What Do the Compositional Changes Between the Caretaker and Interim Governments Tell Us?

- Issue 7

In our last edition of Syria in Figures, we raised what seemed like straightforward questions about Syria’s transition: Will loyalty eclipse competence? Will HTS’s dominance continue? Will the cabinet represent Syrians better?

At the time, Syria stood on the brink of a declared transition, with the cancellation of the Prime Minister role and a new constitutional framework. Amid promises of reform and inclusivity, Syria’s Interim Government (IG) was announced on 29 March, offering something new: ministers we could actually identify. Unlike the opaque Caretaker Government (CG), this cabinet features more individuals with public records and identifiable backgrounds, signaling a shift in selection criteria and an overall improvement in the notability of the ministers. So, what have we really got?

Technocratic Upgrade, with Caveats

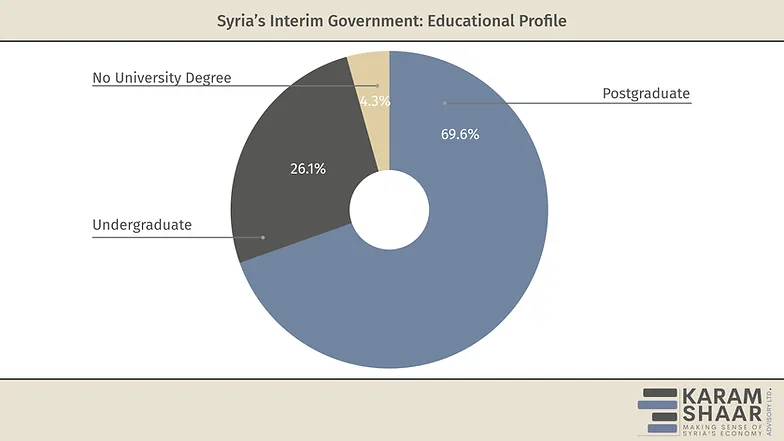

The new IG is notably better credentialed than its predecessor. Of its 23 ministers, 16 hold post-graduate degrees, many from prestigious institutions in Europe and North America, and several have held senior roles, either in Syria or abroad.

In contrast, the CG was composed largely of ministers with basic undergraduate qualifications from Syrian universities and minimal experience in formal state institutions. Some profiles lacked even publicly available educational information.

While the new cabinet isn’t purely technocratic, it marks a clear shift toward significantly higher educational standards and more diverse institutional exposure, particularly in areas relevant to economic governance.

