The Revival of Syria’s Oil Pipeline Network

- Issue 16

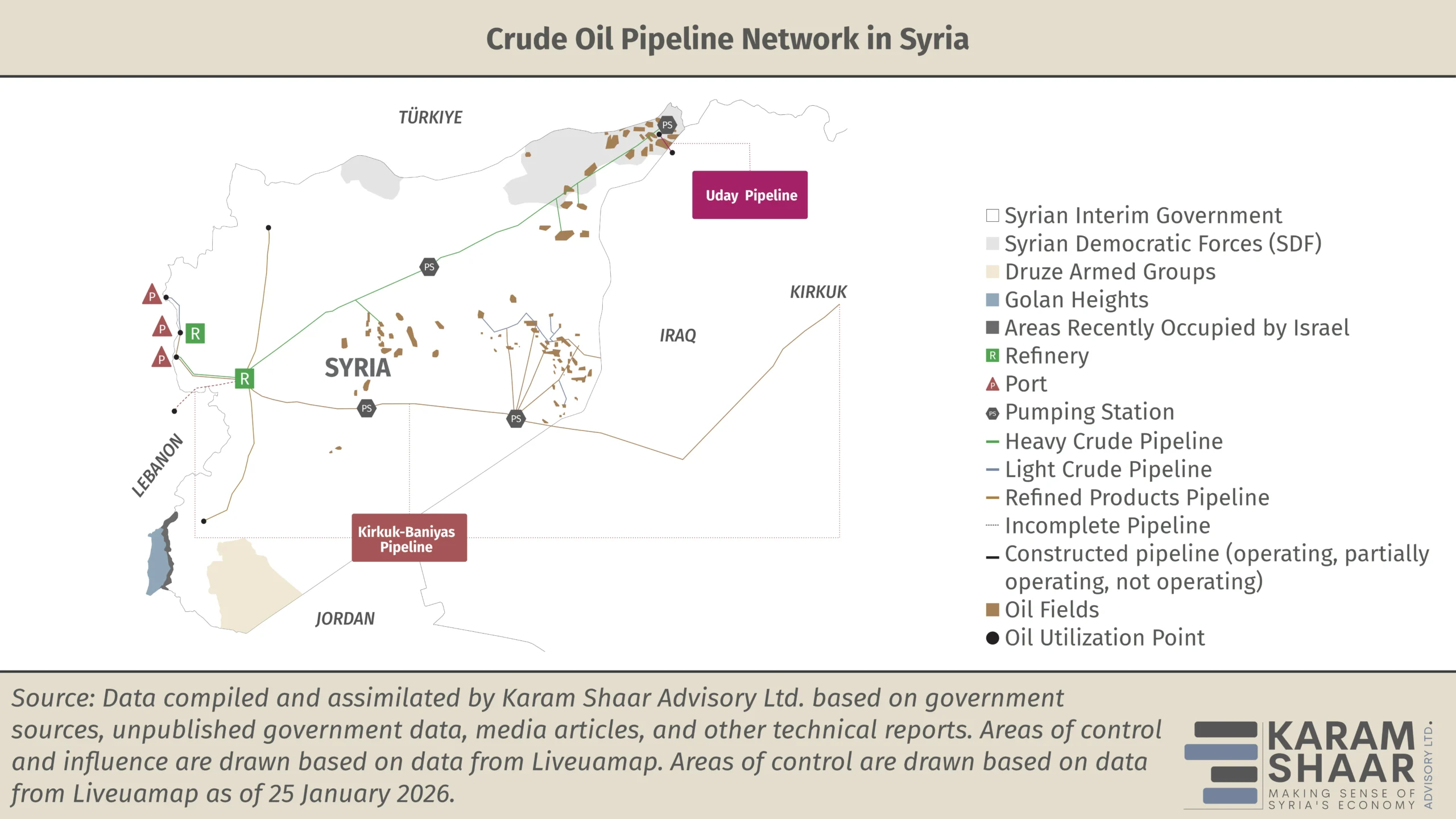

Building on our previous article on Syria’s gas pipeline network, oil pipelines form the backbone of the country’s petroleum sector. Before 2011, Syria was a net oil producer, with pipelines enabling crude exports through Mediterranean ports. It also served as a transit corridor for Saudi (1950–1990) and Iraqi (1952–2003) oil bound for international markets. This article reviews Syria’s domestic and regional oil networks and recent efforts to restore cross-border routes.

Years of armed conflict have inflicted catastrophic damage on this infrastructure and fragmented control over critical networks. More than 1,000 km of oil and gas pipelines in northeastern Syria alone are now estimated to require complete replacement rather than repair. This assessment was echoed by Youssef Qabalawi, CEO of the Syrian Petroleum Company, who stated that the nationwide pipeline network is severely deteriorated, lacks maintenance, and contains chemical deposits and salts.

Syria’s domestic oil pipeline system, developed primarily in the late 20th century, connects scattered production fields across the country’s eastern and central regions to the Homs and Baniyas refineries and supports exports through the Baniyas and Tartous offshore terminals.

The heavy oil system runs from Tal Adas in the Rumeilan fields to Tartous, stretching about 663 km and designed for a capacity of 300 thousand barrels per day (bpd). The light oil system links Deir Ezzor to Baniyas across a total network of about 2,000 km, of which 1,185 km were operational before the conflict. Four main gas-turbine pumping stations operate on the light crude system, while nine electrically powered stations serve the heavy crude system. Years of conflict have left much of this infrastructure destroyed.

