International Oil Companies: The Return to Syria

- Issue 11

Following more than a decade of international isolation and armed conflict, Syria’s oil and gas sector is beginning to recover. This article builds on our previous examination of the sector’s governance framework to explore recent developments, legal shifts, macroeconomic consequences, and the strategic implications of renewed foreign interest.

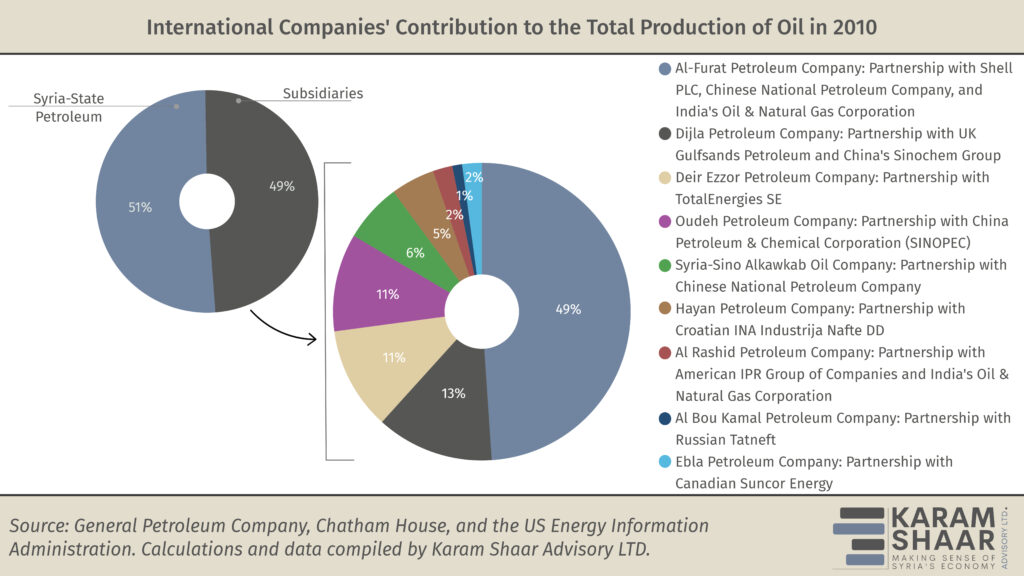

Since the 1950s, the sector’s growth has been strongly supported by international companies, whose advanced technologies and practices enhanced exploration and production. Legally, investment has been structured around joint ventures between state-owned entities and foreign firms operating through subsidiaries. By 2010, international companies accounted for about half of oil production, underscoring their substantial role.

From 2011 onward, however, international sanctions were imposed by the US, EU, and UK, among others. They targeted public entities such as the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources and the General Petroleum Company, while also restricting dealings with the Central Bank of Syria. These sanctions, combined with deteriorated security conditions, pushed most foreign firms to withdraw or suspend operations under force majeure. Although local courts allowed joint ventures to continue with local staff after foreign withdrawals, the legacy of suspended partnerships still generates legal and financial complications.

After the collapse of the Assad regime, however, policy shifts in Western capitals transformed the operating environment. In May, the US Treasury issued General License 25, granting immediate sanctions relief. The State Department also introduced a 180-day waiver from sanctions imposed under the Caesar Act. That same month, the EU formally lifted all economic sanctions and removed 24 entities from its sanctions list, including oil production and refining companies. Earlier in March, the UK had also eased restrictions on energy services and lifted the asset freeze on several local oil companies.

Syrian officials welcomed the lifting of sanctions on key sectors. The caretaker Energy Minister called it “an important step that will enable us to accelerate the development of the oil sector, rehabilitate infrastructure, and build national capacities in a way that enhances the independence and sustainability of this vital sector.”

In response, multiple governments expressed interest in reviving Syria’s oil and gas sector. Türkiye moved first, announcing plans to rehabilitate and equip the Kilis–Aleppo natural gas pipeline, as well as develop additional transit routes linking Syrian oil and gas resources to Türkiye’s export terminals.

Azerbaijan also emerged as a key player. At the Antalya Diplomacy Forum in April, Interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa met with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev to discuss cooperation, including the involvement of the State Oil Company of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SOCAR). This materialized later in August with the start of gas deliveries from Azerbaijan to Syria via Türkiye, funded by Qatar.

Iraq followed suit. In April, a delegation visited Damascus to explore reopening the Kirkuk–Baniyas pipeline, damaged in 2003 and estimated to cost USD 300–600 million to repair. The Syrian Energy Minister then visited Baghdad in August to continue discussions.

In May, Energy Minister Mohammad al-Bashir and Saudi Arabia’s Deputy Minister of Industry and Mineral Resources discussed joint investment opportunities and regional energy cooperation. Around the same time, reports surfaced that President Sharaa had offered US companies privileged access to Syria’s energy sector to ease sanctions and improve ties with Washington. A confidential plan revealed in May outlined a proposed joint venture, SyriUS Energy, between Syrian authorities and US firms. The five-phase strategy involves oil field security and infrastructure repair, supply restoration, creating a national oil company, ensuring transparent governance, and enabling exports through regional networks.

The proposed company would be listed in the US stock market and 30%-owned by a Syrian sovereign wealth fund. The plan, submitted by the CEO of Argent Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), may have limited success, as many of Syria’s current oil blocks are already claimed by companies forced to suspend operations because of conflict and sanctions.