HTS and the Lion’s Share

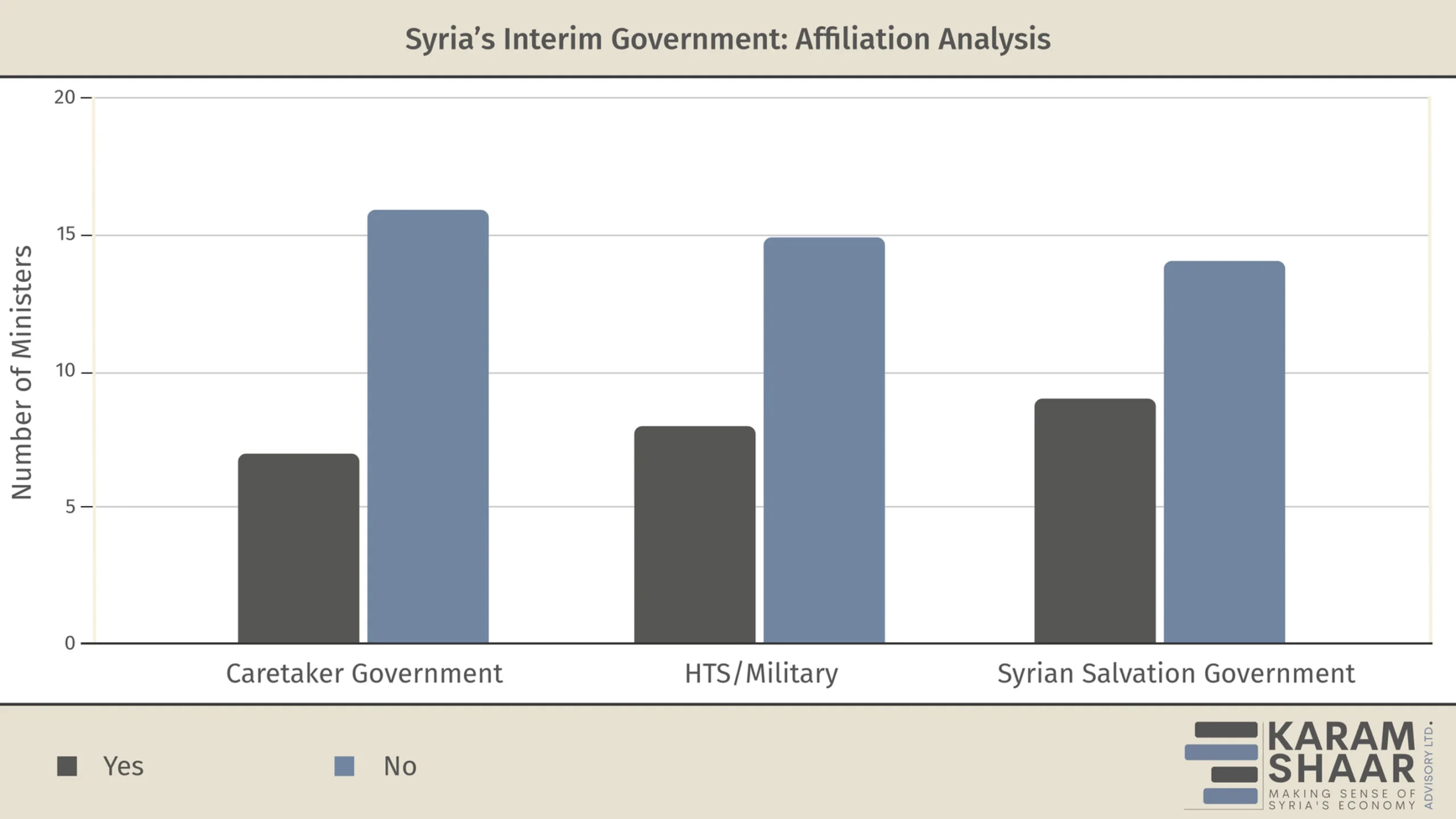

While the new IG presents a more polished and pluralistic face, its composition reveals strategic continuity beneath the surface of diversification. Nine ministers have known affiliations with the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), and eight are linked—directly or indirectly—to HTS or its military formations. These affiliations are concentrated in the most influential portfolios, including foreign affairs, defense, interior, justice, and local administration, suggesting that core power remains tightly held even as new figures are introduced.

At the same time, the cabinet marks a deliberate broadening of the leadership pool. 14 ministers have no SSG ties, and 15 are free from HTS/military affiliations. Notably, 16 of the 23 ministers did not serve in the CG, with many having backgrounds in humanitarian work, development, academia, and the private sector.

Compared to the CG, where over half (55%) of ministers were SSG-affiliated and factional ties were widespread, the new cabinet presents a more varied mix of affiliations and trajectories.

From No Women to Virtually No Women

Of the 23 ministers, only one is a woman, appointed as Minister of Social Affairs and Labour. A Christian from Damascus with a postgraduate degree in law and diplomacy, she carries international credibility. But her appointment, while symbolically significant, is confined to a traditionally “soft” portfolio, reinforcing rather than challenging entrenched ideas about women’s roles.

This isn’t just tokenism; it’s containment. In systems where ideological norms influence political appointments, women’s inclusion is typically restricted to sectors aligned with social cohesion or cultural affairs. This appointment doesn’t represent a breakthrough in gender equity but a carefully managed exception. While it’s an improvement from the all-male CG, the glass ceiling remains unbroken—just artfully reframed.

