Syria’s Economy a Year into Assad’s Downfall: The Good, the Bad, and Ugly

- Issue 15

Karam Shaar

Post-conflict power transitions are inherently messy; one year is far too short to fully disentangle signal from noise. That said, while Syria’s economic end state remains uncertain, the direction of travel is becoming clearer.

The Good

Unlike many pessimistic predictions, I believe the economy is on a strong recovery trajectory. It is largely a question of pace, although the 1% forecast from the World Bank already appears wildly pessimistic. Misgovernance, a fragile security situation, and the persistent fragmentation and disregard for regulatory frameworks are more than offset by multiple positive factors. Chief among these is the return of over 1.2 million refugees, along with an unknown number of non-refugee returnees, myself included. This alone constitutes more than 5% of the pre-collapse population—people who consume, seek shelter, and potentially take, albeit often tentative, steps toward investment.

One might argue that this boosts headline growth without necessarily improving prosperity when measured in per-capita terms. Not quite. The recovery trajectory is also driven by other factors, including the removal of hurdles to international trade and domestic trade between the northwest and areas formerly held by the Assad regime; memoranda of understanding (MoUs) that are expected to bring billions despite public skepticism; and renewed international support and engagement, underpinned by phenomenal diplomatic breakthroughs. For example, a single gesture of support from Qatar for Syria’s gas supplies is equivalent to nearly a third of the aid provided to Syria throughout 2024, as tracked by UNOCHA.

Government outreach has attracted substantial global interest. Investment forums have been held, resulting in the signing of dozens of MoUs that will translate to economic growth going forward. In our mapping of all MoUs in various issues of Syria in Figures (Article 1, Article 2, Article 3), we highlight that 67.5% of signatory companies are low risk: legitimate, legally registered, with a record of successful project implementation and, most importantly, often state-backed—primarily by Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Assuming that just 20% of announced MoUs—totaling USD 25.9 billion—materialize as investment over the next five years, this would amount to USD 5.2 billion. That figure alone is equivalent to roughly 20% of Syria’s estimated GDP of USD 20 billion (2022), even before accounting for any multiplier effects.

The government has also demonstrated an ability to implement swift policy decisions under difficult circumstances. The unification of tariffs across previously fragmented control areas and the long-overdue unification of exchange rates (see our article on the exchange rate) are not administrative tweaks but substantive policy shifts. The resulting confidence effects have been tangible. Prices declined for much of the post-transition period. Even as inflation has re-emerged over the past two to three months, price increases remain far less severe than in previous years.

The Bad

That some MoUs will fail to materialize is neither surprising nor uniquely Syrian. By definition, MoUs are expressions of intent rather than binding commitments, and many evaporate once feasibility studies, financing structures, and political realities collide. The problem is not that some projects will never see the light of day, but that a number were never credible to begin with. The frequently cited Saudi-funded Damascus metro project is a case in point. Even assuming tunneling does not run headlong into the dense archaeological layers of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city, the underlying economics remain implausible. A viable cost-recovery model—let alone a profitable one—would require demand that simply does not exist.

More troubling than unrealistic projects is the process by which MoUs are nominated, evaluated, and approved. The current approach appears ad hoc and opaque, with little evidence of standardized feasibility screening or competitive selection. This has inevitably fueled concerns about cronyism and preferential access, particularly in high-profile cases such as the largest MoU announced to date involving UCC Holding. Even if no impropriety ultimately exists, the absence of transparent criteria and publicly available documentation creates perception risks that Syria can ill afford at this stage of re-engagement.

This lack of discipline at the project level reflects a broader absence of a coherent reconstruction roadmap. What are the government’s priorities? How are they to be sequenced, and how will they be funded? Large commercial infrastructure projects can, of course, boost headline growth. But they are not necessarily what Syrians need most, as their benefits often accrue to only a few. It remains unclear how the authorities intend to finance essential, non-commercial infrastructure—such as basic public works—that generate high public and social returns but little or no profit while planning for tax cuts that are likely to limit the state’s revenues considerably. These are precisely the investments that international businessmen, whom the government is actively courting, are least likely to fund without clarity on who pays for what, through which instruments. As a result, reconstruction is becoming skewed toward what is marketable rather than what is necessary.