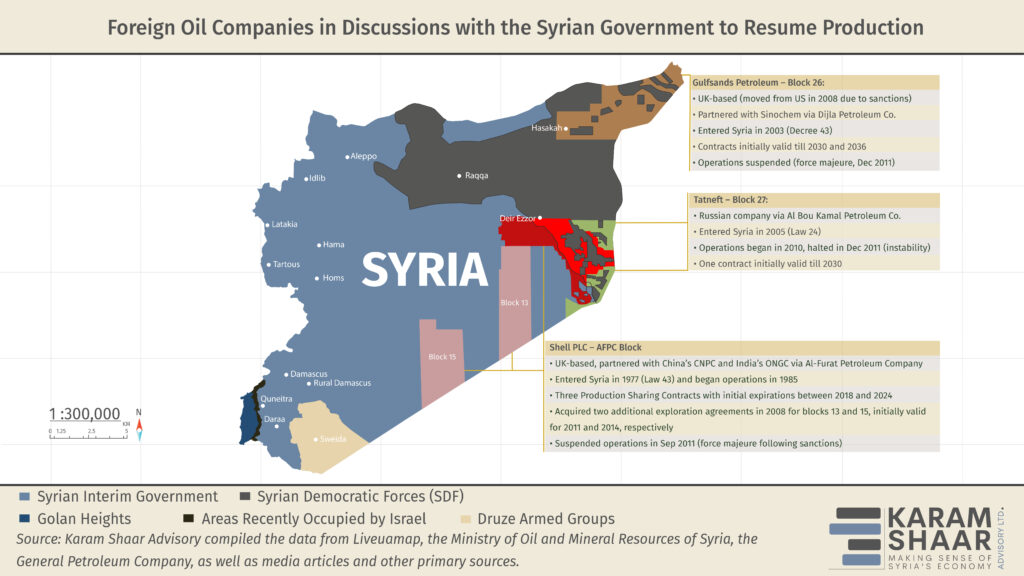

In February, then-Minister of Oil and Mineral Resources Ghiath Diab publicly called on previously operating oil companies to return and revitalize the sector, stressing that natural resources and national determination would be key to restoring Syria’s position in the energy landscape despite prevailing challenges. As part of this effort, Damascus formally invited Russia’s Tatneft to resume activity in Block 27 near the Iraqi border, where it had operated between 2005 and the end of 2011.

Although Russia has scaled back its military presence in the country since the fall of Assad, the new administration appears committed to sustaining—and perhaps expanding—Russian economic engagement. During his visit to Moscow, described by Damascus as “historic,” the Syrian Foreign Minister emphasized the country’s intention to reset relations with Russia and foster a balanced partnership.

Gulfsands Petroleum, a UK-based company that held production rights in Block 26 (northeastern Syria) before declaring force majeure in 2011, has been among the first to take steps toward return. The company maintains a strategic interest in the Syrian market and has closely monitored unlawful production activities in Block 26 throughout the conflict.

In 2023, before Assad’s collapse, Gulfsands sought to resume operations in Syria, launching “Project Hope,” a proposed “humanitarian and economic stimulus” initiative designed to revive international energy operations in northeast Syria. It would have let the company restart operations and channel oil profits into an internationally administered fund to finance recovery, humanitarian, economic, and security projects across the country. The initiative was never implemented.

In May 2025, senior leadership from Gulfsands visited Syria to discuss re-entry plans with government officials. In June, the CEO confirmed the company is preparing to resume operations and is working with the new Syrian authorities to resolve issues following its force majeure declaration. On 27 August, the company visited Damascus again and met with the Minister of Energy to follow up on the possibility of resuming operations.

While early movers like Gulfsands have shown strong interest in re-engaging, such efforts reflect a unique case, as most of the company’s assets are tied to Syria. Recently, however, momentum has spread. The Minister of Energy met with Shell representatives to discuss rehabilitating Syria’s oil infrastructure and potential future cooperation, with Shell signaling willingness to explore resuming operations under suitable legal and technical conditions. By contrast, other major firms such as TotalEnergies and Suncor have not publicly expressed interest.

The return of international oil companies marks a pivotal moment in the country’s post-conflict recovery. Yet the path ahead remains complex. A major obstacle is the lack of progress on the March 2025 agreement between the central government in Damascus and the de facto authorities in oil-rich areas, the SDF, which limits central government control over oil output.

If Damascus engaged firms without SDF involvement, as evidence suggests, the moves risk resistance or delays. And the cost of return is high; infrastructure across key oil fields has suffered extensive damage and neglect, requiring not only major capital investment but also technical assessments and feasibility studies.

Meanwhile, many foreign firms still hold binding contracts and unpaid claims against the Syrian government for extracted oil—estimated at USD 800 million to 1 billion—dating back to before the suspension of operations in 2011. These claims may also extend to potential shares of production from 2011 through 2025, should settlements be reached.

Therefore, while the lifting of sanctions has created an opening, the return of large-scale international investment will depend on the new authorities’ ability to provide assurances on contract enforcement and a secure operating environment.

Before the conflict, oil contributed nearly 18 percent of GDP and a quarter of state revenue, according to IMF projections in 2010, with the state budget estimating oil revenues at about 3.3 billion USD for production of 387 thousand barrels per day (bpd). Today, output is about one-third of pre-conflict levels, with most revenue bypassing the treasury through SDF affiliates.

If the central government in Damascus were to regain control, annual revenues could reach around 1.1 billion USD, 1making oil the largest single source of revenue, with total state income down to nearly 2 billion USD annually (excluding borrowing), according to figures reviewed by Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd.

1 …neglecting the slight decrease in global oil prices since 2010, possible revisions to production-sharing contracts, changes in government royalties, and regardless of any revenue-sharing arrangements with Kurdish forces.