Sunni Arabs Playing a Less Dominant Role

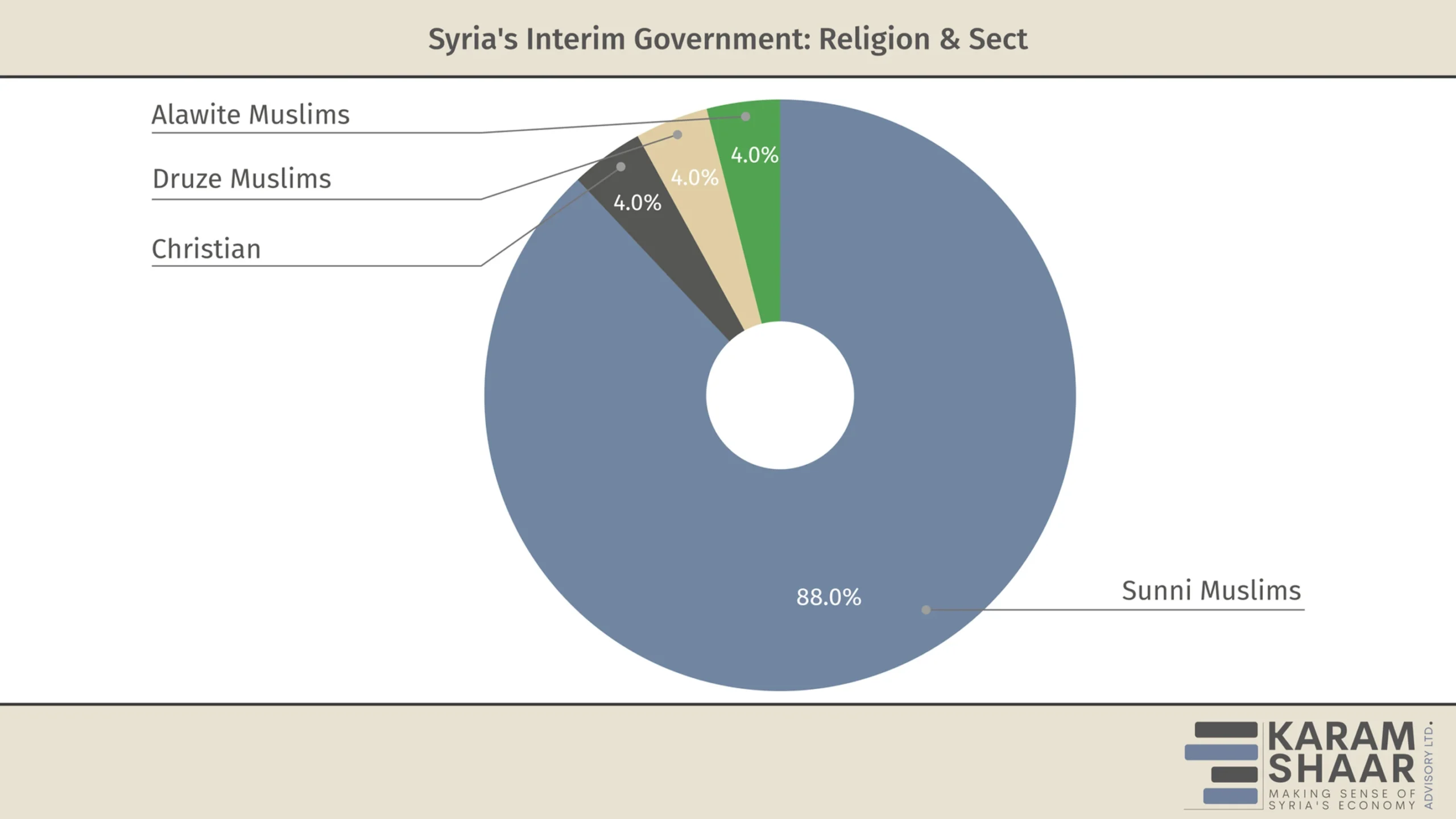

The IG is still overwhelmingly Sunni Arab Muslim, with 20 of 23 ministers identifying as Sunni. However, there are signs of cautious broadening: one Druze and one Alawite minister have been appointed, marking a modest shift from the CG, which had no sectarian diversity.

Religiously, the cabinet includes one Christian; ethnically, it remains predominantly Arab, with two Kurdish ministers reflecting a similar share of the overall population.

As the government’s sectarian and ethnic composition remains narrowly focused, the inclusion of a few minority figures seems more like a calculated gesture toward inclusivity than a true sharing of power.

