Powering the Recovery: the Electricity Sector at a Crossroads

- Issue 9

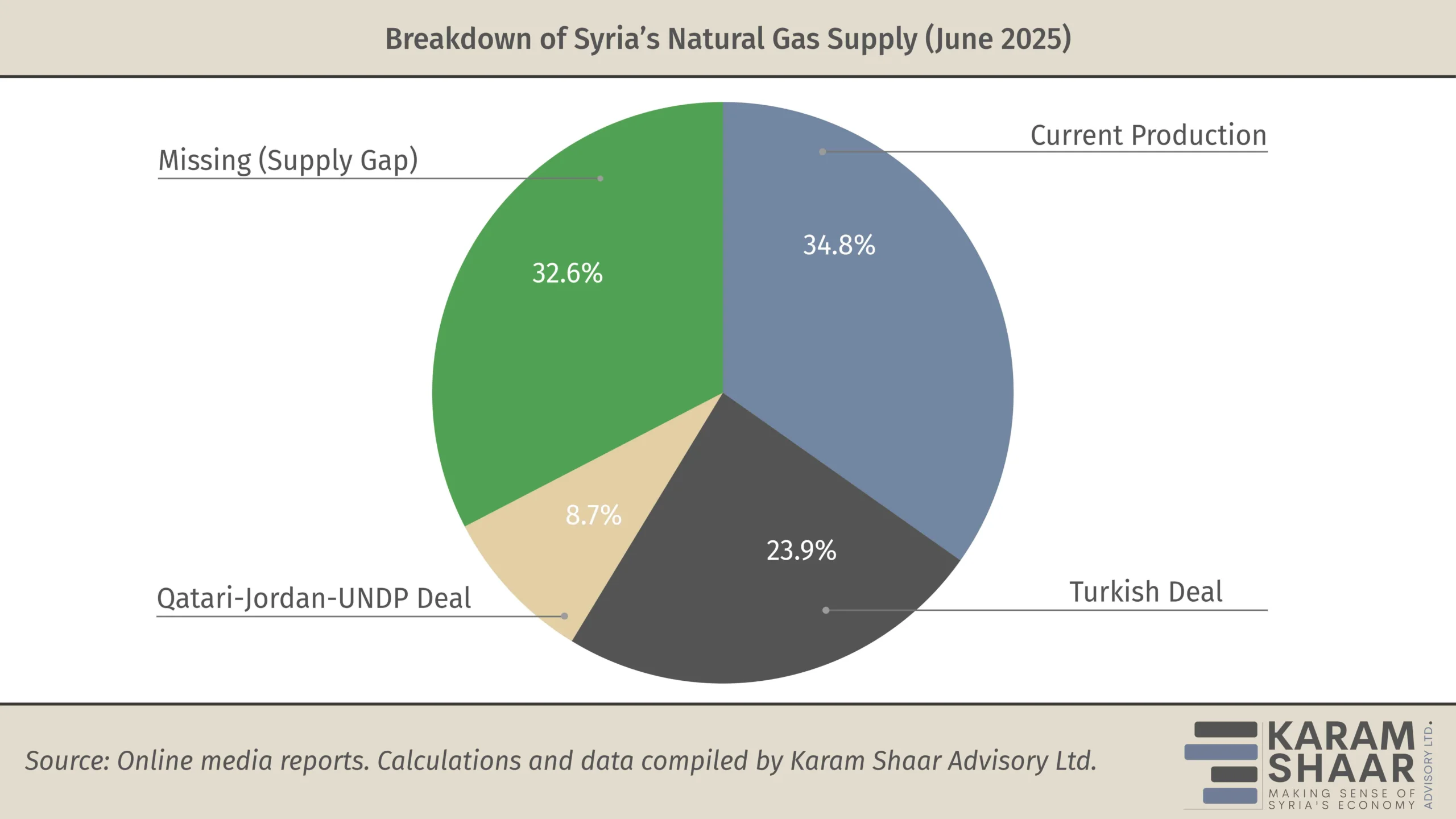

Six months after Assad’s fall, Syria’s public power output remains stuck at 1,600 megawatts (MW) per day. But a patchwork of emergency repairs, foreign-backed plans, and strategic investments is beginning to lay the groundwork for broader recovery. New gas deals with Qatar and Türkiye could double current output, supplying one-third of daily gas needs.

Domestic electricity production dropped to just 12,900 gigawatt hours (GWh) in 2023, down from nearly 49,000 GWh before the conflict. More than 30% is lost in transmission and distribution, leaving most people with only a few hours of power per day. Current output stands at less than one-fifth of pre-war levels—1,600 MW today versus 9,500 MW in 2010. (As noted in a previous edition of Syria in Figures, estimates of current capacity, assuming full fuel supply, vary widely.) The energy shortfall continues to severely constrain economic recovery.

