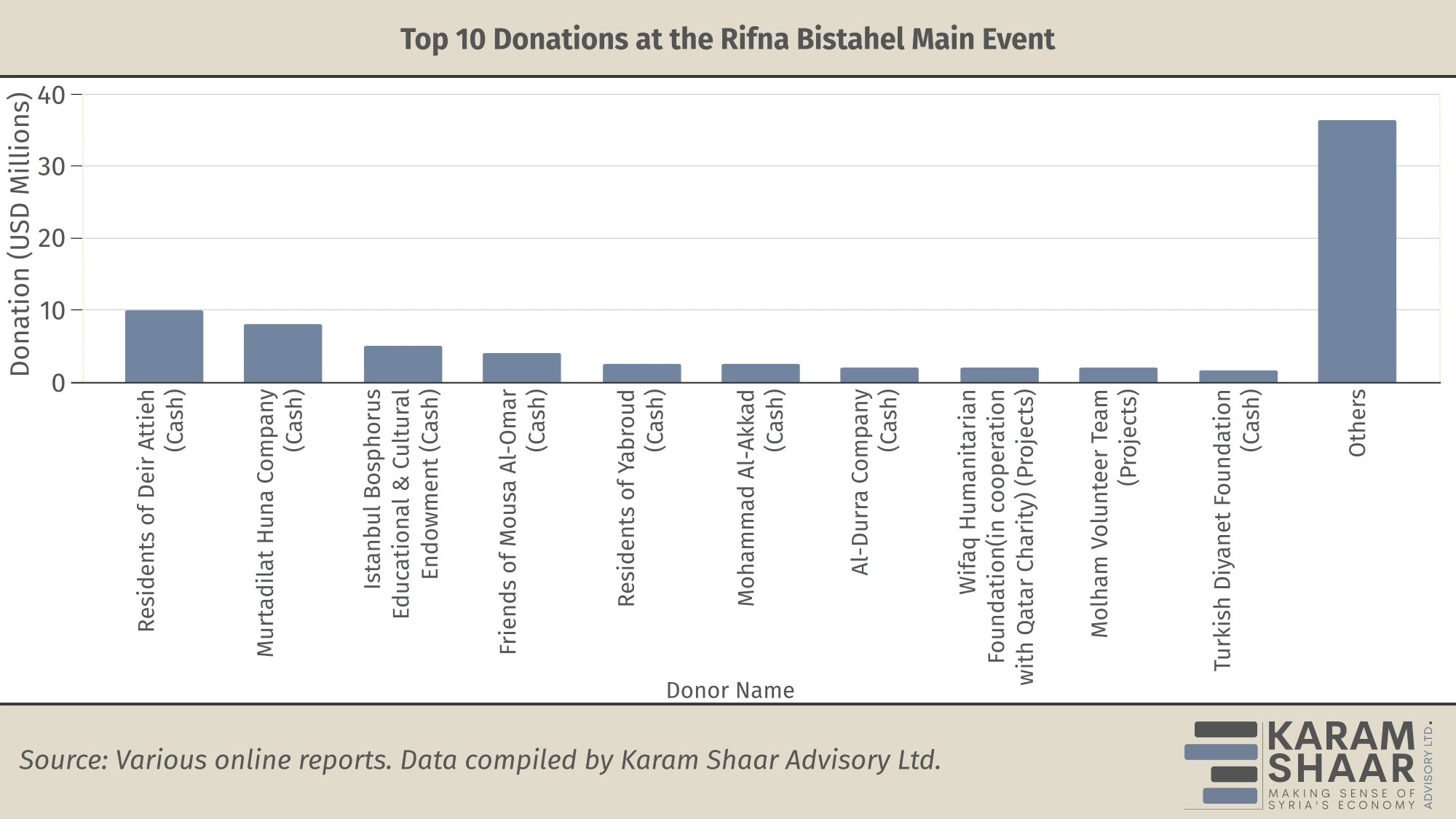

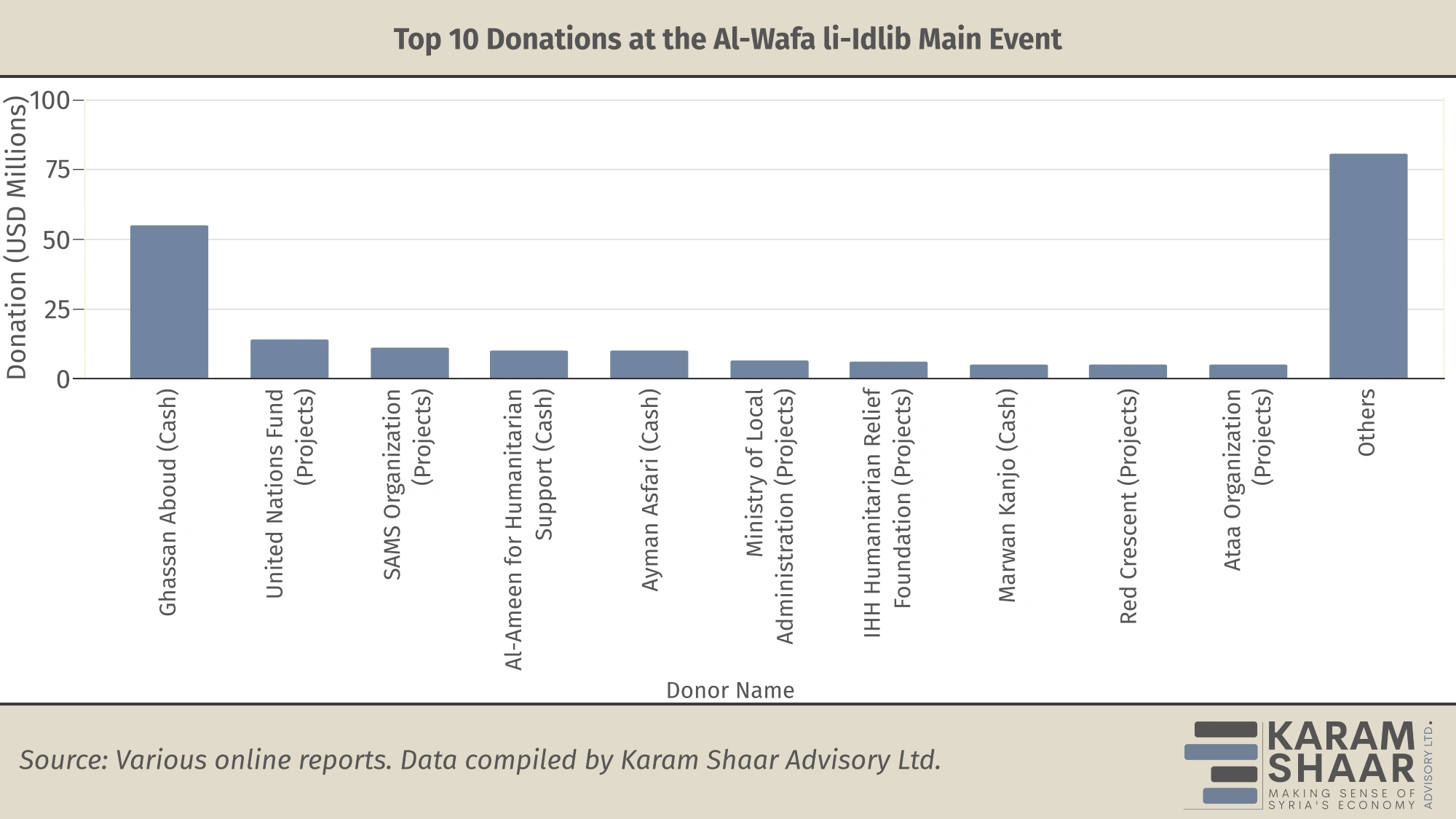

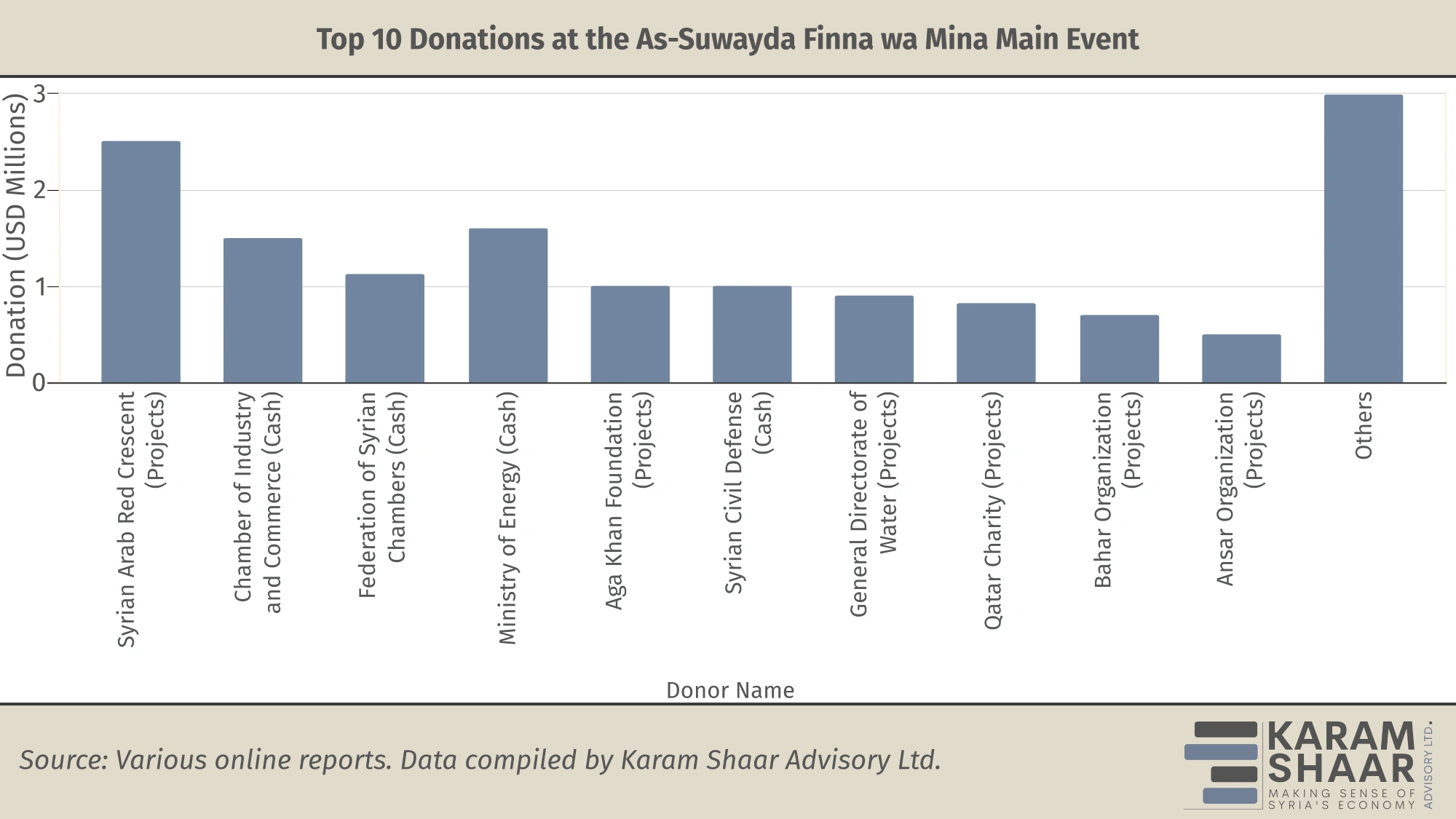

Thus emerged a culture of community solidarity, supported by networks of local and expatriate businesspeople who possess both liquidity and a desire to reinvest socially in their regions of origin. The largest donors in each campaign were typically single businessmen or groups of Syrian expatriates.