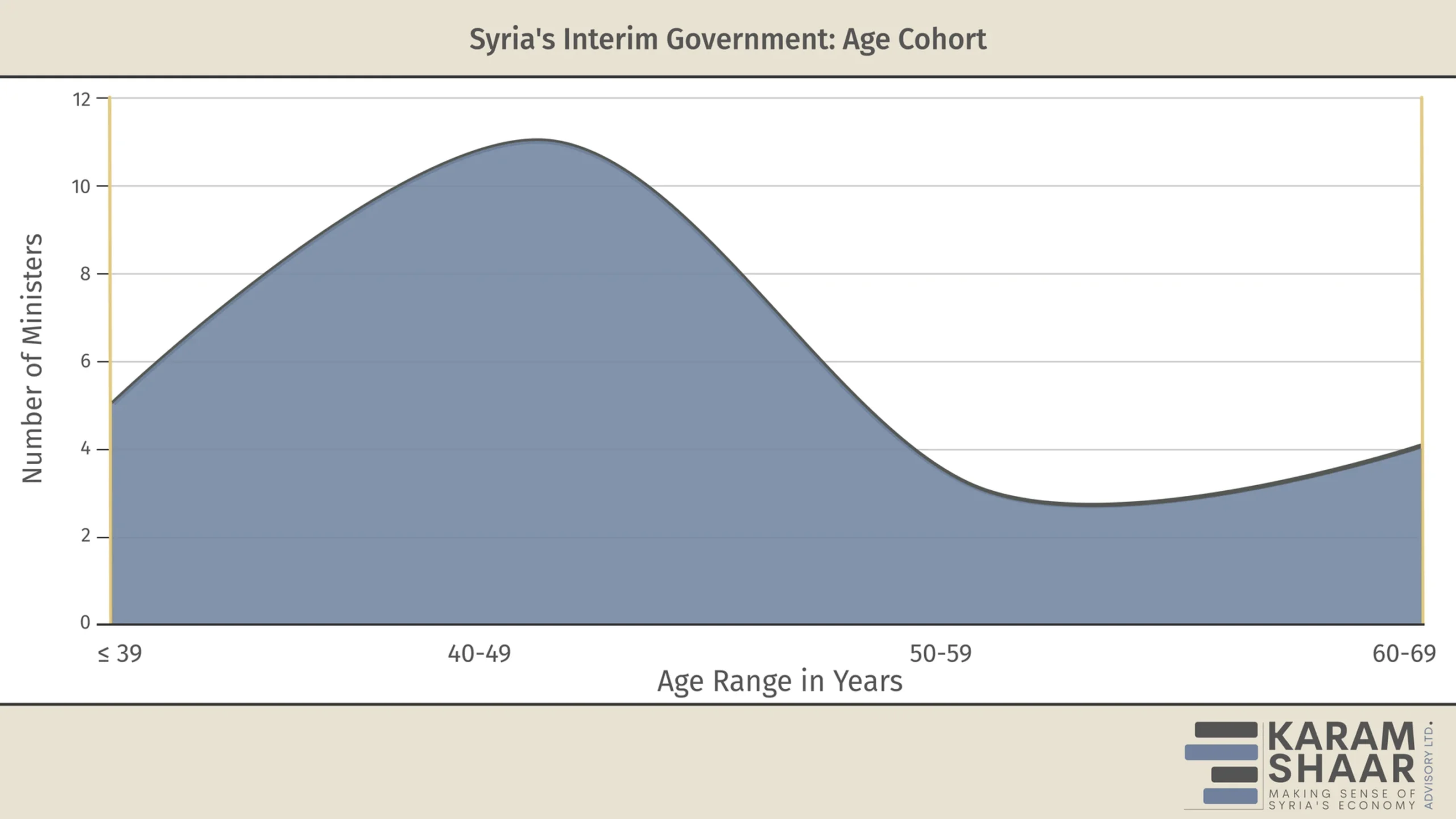

Age Distribution: Youthful Energy?