The lack of vision on specific initiatives or sectors may be understandable, given the heavy inheritance from the Assad regime. More consequential, however, is the declining clarity at the strategic level. In the immediate aftermath of Assad’s toppling, the overarching economic direction—whether one agreed with it or not—was clearer. The Caretaker Government spoke openly and consistently about privatization, trade liberalization, and a reduced role for the state in large segments of the economy. Those signals mattered: they gave investors a sense of direction and allowed markets to form expectations. Yet the Interim Government, which assumed office in April, has since muddied the picture.

Public statements on core economic questions—particularly privatization and subsidies—have become contradictory, varying not only across ministries but at times within the same institution. In some cases, officials have signaled a commitment to market-oriented reforms while, in practice, the government has maintained state control by intervening in private sector affairs, monitoring prices, or restricting trade.

The Ugly

One of the most concerning developments in post-Assad Syria has been the rapid concentration of authority within the presidency, despite gains in the agility of economic policymaking. The Constitutional Declaration concentrated extensive powers in the executive branch while remaining notably vague on the roles and checks of both the legislature and the judiciary. Although the document is explicitly provisional, there is no visible roadmap toward a permanent constitutional framework, particularly in light of the continued delay in forming a parliament. Presidential decrees now span virtually all domains of public life, from core legislation and amendments to senior appointments across the state apparatus.

This centralization is further entrenched through the institutional architecture. Key bodies responsible for managing the country’s reconstruction and economic recovery—such as the Syrian Sovereign Fund, the Syrian Development Fund, and the restructured Syrian Investment Agency—are all governed by boards appointed by presidential decree and report to the Supreme Council for Economic Development, a body created and chaired by the President. In effect, strategic economic decision-making has been consolidated within a narrow executive circle, often sidelining government ministers, with little to no formal oversight. Given that reconstruction costs are estimated to exceed USD 200 billion, this degree of concentration heightens the risk of reemerging rent-seeking and cronyism.

Additionally, accountability thrives on transparency—an area where several of these institutions fall short. The Syrian Sovereign Fund illustrates this challenge. While its formal mandate and funding sources are defined in a presidential decree, the Fund is also receiving assets seized from businessmen and entities accused of having accumulated wealth illicitly under the Assad regime. This function is not codified, leaving the legal basis for such seizures ambiguous. As a result, asset confiscation risks being applied selectively, creating space for harassment or political targeting.

Compounding this opacity, there is no publicly available reconstruction or asset-management strategy clarifying how the Fund’s resources are to be deployed, nor has the head of the Fund been appointed through a transparent process.