Syria’s oil production stood at 387,000 bpd in 2010, of which about 40 percent was exported mainly to Europe. Years of conflict and sanctions eliminated exports, though fragmentation later allowed Kurdish-controlled areas to trade with Iraqi Kurdistan through the “Uday” pipeline.

A previous Syria in Figures article on oil supplies in 2025 showed that government-controlled areas now rely almost entirely on imports. This has pushed Damascus to seek more stable and cost-efficient means of supply, including pipelines, where Syria is currently looking for opportunities. Historically, Syria’s Mediterranean terminals positioned it as a transit corridor, with two major lines crossing its territory: the Trans-Arabian pipeline (Tapline) and the Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline, both now dormant or abandoned.

The Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline, completed in 1952, is Syria’s most important transit asset, linking Iraq’s Kirkuk fields to the port of Baniyas. The 800 km line, with a capacity of 300,000 bpd, was suspended in 1956–1957 during the Suez crisis, again from 1982 to 2000 when Syria sided with Iran during the Iran–Iraq War, and finally in 2003 following the US invasion of Iraq and sabotage that rendered it inoperative, leaving it dormant for more than two decades.

During this period, efforts to revive the pipeline intermittently resumed. In 2007, Stroytransgaz, a major Russian oil infrastructure firm, opened discussions with Iraqi authorities, though planned repairs were postponed in 2009. Reports later suggested the US was opposing the project to increase economic pressure on Damascus. In 2010, Syrian and Iraqi authorities signed an agreement to build two new Kirkuk-Baniyas pipelines, one for light crude (1.25 million bpd) and one for heavier crude (1.5 million bpd). A year later, both sides met again to discuss restoring the original single line.

The pipeline fell off the agenda during the early years of the conflict. In mid-2019, however, news reported that Iran had revived a proposal for alternative export routes, either by building a new 1,000 km line through Iraq or rehabilitating the Kirkuk-Baniyas route at Iran’s expense. The project, with a planned capacity of 1.25 million bpd, was reportedly destined for the Lebanese coast. Russia later supported the initiative and held meetings in Baghdad to advance it. No action followed until Iraqi Prime Minister Mohamad Shia’ al-Sudani visited Damascus in July 2023 to discuss reopening the pipeline. Iraq’s government spokesman later confirmed Baghdad’s readiness to engage.

The collapse of Syria’s regime in December 2024 reignited momentum. Between April and November 2025, senior Iraqi and Syrian officials—including Iraq’s National Intelligence Service Director and Syria’s Energy Minister—met to address security concerns and pipeline rehabilitation. Talks progressed to the ministerial level, exploring potential extensions to Lebanon. By November, both governments agreed to hire an international consultant to assess the infrastructure and feasibility of reactivation.

Joint technical committees from both countries are conducting engineering studies to determine whether to restore the existing route or construct an alternative. Preliminary estimates suggest reconstruction costs could exceed USD 4.5 billion and take around 36 months. By mid-December 2025, Syria’s Deputy Energy Minister Ghiath Diab emphasized that Damascus and Baghdad were advancing plans for a dual pipeline with a capacity of up to 1.5 million bpd, including new pumping stations and a potentially rerouted section in Deir Ezzor.

Syrian Petroleum Company CEO Qabalawi recently stated that the main pipeline requires full reconstruction. Pumping stations were hit by missile strikes, and he described the project as a top priority. Despite the cost, he noted interest from development banks, including in Saudi Arabia, and said Iraq is also keen. Construction could take about two years if work proceeds simultaneously from east and west.

On 17–18 January 2026, government forces regained control of oil resources in northeast Syria from the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) under a comprehensive 14-point ceasefire agreement. The deal transferred all oil and gas fields and related infrastructure in Deir Ezzor and Raqqa to Damascus, marking the first time in over a decade that the government controls most of Syria’s hydrocarbon assets. For international companies, this consolidation enables coherent permitting, contract enforcement, and revenue collection for cross-border pipeline projects.

For Damascus, the Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline offers a cost-efficient way to secure crude for domestic refining. Government-held Syria currently consumes about 120,000 bpd but produces only 8,000 bpd. The recently acquired northeastern fields produce roughly 31,700 bpd in Deir Ezzor and about 2,000 bpd in Raqqa, according to field data collected by Karam Shaar Advisory Limited. This leaves Damascus dependent on imports primarily from Russia. Russian crude has been arriving via sanctioned tankers operating shadow fleets, exposing Syria to secondary sanctions and high transport costs. Iraqi crude via Kirkuk-Baniyas would reduce costs, eliminate sanctions exposure, and—at a potential capacity of 1.5 million bpd—far exceed domestic demand, positioning Syria as a transit corridor to Lebanese and international ports while generating an estimated USD 200 million a year in transit revenue.

For Western policymakers, supporting the pipeline revival has strategic value beyond energy supply. Russia maintains asymmetric leverage over Damascus through its role as the primary oil supplier, its bases at Hmeimim and Tartous, and its potential involvement in printing Syria’s new currency. Facilitating Iraqi–Syrian energy integration would reduce Moscow’s influence without direct confrontation.

Negotiators, however, must navigate complex obstacles, including the Kurdistan Regional Government’s claims over Kirkuk oil. New legal frameworks would be required to address environmental liability, security cost-sharing, international inspection protocols, and dispute resolution mechanisms.