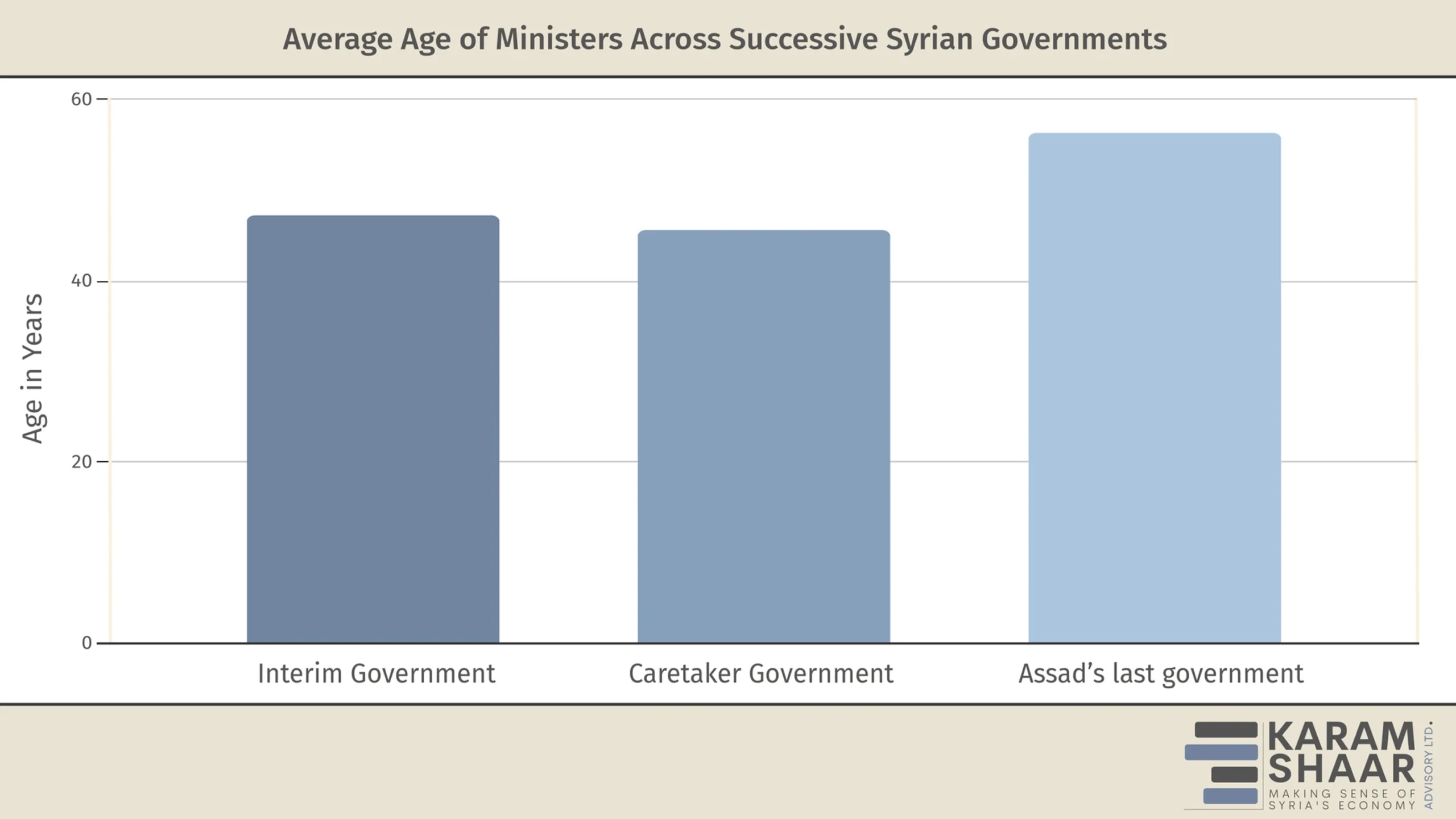

With an average age of 47.3, the IG continues the generational shift seen in the CG and remains a decade younger than Assad’s last cabinet.

However, while four ministers are in their 60s—most with prior government experience, adding institutional weight—a considerable share are relatively young and may bring fresh energy and new ideas.