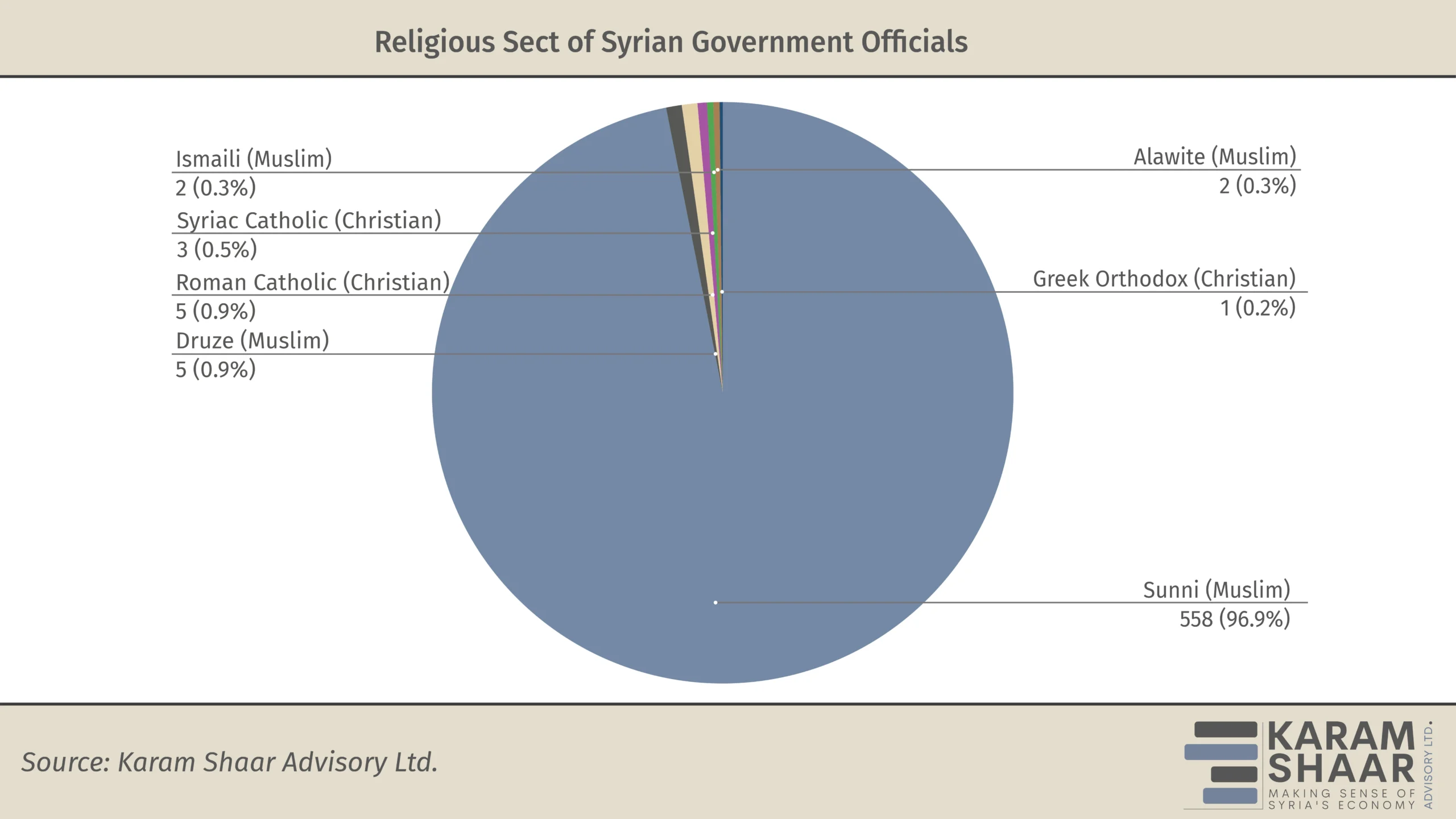

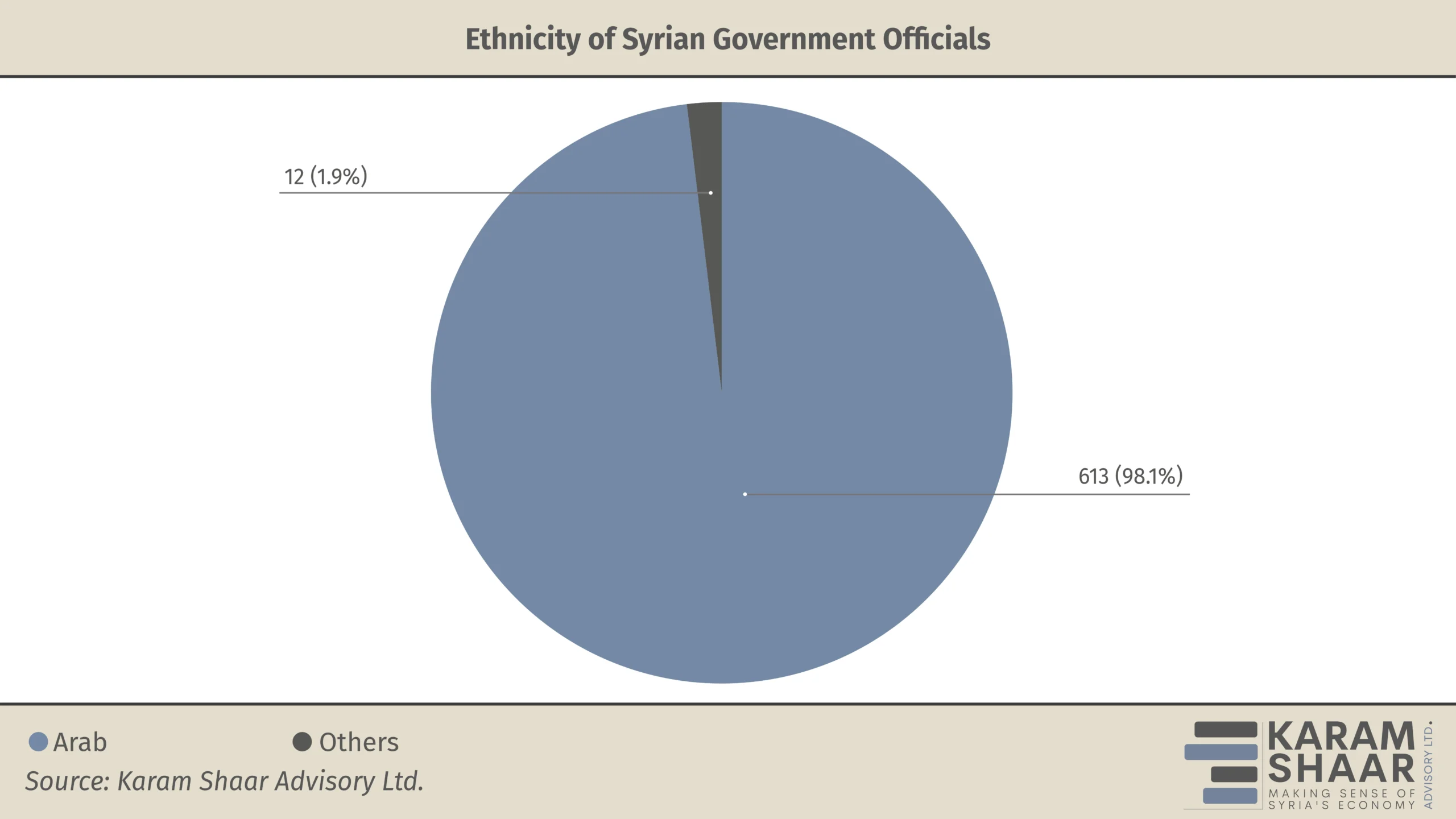

The most worrying development since Assad’s downfall, however, is the lack of inclusive governance. Since the formation of the Interim Government on 30 March 2025, our Advisory has tracked the appointment of 626 senior officials, including ministers, deputy ministers, ministerial advisers, heads of public institutions, investigative committees, the High Commission for Elections, and the leaderships of chambers of commerce and industry. The resulting profile of the governing elite is exceptionally homogeneous: virtually all are Sunni, Arab, and male.

Homogeneity at the very top is not, in itself, unusual—even in democratic contexts. However, in functional political systems, inclusivity is typically restored at lower levels through consultation, institutionalized feedback loops, and meaningful engagement with civil society and technocrats. To date, this has been limited. Instead, early reforms point to a pattern of rapid, top-down decision-making pursued with minimal consultation and weak institutional mediation. This matters not only from a moral standpoint, but from policy-quality and security perspectives: groups most affected by economic policies are also the most capable of identifying viable solutions. For instance, women are key actors in post-conflict settings and, especially as they experience inferior socioeconomic conditions, are often better placed to identify constraints and trade-offs that men are more likely to overlook. Alawites, who are extremely under-represented, are likewise best positioned to identify suitable economic interventions for their struggling regions.

The marginalization of social groups, technocratic input, and private-sector representatives risks eroding the transition’s legitimacy, exacerbating horizontal inequalities, and reactivating the well-documented “conflict trap” that has historically haunted post-war recoveries. By narrowing participation in decision-making, Syria risks governing with an incomplete understanding of its own economy and society.

A Word of Advice

Syria’s prospects are strongly contingent on state performance, with state failure likely to plunge the country back into conflict. Combined with the generally receptive attitude of government officials to advice, supporting state institutions should be a priority for those who support and oppose the political leadership alike. This becomes clear when one observes how little capacity exists within public institutions, underscoring both the scale of the challenge facing government officials and the need to support them wherever possible.