The Interim Government (IG) has made the recovery of the electricity sector a top priority. Yet for years, international sanctions and overcompliance made investment nearly impossible. The US Caesar Act, in particular, discouraged third-country entities from engaging in “significant transactions,” effectively preventing foreign participation in infrastructure projects. That began to shift in early 2025, when the US issued General License 24 and the EU suspended key sanctions.

Italy and Germany were among the first to act. In January 2025, Italian officials and representatives from Ansaldo Energia visited the Deir Ali power station, Syria’s largest, and expressed readiness to assist with repairs and spare parts. Germany followed suit: after EU-wide easing, Special Envoy Stefan Schneck confirmed that Siemens would begin work on another section of the same plant with a capacity of up to 1,500 MW.

Regional actors also moved to support the sector. In January, Syria’s General Organisation for Electricity Transmission and Distribution announced that two electricity-generating ships from Türkiye and Qatar, expected to add 800 MW, were en route. Some reports suggested the ships had been dispatched following US sanctions relief, but no evidence of their arrival or integration into the grid has emerged. In parallel, efforts were made to revive energy connectivity and imports from Jordan and Egypt via restored pre-war infrastructure.

The turning point came in May 2025, when the EU lifted most sectoral sanctions and the US expanded relief via the issuance of General License 25 and a 180-day suspension of the Caesar Act. This cleared the way for a USD 7 billion Memorandum of Understanding with a consortium led by Qatar’s UCC Holding, in partnership with Türkiye’s Kalyon and Cengiz Enerji and with US-based Power International. The deal includes the construction of four combined-cycle gas turbine power plants (totaling 4,000 MW) and a 1,000 MW solar facility in the south, nearly tripling current output. On 13 June 2025, UCC secured sites at Deir Ezzor’s al-Taym complex for a 750 MW plant, a 1 GW solar park, and the upgrade of three substations.

Not A Straightforward Recovery

Despite high-profile deals and renewed international interest, recovery of the electricity sector is far from assured. The IG inherited deep-rooted structural and institutional challenges that continue to hinder progress.

First, while sanctions relief by the US, the EU, and the UK has reopened the door to foreign engagement, the financial architecture behind large-scale projects remains fragile. Syrian banks remain disconnected from the global financial system, making fuel procurement and project financing difficult. Some banking channels still exist (e.g., UNDP funded power plant rehabilitation projects before the regime’s fall), but it is unclear whether such channels are now accessible to private actors. Eased sanctions, however, may gradually improve the situation.

Second, fuel shortages persist. Many thermal power plants remain idle due to a lack of oil and gas; domestic production has collapsed and key fields lie outside government control. The IG’s immediate priority is to secure enough fuel, something the Assad regime consistently failed to do without external support. In March 2025, the Caretaker Minister of Energy stated that meeting daily existing power plant needs would require about 23 million cubic meters of gas and 5,000 tonnes of fuel oil.

To help close this gap, Qatar and Türkiye have pledged gas supplies. Under a deal signed by the Qatar Fund for Development and Jordan’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, with UNDP serving as facilitator, Qatar would supply enough gas to generate 400 MW via the Arab Gas Pipeline from Aqaba, or roughly 2 million cubic meters per day (cmd). Meanwhile, Türkiye has committed to supplying 5.5 million cmd via the recently rehabilitated Kilis–Aleppo pipeline beginning in early June, enough to generate 1,200 to 1,300 MW.

Combined, the two deals total 7.5 million cmd, roughly one-third of daily gas needs. When added to the 8 million cmd produced locally, total available supply now stands at 15.5 million cmd, or 67% of daily requirements. In terms of output, the deals are expected to raise generation from 1,600 MW to 3,200 MW.

As of this writing, the Turkish deal’s implementation and financing remain uncertain. Based on official figures, gas requirements to produce 1 MW vary between 4,390 cmd (Turkish figures) and 5,000 cmd (Qatari figures). Using current gas prices the Qatari contribution could be valued at USD 95.6 million per year, while the Turkish commitment could reach USD 262.1 million.

Third, the national grid is severely degraded. Years of conflict have damaged or destroyed much of the transmission and distribution infrastructure. Technical losses remain high, and theft is common in some areas, limiting the effectiveness of increased generation. Without parallel investments in the grid, added capacity will not reliably reach consumers. According to unpublished government figures accessed by Karam Shaar Advisory Ltd., restoring the grid will require an estimated USD 1.5 billion and at least five years.

Finally, concerns are growing that the sector has become entangled in politics and potential corruption. The company heads of UCC Holding, the lead partner in the flagship recovery deal, are currently at the center of a legal case in the UK. Moutaz and Ramez al-Khayyat have been accused of financing terrorism by supporting the Al-Nusra Front. (The Front, once headed by now-Interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa, later became Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and was recently dissolved.) Their apparent proximity to the new leadership raises concerns about transparency in the award process, which could undermine public trust and discourage broader investment.