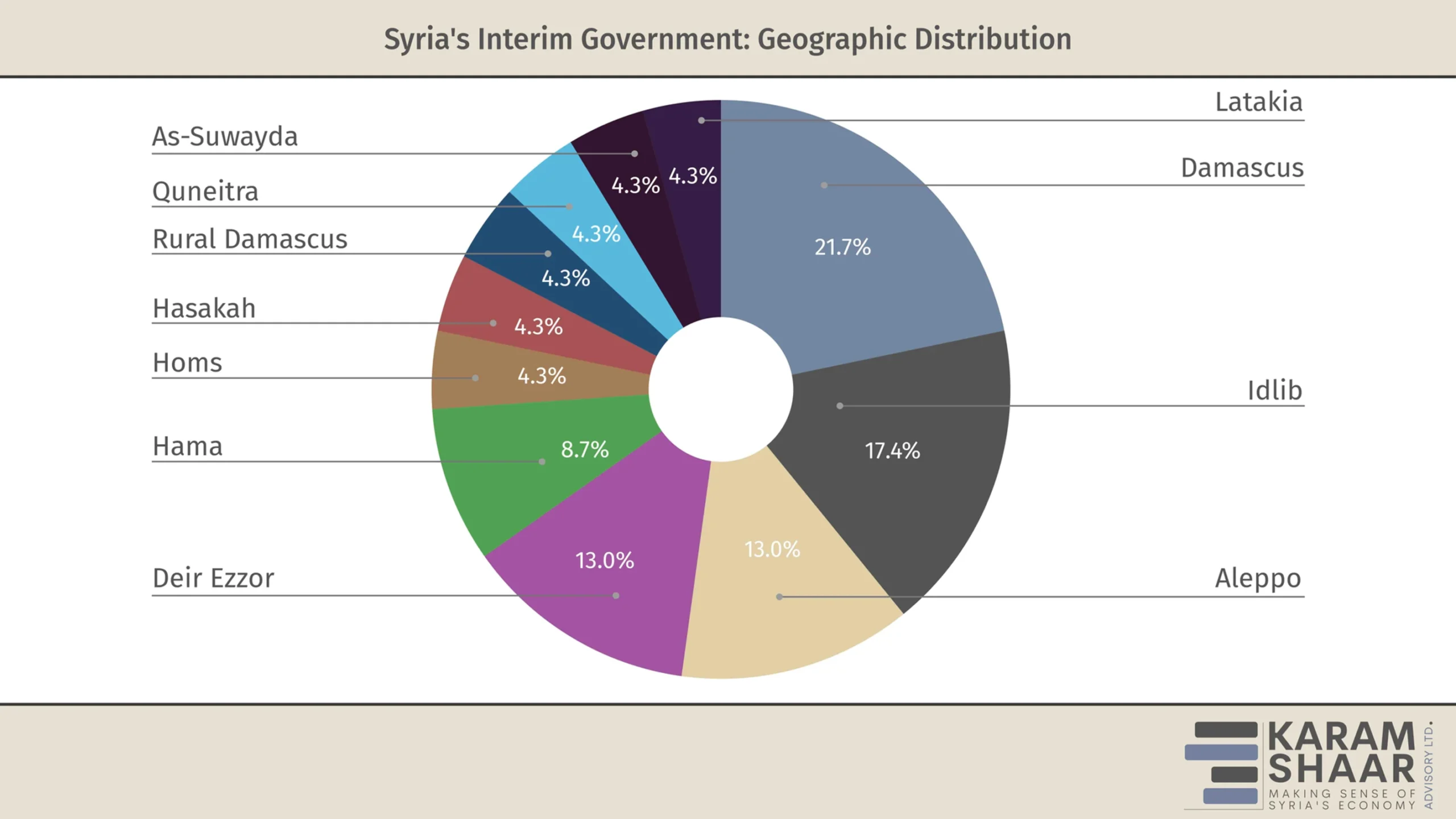

Improved Geographic Representation

The IG draws ministers from 11 governorates (only Raqqa, Daraa, and Tartous are not represented), a notable shift from the CG’s heavy concentration in former HTS areas in northwest Syria. Damascus now leads with five ministers, followed by Idlib with four, and Aleppo and Deir Ezzor with three each. This broader spread marks a clear improvement in geographic representation, and the inclusion of ministers from marginalized areas suggests a deliberate effort to counter perceptions of territorial exclusivity.

However, the center of gravity hasn’t shifted entirely. Over half of the cabinet still comes from Damascus, Idlib, and Aleppo, meaning that while the geographic footprint has expanded, power remains concentrated in familiar zones. The true test will be whether this spatial diversity translates into political pluralism.