Political Economy Considerations

While these campaigns appear impressive on paper and have raised millions in aid, looking beneath the surface reveals several troubling elements.

Chief among them is that a portion of the funds pledged appears to be old money—resources already allocated to specific projects or previously spent. This creates several problems. A source from an institutional donor operating in Syria, who requested anonymity, told Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd. that the large sums announced in some fundraising campaigns, such as in Idlib, risk creating an illusion of abundance that could discourage future international commitments, even though the money itself is not new. For example, the Ministry of Finance’s USD 10 million pledge to the Abshiri Houran campaign reportedly comes from the 2025 state budget earmarked for Daraa Governorate, meaning no additional funds were actually mobilized.

Similarly, several NGOs publicly announced donations in the form of “projects” (see charts above) some of which are in fact pre-committed program funds rather than new pledges. According to our source, “all the organizations pledging millions are pledging money that has either been implemented or is close to being implemented.” The same source added that several donors have already expressed concern that some NGOs pledged funds already allocated to existing aid projects, often without prior donor approval. One donor government indicated it would review these campaigns to trace how its partners made such pledges, noting that—depending on the terms and conditions—fulfilling those pledges could prove problematic.

For domestic planners, this raises an additional concern: when funds are already earmarked for specific projects, there is little flexibility to decide how those resources should actually be used—making genuine planning nearly impossible.

This issue connects directly to the broader problem of unclear responsibility. Although these initiatives formally fall under the umbrella of community-based local development programs supervised by each city’s governorate and the Ministry of Local Administration, it remains uncertain how funds are managed and under what enforceable legal or financial framework. If the campaigns rely primarily on recycled or symbolic pledges, will organizers implement the promised projects, or are these initiatives serving more as public-relations exercises than operational programs? Without clear management and reporting, the line between genuine reconstruction and performative generosity becomes blurred.

Transparency, accountability, and sustainability mechanisms are also lacking. No auditing systems, public oversight channels, or credible follow-up mechanisms have been publicly announced. Without transparent reporting, trust could erode quickly, and donations risk being politicized or diverted toward narrow interests.

The Way Forward

The rise of community-led financing in Syria is, in many ways, admirable—a reminder that local solidarity can serve as a genuine driver of economic recovery when public resources are scarce. Yet to sustain this momentum, these initiatives would benefit from structured support to strengthen their transparency and governance. International donors, though rightly concerned by these fundraisers, should aim to engage by helping them evolve into accountable, community-driven mechanisms. After more than a decade of dependence on international aid, allowing Syrians to take ownership of their recovery could help rebuild social trust and collective agency—though this does not mean they no longer need external assistance. Rather, it suggests that aid should increasingly work with Syrians, not merely for them.

To achieve this, a shift in approach is needed: from emergency relief to institution-building. Instead of focusing solely on disbursement, partners could help design frameworks that standardize transparency, auditing, and community consultation across campaigns. Supporting local oversight bodies, training municipal staff, and promoting shared data platforms would create a stronger foundation for trust, making each campaign part of a coherent national effort rather than an isolated act of generosity.

Equally important is the need to professionalize the link between these community campaigns and municipal or national planning processes. Technical assistance in project design, monitoring, and procurement could ensure that funds are directed toward genuine local priorities rather than symbolic or politically expedient projects. Quiet investment in these coordination mechanisms would transform spontaneous solidarity into a more durable model for reconstruction.

Finally, supporting local intermediaries—such as universities, chambers of commerce, or civil society organizations—can anchor community financing within a broader ecosystem of accountability and skill-building. Such targeted, low-visibility engagement would empower Syrians to manage their own recovery while aligning grassroots generosity with wider reconstruction and stabilization goals.