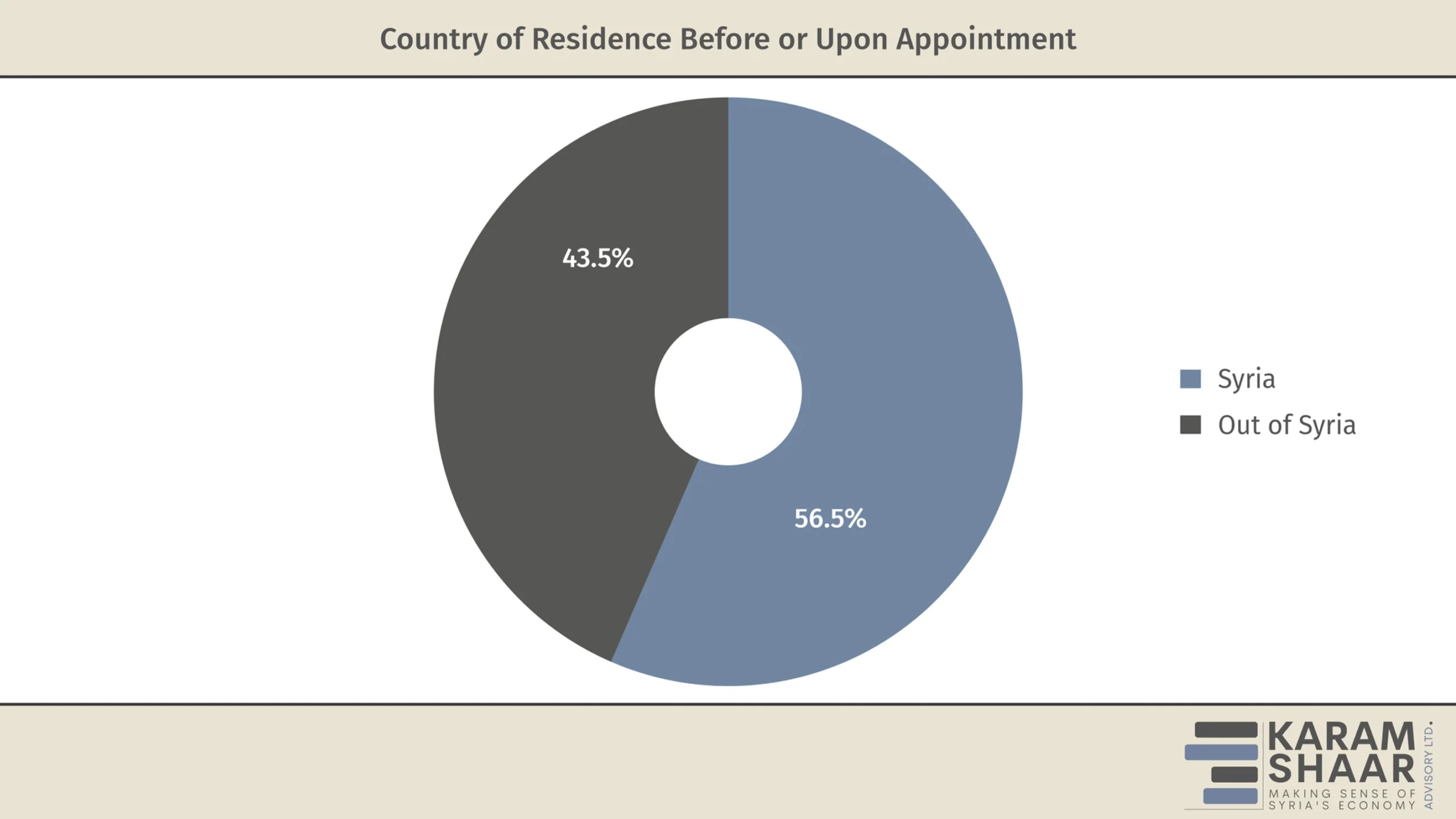

Country of Residence (Before and Upon Appointment)

One interesting aspect of the IG is that 43.5% of its ministers were residing outside Syria prior to their appointment, a composition familiar in other contexts following regime change, such as Iraq (2003), Libya (2011), and Rwanda (after the 1994 genocide).

This isn’t just diversity for show; it reflects a deliberate blending of domestic and diaspora leadership, combining grounded political actors with internationally exposed technocrats. Many of these ministers not only hold postgraduate degrees but also bring with them relationships built in embassies, think tanks, NGOs, and multilateral institutions.

However, given the strong influence of HTS-affiliated ministers, newcomers from abroad may struggle to translate their external networks into leverage. Whether their international ties will open doors or be quietly severed remains to be seen.

From another perspective, this transnational composition mirrors exile-return dynamics observed in other post-conflict contexts, but with a distinctly Syrian twist. It’s not a post-liberation elite returning en masse; rather, it’s a calculated blend of insiders and outsiders attempting to co-govern a fractured state.

So What?

The new IG appears more polished than its predecessor, with improved technocratic expertise, greater educational attainment, higher visibility, broader geographic and sectarian representation, and a high share of ministers from the diaspora. Many appointees bring the sheen of diplomacy, academia, or international NGOs, contrasting sharply with the insular CG. However, much remains unchanged: HTS and SSG-linked figures still dominate core ministries, and gender inclusion is largely symbolic. So, while the cast and tone have shifted, the fundamental structure and control remain familiar. Whether this blend is a genuine step toward inclusivity will depend on how the team will work together; only time will tell.